This article aims to provide the reader with the necessary understanding and information to produce diagnostic orthopaedic radiographs. The results of a good radiographic examination can provide definitive information for diagnosis.

A diagnostic radiograph is one that maximizes the amount of information available from the resulting radiograph, enabling the radiologist or clinician to make a diagnosis and when necessary compare it with text book ‘normals’ and anatomical specimens.

In order to produce diagnostic radiographs it is important to use a standard technique; this involves looking at all aspects affecting the production of the radiograph.

The animal

Preparation

Animals are not uniform shapes and sizes and this needs to be taken into consideration when planning the radiographic examination. Orthopaedic cases may also present with various types of external device (fixators, dressings, casts etc), which may require some imaginative positioning and exposures to get the views required.

Before starting the radiographic examination adequate preparation of the animal should be undertaken. The coat should be clean and dry as a dirty and/or wet coat can cause radiographic artefacts (Dennis et al, 2010). Where possible dressings should be removed or reduced to a minimum taking the necessary infection control measures. Similarly collars and harnesses should be removed as they may overlie the area of interest.

Restraint

Adequate restraint is necessary to achieve the various views required in orthopaedic radiographic studies. Some views require the use of ties, e.g. stressed views of the carpus/tarsus etc, and in these cases general anaesthesia is required. The orthopaedic case can often be painful on presentation and therefore adequate analgesia and restraint (sedation or general anaesthesia) will be necessary. Sometimes for clinical reasons, e.g. dyspnoea, it may be necessary to radiograph the animal conscious. This requires time and patience, and will restrict the type of views possible, it will also increase the possibility of movement blur, but manual restraint must be avoided at all times, as stated in the Ionising Radiations Regulations 1999.

Positioning

Use standardized positioning – see orthopaedic technique.

The equipment

The X-ray generator, control panel, table and tube head.

Ideally they will have:

Cassettes and film screen combinations

Ideally there will be:

Grids

Use grids if the tissue depth is >10 cm, e.g. pelvis, shoulders. The Potter Bucky grid is the one of choice, it is easier to use and grid lines are avoided. If using a tabletop grid the pseudo focused type is the one of choice, it reduces scatter, but can be used for a range of FFDs (Figure 3).

Positioning aids and markers

Sandbags can be used to pull limbs forward, backward, away from the area of interest and to stabilize the patient. Ideally they will have removable covers for washing or be made of an easy clean material. They should be about two-thirds full to keep them flexible and of various sizes in width and length (Figure 4a).

Foam shapes are used to support areas and avoid limb/joint rotation. It is useful to have a variety of shapes and sizes including a mini set to use on cats and small dogs (Figure 4b). Wrapping in cling film is recommended as an infection control measure. The foam should be checked for radiolucency.

Radiolucent cradles can used to support the main body of the animal in conjunction with sandbags, e.g. ventrodorsal (VD) extended view of the hips/pelvis (Figure 4c).

Markers and ties can be used with either sandbags or table anchor points to fully extend limbs, and different types of left/right (L/R) markers used to identify which side/limb is being radiographed (Figure 4d).

The orthopaedic technique

The use of a standard technique will ensure the production of diagnostic quality radiographs (see the Step-by-step guide).

Nomenclature used

Radiographic projections are described in the direction the X-ray beam travels through the animal to the film. The most commonly used projections in orthopaedic radiography are given in Table 1. Other views can be taken, e.g. dorsal acetabular rim (DAR) and various stressed and oblique views, these should be named accordingly.

| Projection | Nomenclature | Area used |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral, mediolateral, or lateromedial | L, ML or LM | Appendicular skeleton |

| Dorsoventral or ventrodorsal | DV, or VD | Pelvis and spine |

| Craniocaudal or caudocranial | CrCd, or CaCr | Proximal forelimbs and hindlimbs |

| Dorsopalmar or palmarodorsal | DPa, or PaD | Forelimb, distal to and including the carpus |

| Dorsoplantar or plantarodorsal | DPl, or PlD | Hindlimb, distal to and including the tarsus |

Radiographic positioning

The shoulder joint

A standard examination of the shoulder joint requires two views mediolateral (ML) and caudocranial (CdCr), where tendon or muscle involvement is suspected then the skyline view is taken. Where depth of tissue is >10 cm, the ML and CdCr views should be taken using a medium speed cassette and a grid (Potter Bucky if possible). If <10 cm then use a slow speed cassette on the table top. General anaesthesia or sedation is required.

Shoulder joint — ML

Shoulder joint — CdCr

Shoulder joint — skyline (tangential)

The elbow joint

The elbow joint is complex and can be positioned in a number of ways to view all the structures radiographically. A slow film/screen combination should be used on the table top. General anaesthesia or sedation is required.

The British Veterinary Association (BVA)/Kennel Club run the elbow dysplasia scheme and score the elbows based on two ML views:

It is important in each view to avoid rotation. Full procedure notes for the scheme can be downloaded from the BVA website.

Elbow joint — ML

Elbow joint — craniocaudal (CrCd)

There are two ways of positioning for this radiographic view.

Dorsal recumbency — This method is good for examining condylar fractures.

Sternal recumbency — This method is useful when assessing deformities of the forelimb, especially in chondrodystrophic breeds, e.g. Basset hounds, the whole antebrachium should be included while still centring on the elbow.

Elbow joint — CdCr

This view is often preferred by clinicians when suspecting problems with the medial coronoid process or osteochondrosis of the medial condyle of the humerus; however the increased object film distance (OFD) will mean that the image is magnified.

The hips/pelvis

The standard view used for assessment of the hips/pelvis is the VD extended view. The BVA/Kennel Club run a hip dysplasia screening scheme using this projection; full procedure notes for the scheme can be downloaded from the BVA website.

A medium speed film/screen combination with a grid should be used except for very small dogs and cats where a slow film/screen combination is used on the table top. General anaesthesia or sedation is required.

Hips/pelvis — VD extended

Tip — it is advisable to maintain the animal in position while the radiograph is processed so that adjustments can be made if axial rotation has occurred. To correct axial rotation raise the hip on the side on which the obturator foramen is smaller. Often ensuring that the head/neck end of the dog is straight will correct rotation at the pelvis (Figure 11a and b).

The stifle joint

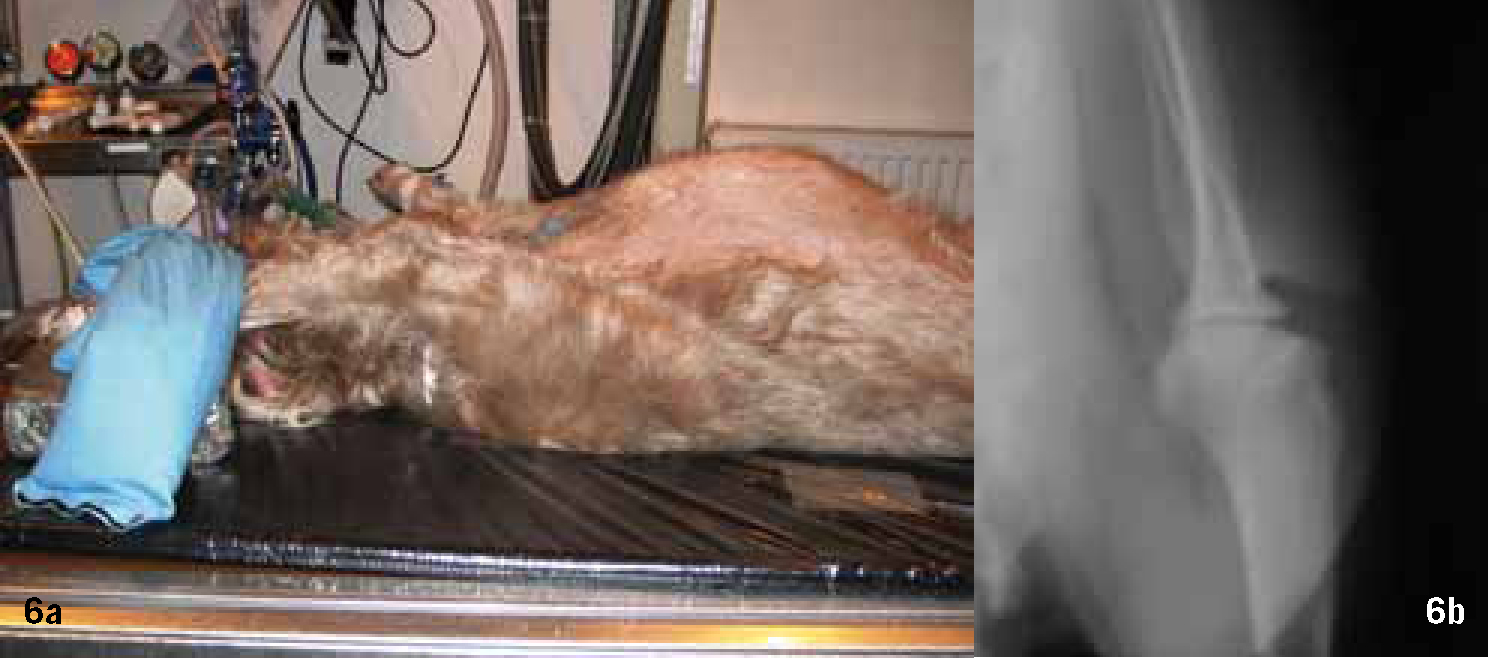

The most commonly used projections for the stifle joint and associated structures are the ML and the CdCr. If cranial cruciate rupture is suspected then the hock is included. A slow film/screen cassette combination should be used on the table top. General anaesthesia or sedation is required.

Stifle joint — ML

Tip — if the animal has well developed musculature on the hind limbs, e.g. Staffordshire Bull terriers, it may be easier to draw and secure the limb cranially or place a foam wedge under the hip (Figure 12a and b).

Stifle joint — CdCr

Tip — Moving the tail to the side of the affected limb will aid positioning and avoid medial rotation.

Conclusion

The production of diagnostic orthopaedic radiographs is challenging, but using a standardized technique and following the basic principles outlined above can be very rewarding.