The spread of Angiostrongylus vasorum across the UK in recent years alongside drug companies having products licensed for its treatment and prevention, has led to raised awareness of this parasite among veterinary professionals and the public alike. This raised profile has been beneficial in reducing canine morbidity and mortality associated with infection, especially in parts of the country where it has not previously been endemic or routinely diagnosed. Veterinary nurses play a key role in giving accurate risk-based parasite prevention advice to clients. When advising clients on the need for angistrongylosis prevention as part of an overall parasite control programme, nurses need to consider the factors driving spread of the parasite and the resulting geographic and lifestyle factors likely to increase exposure risk.

Foxes act as a wildlife reservoir host for A. vasorum worms in the UK but any canid can be infected including domestic dogs. First stage larvae (L1) pass out in the faeces and require gastropod molluscs (slugs and snails) as intermediate hosts for further development. Infection occurs in canids when infective third stage larvae (L3) are ingested. This occurs most commonly through deliberate or accidental consumption of infected slugs or snails (Morgan et al, 2005) or paratenic hosts such as amphibians and possibly birds. Infection has also been demonstrated under experimental conditions to occur from ingestion of larvae present in slime trails (Conboy et al, 2015), but the effect of this in natural transmission is unlikely to be significant. Infected slugs have been found to contain between 1 and 54 L3 larvae, with less than 1% of these larvae leaving live slugs (Lange et al, 2018).

The most common clinical presentation in infected dogs is mild to moderate pulmonary signs. The most significant of these are coughs (either productive or unproductive), and dyspnoea, with or without tachypnoea. A less common but more severe consequence of infection is a varying degree of coagulopathy (Morgan et al, 2005). The mechanism of this aspect of infection is still poorly understood but can lead to potentially life-threatening signs including anaemia, haematomas, neuropathies, increased and prolonged post-operative bleeding and post traumatic haemorrhage. Cardiac signs are relatively rare with pulmonary hypertension occurring in less than 5% of dogs infected with A. vasorum in primary practice (Koch and Willesen, 2009). Although less common, these more severe signs can occur even if the parasite is present in low numbers.

Factors driving spread and geographic risk

A. vasorum has spread rapidly over the past 20 years from endemic foci in Wales, the South West and South East of England across the whole of the UK. Increased reporting of cases has been seen in domestic dogs, with 20% of practices across the country having seen at least one case over a 12 month period (Kirk et al, 2014). This increase in range and number of cases had occurred in the face of increased awareness and publicity so it was initially unclear whether increased reporting may be distorting true infection and disease incidence figures. To establish if this perceived spread and increasing number of cases was genuine, post-mortem surveys were carried out on foxes in 2005 (Morgan et al, 2008) and in 2014 (Taylor et al, 2015) which act as wildlife reservoirs. The over-all prevalence rose from 7 to 18% in foxes during this period and extended to regions previously clear of infection such as Northern England and Scotland. The spread of A. vasorum is therefore genuine but not uniform, with focal areas of very high prevalence and other areas remaining free of infection. Case reporting sites by Idexx and Bayer have been useful in mapping areas of high prevalence and the introduction of A. vasorum into new areas. Reporting of cases is only voluntary however, and distribution of infection very fluid with new foci forming. It is likely that a variety of factors are driving the spread of A. vasorum to new areas of the country and allowing it to establish. These include:

- Climate: it has been suggested that a warmer milder climate has created favourable conditions across the country for A. vasorum to spread. While this may explain expanding distributions in the UK, it is unlikely to be a major driver of spread in the UK, where the climate has long been favourable for A. vasorum establishment (Morgan et al, 2005). It may have an indirect effect though in allowing a longer season of slug and snail activity and allowing them to be active for longer periods of the day. This may increase the odds of a domestic dog encountering an infected gastropod (Aziz et al, 2016).

- Fox populations: increasing fox populations have also been suggested as a possible cause of A. vasorum spread. This is unlikely as the UK has maintained large fox populations for decades and individual foxes to do not travel sufficiently far to explain the long distance focal spread of A. vasorum across the country. The increased urbanisation of the red fox in some British towns and cities, however, may be bringing the parasite into closer proximity with dogs.

- Slug and snail populations: the UK has always enjoyed among the largest numbers of slugs in Europe and therefore, slug and snail numbers are unlikely to have an impact on A. vasorum distribution. Movement of horticultural products around the country containing infected slugs and snails, however, may have introduced infection to new areas.

- Movement of dogs: where foxes do not move large distances across the UK, dogs do on a frequent basis. The focal spread of A. vasorum with long geographic ‘hops’ to new areas means that long distance movement of the parasite is required and likely therefore that infected domestic dogs are involved.

The focal and unpredictable movement of A. vasorum to new areas of the country makes prevention advice based on geographic risk dependent on knowledge of whether cases of angiostrongylosis are occurring locally. Some parts of the UK, such as greater London, are highly endemic for the parasite and prevention of canine angiostrongylosis is essential. Whether routine prevention is required elsewhere requires screening of dogs with relevant clinical signs and alerting other practices and members of the public when cases are identified. Useful screening tests for A. vasorum infection in clinically affected dogs include:

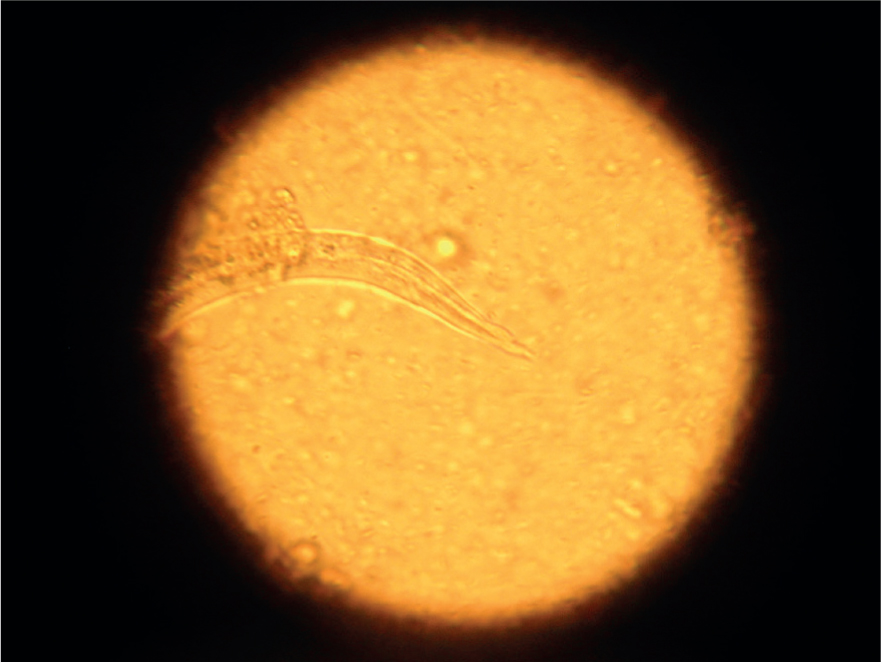

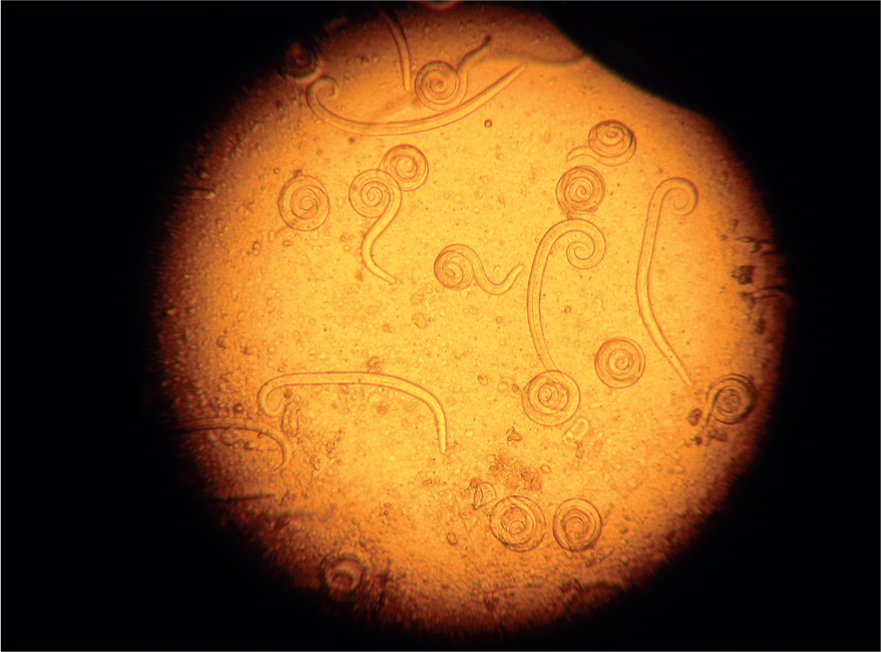

- Baermann faecal analysis (Figure 1): The gold standard for the diagnosis of A. vasorum L1 larvae in faeces. In experienced hands this test is highly specific, but sensitivity of the test relies on the faecal sample collected. Larvae are only shed intermittently in the faeces and if faeces are left on the ground, they will rapidly be contaminated by free living nematodes from the environment (Figure 2). To maximise sensitivity, faeces must therefore be collected fresh and collected over 3 consecutive days. The test has the advantage of being able to also diagnose Filaroides (Oslerus) osleri and Crenosoma vulpis infection as L1 larvae of these parasites are shed in the faeces in a similar way. These can be identified by morphological differences summarised in Table 1 but can be easily misidentified or confused with free living nematodes. Specificity, therefore, improves with experience. Nurses performing Baermann analysis on a regular basis can perform a useful in-house screening and diagnostic role for a range of lungworms if time and space in practice allow

- Faecal smear: a useful initial screening test which is quick to perform, cheap, can be carried out in house by nurses and yields rapid results. It has a poor sensitivity of 54–61% and so further tests should be carried out if the result is negative but clinical lungworm infection is still suspected (Humm and Adamantos, 2010).

- AngioDetect™ (Idexx Laboratories): a point-of-care blood test which detects circulating A. vasorum antigen in the blood. It has a reported sensitivity of 84.6% and specificity approaching 100% (Schnyder et al, 2014). This test allows for more rapid diagnosis in a clinical setting and also allows many dogs with clinical signs compatible with A. vasorum infection to be tested relatively economically and rapidly. This in turn allows a picture within practices to be built up as to whether A. vasorum is present in the local area. This picture needs to constantly updated however as the regional prevalence of A. vasorum can be very fluid. It has the drawback of only detecting A. vasorum, and so other lungworm infections must still be considered.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage: often yields larvae in infected dogs but may carry some risk in dogs suffering from respiratory compromise.

Table 1. Morphological characteristics allowing differentiation between L1 lungworm larval stages in the faeces

| Lungworm | Length | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|---|

| Angiostrongylus vasorum | 334–380 µm | Tail has a dorsal notch (Figure 3) and larvae are often coiled (Figure 4). |

| Crenosoma vulpis | 243–281 µm | Tail is straight and pointed and larvae straighter in faecal samples, rarely coiled. |

| Oslerus osleri | 229–251 µm | Notch in tail after which the distal end has a wavy appearance. |

There is no legal obligation to report cases of A. vasorum so highlighting cases seen in practice is important to raise awareness of local presence of the parasite. Notification of positive A. vasorum cases having been identified in a practice should be shared on practice websites and social media pages to alert other practices and dog owners to the presence of a parasite in a local area. Veterinary nurses often play a key role in veterinary practice social media communication and therefore can promote awareness of local cases in a responsible way via established contacts and media channels. This will help to inform whether preventative treatment for angiostrongylosis in local dog populations is required. In addition to geographic risk, lifestyle factors also need to be taken into account when assessing risk. Recording cases on case reporting map sites will also help to build a picture of A. vasorum distribution nationally.

Lifestyle risk factors

Dog lifestyle factors are also likely to increase the risk of exposure to the parasite. These include:

- Serial slug and snail consumption: some dogs are attracted to slugs and snails and deliberately consume them, putting them at greater risk of becoming infected with A. vasorum

- Grass consumption and coprophagia: some slugs are coprophagic, putting them at risk of being consumed by coprophagic dogs. Some slug species are also very small (Figure 5), increasing the likelihood of accidental ingestion by dogs (Aziz et al, 2016).

- Drinking from puddles and other still water outdoor water sources: large numbers of larvae are released from slugs that die in water. This may potentially increase the risk of exposure for dogs that like to drink from still, shallow outdoor water sources.

Preventative treatment for angiostrongylosis should be considered in dogs that regularly engage in these activities.

Control

A number of control strategies for A. vasorum infection in dogs other than the use of monthly preventative anthelmintic treatments have been considered and are summarised in Table 2. Measures such as responsible disposal of dog faeces, avoiding walking dogs after heavy rainfall and during humid conditions when slugs are likely to be active and bringing outdoor dog toys and water bowls inside when not in use, are useful in reducing slug and snail exposure. They are unlikely to completely prevent exposure however, making routine preventative treatment essential in at risk dogs. Use of a licensed monthly moxidectin or milbemycin oxime prophylactic preparation will greatly reduce the risk of disease in at-risk dogs. All of these preventative products are currently POM-V, but nurses play an important role in assessing whether they are required. Discussions at reception and a range of nurse clinics such as flea and parasite control consultations, puppy checks and parties are all opportunities to obtain information and assess risk.

Table 2. Possible methods for Angiostrongylus vasorum control other than chemoprophylaxis

| Method | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Eradication | Impractical due to intermediate host and wildlife reservoir. Use of molluscicides may increase risk of exposure due to exposure to dead slugs and snails |

| Reduction of exposure to intermediate host | Difficult due to ubiquitous nature of gastropod intermediate hosts. Some slugs on grass are very small |

| Use of nematophagous fungi | Predate L1 larvae but are currently not commercially available |

| Picking up of dog faeces | Important and may have local impact but of limited use in A. vasorum control due to wildlife reservoirs |

There are differences in license claims with moxidectin/imidacloprid spot-on solutions having a claim to eliminate infection and other products having a claim to reduce infection and prevent clinical disease. There is currently no evidence this has any significant effect on larval shedding or disease prevention in the field, so while it is a factor in product decision making, it should only be considered as one component alongside owner compliance and preference for a tablet/spot-on and how a product fits into an overall parasite control programme. Other parasite prevention needs such as tick, roundworm and tapeworm prevention should also be considered.

Conclusions

A. vasorum has spread across the UK but not in a uniform fashion, making awareness of whether it is present in local areas vital in assessing risk to domestic dogs. A. vasorum infection needs to be considered in dogs presenting with respiratory signs, coagulopathies, neuropathies and pulmonary hypertension. Screening or prevention prior to surgery is also vital in endemic areas. Tests such as direct faecal smears and Angiodetect™ provide the means to rapidly screen suspected clinical cases and build up a picture of whether A. vasorum is present in a particular area. While obtaining, recording and sharing these data is vital to help map the distribution of A. vasorum in domestic dogs, the fluid nature of endemic foci must be remembered and veterinary professionals must not become complacent if they have not yet seen cases in their locale. The sensitivities of tests need to be considered when using them and a negative result does not rule out the possibility of infection. Lifestyle factors are important when considering whether dogs require preventative treatments and if so, which one might be suitable for an individual client. Nurses play a vital role in gathering this information and using it to give accurate risk-based preventative advice to clients.

KEY POINTS

- Angiostrongylus vasorum has spread across the UK with endemic foci present across the country.

- It is is potentially highly pathogenic and capable of causing a wide range of clinical presentations. In addition to respiratory disease, these include coagulopathies and neuropathies.

- Screening dogs with these relevant clinical signs will help to establish if A. vasorum is locally endemic.

- This in combination with the rapid spread of A.vasorum across the country means that veterinary professionals need to consider preventative treatment for A. vasorum in at risk dogs.

- Factors to consider when assessing if dogs are at increased risk from A. vasorum infection include lifestyle and geographical location in relation to recorded cases.