People and pets are under-treated for pain at the end of their lives (Meier, 2003; Villalobos and Kaplan, 2007). Pain is one of the most important parameters to assess in animals with regards to their welfare and wellbeing, but unfortunately it is also one of the most difficult parameters to assess. Pain is often not considered, recognised, and overlooked by owners and veterinary professionals alike. For many reasons, pain management in animals is generally inadequate (Flecknell, 2008). The reason why pain is often not considered, not recognised, overlooked and under-treated is multi-factorial. An overview of this (in a veterinary context) can be found in Bradbury and Morton (2017), and Simon et al (2017).

There is a difference between not considering and not recognising pain. There are multiple reasons why pain is not considered; for example because of sociological, cultural and gender differences. The ability to consider pain is often linked to empathy. Empathy cannot be taught, only facilitated. The ability to recognise pain is a skill that can be taught.

Acute pain and chronic pain are different clinical entities. Acute pain is short lasting, serves a biological purpose, is caused by a specific injury or disease, and is self-limiting (it exists within the expected time of healing). Chronic pain has multiple etiologies (Grubb, 2010). It often outlasts the time associated with healing, can arise from a psychological state, and has no purpose or end point (Grichnik and Ferrante, 1991; Epstein et al, 2015).

Pain that has not been managed can lead to persistent pain states, such as allodynia and central sensitisation, or ‘wind up’. Patients can also present with ‘acute on chronic’ pain. For example, this can occur in an animal which already has chronic or unmanaged osteoarthritic or neuropathic pain, and then further acutely deteriorates.

Chronic pain is grossly under-diagnosed and under-treated in humans and animals (Bell et al, 2014; Simon et al, 2017).

This article aims to look at some common end-of-life conditions that cause (or have the potential to cause) pain in veterinary patients, and provides basic information on how to manage this in practice.

Who is an end-of-life patient?

Contrary to what might be assumed, actually any patient coming in to the veterinary clinic could be an end-of-life patient. A ‘healthy’ dog with behavioural issues, or two young feline companions euthanased because the owners were emigrating, were all end-of-life patients. A 14-year-old greyhound with an osteosarcoma and a pathological fracture undergoing amputation was an end-of-life patient that died in hospital, 2 days after never really recovering from amputation surgery.

Therefore, whether a patient is at the end-of-life depends as much on the owner's intentions and decision, and the veterinary surgeons' intentions and decision, as it does on natural ageing and disease course. However, as veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses, we should accept now that for pets with a normal lifespan there is a fifth life stage after ‘geriatric’ — ‘end-of-life’.

End-of-life can also occur at any point during the pet's lifetime.

Why is pain management in end-of-life patients important?

There could be two different ways of looking at this:

- Pain management is always important. Managing pain at the end-of-life is no more important than managing pain in any other life stage, in any other painful condition. It is just another experience the animal is having.

- Pain management is far more important at the end-of-life, because it is the last experience the animal will ever have. There are no more experiences after this. The pet's end-of-life experience will also be unforgettable to the carers. Therefore, uncontrolled pain, whether chronic and ongoing or acute, should not overshadow this last experience.

When thinking about end-of-life experiences and euthanasia, it is perhaps easier for us (and clients) to imagine what we would want for our own end-of-life experience, and then imagine what our pets would want. As most would appreciate, many owners believe they may know what is best for their pet, but equally some owners do not. As veterinary professionals, we might also not know what is best for that individual end-of-life animal — until we explore and gather more information. Therefore, the resources, articles and CPD available on veterinary end-of-life care and palliation that are available, are extremely useful tools in managing end-of-life patients (see the resources at the International Association for Animal Hospice and Palliative Care). The perspective is, as much as possible, patient (and care-giver) –centric; also called bond-centred care.

Why is pain management in end-of-life patients overlooked?

Pain in any animal can easily be not considered, not recognised, and overlooked. In the end-of-life animal, there are further challenges:

- Tradition and habits

- Peoples' perception and ignorance (‘he is just old’)

- Inherent cultural and societal values relating to how we treat people at this stage in their life

- Traditional or historical foundation of veterinary (and human) medicine in ‘fixing’ and ‘curing’ and ‘getting the patient to live as long as possible’ — rather than helping them to die

- Difficulty in assessment

- It is very difficult to assess pain in animals, as it is often subjective and qualitative. Human competency at pain assessment, or willingness to consider pain in an animal, depends on the species being assessed

- People may assume that the specific behaviours their pet is showing are because he/she is ‘just getting old’; when in actual fact, the behaviours are related to pain

- Reduced cognitive function, cognitive dysfunction, or reduced consciousness in severely ill or comatose animals makes pain assessment very challenging

- De-prioritisation

- End-of-life patients are often elderly and may have multiple conditions and co-morbidities. Focusing and medicating on other disease processes can lead to pain being overlooked.

Is the main problem the most common one?

Research by Dan O'Neill and colleagues at the Royal Veterinary College (RVC) looked at common problems in UK companion cats and dogs. They studied data from first opinion veterinary practices (predominantly in the south and south east). By assessing the frequency, duration and severity of the presenting problems, a welfare impact score (on a population level) was created. The problems with the highest scores were: dental disease, osteoarthritis (OA), and obesity (O'Neill et al, 2018).

Human behaviour and ignorance causes people to normalise problems that are very common, so that it becomes acceptable. Examples of this are:

‘He is fine, but we only feed him wet food because his teeth are bad.’

‘It takes her a while to get up, but she is fine once she gets going’.

It is estimated that around 30% of pet dogs and cats seen by veterinary surgeons are classified as ‘senior’, and this population is likely to have a high prevalence of chronic pain (Matthews et al, 2014). It is likely that conditions such as dental disease, OA and obesity are also common end-of-life conditions. Potentially, these may be reasons why, or part of a decision why, an animal may be euthanased.

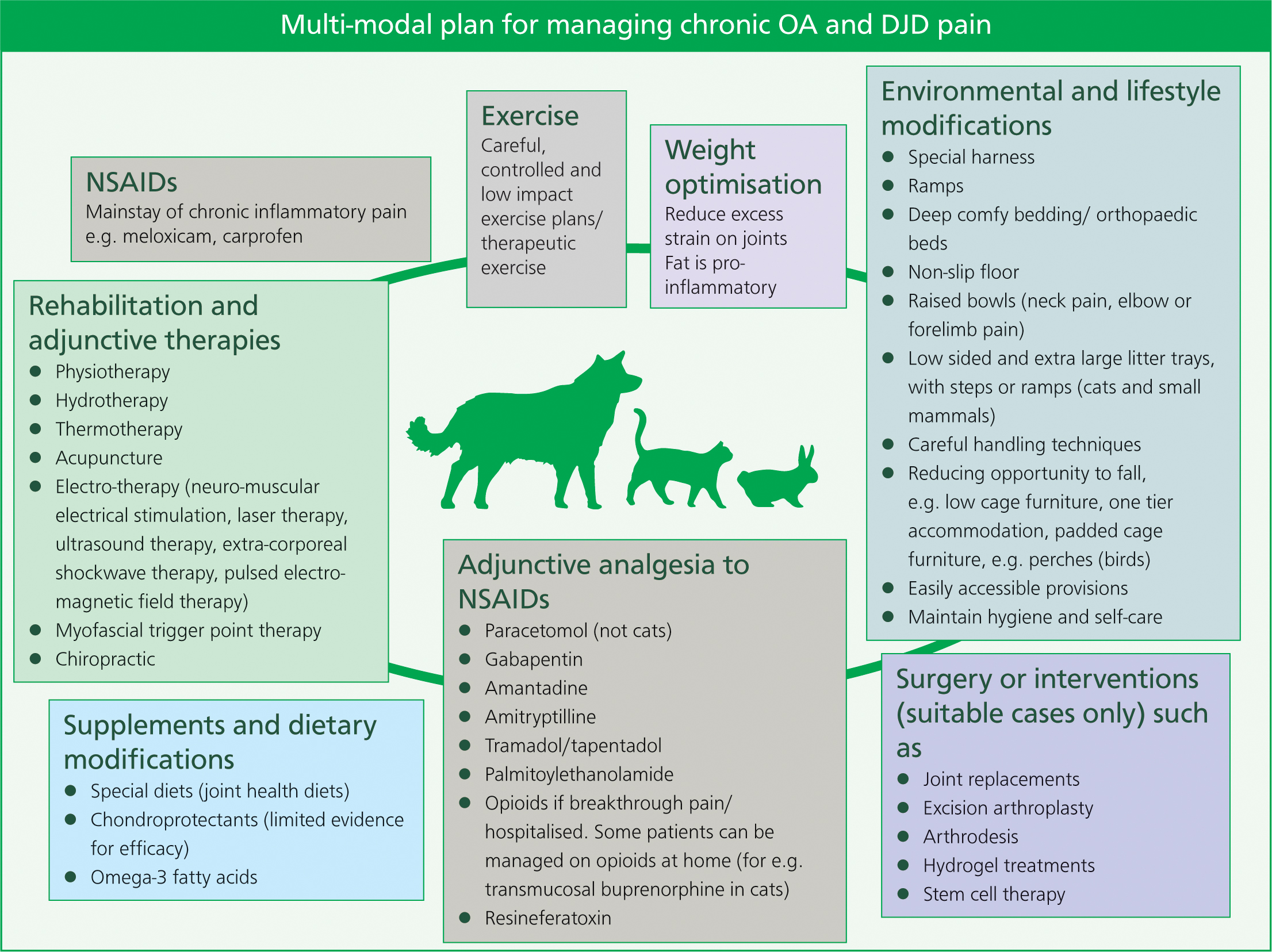

Therefore, the aim of this article is to look at pain management in dental disease, OA and degenerative joint disease (DJD) — and substituting obesity with cancer — as a common and potentially (most often) painful end-of-life condition. Most research on this subject has been on dogs and cats. However, with careful species-specific consideration and research, many of the same principles used with cats and dogs, along with some different ones, can be (and are) applied to other species (Figure 1).

OA and DJD

OA and DJD are significant and underdiagnosed diseases in the ageing companion animal population (Epstein et al, 2015). DJD is a degenerative change in any synovial, cartilagenous or fibrous articulation in the skeleton. OA is a pathological change of a diarthrodial synovial articulation (Robertson, 2008).

Assessment of pain in OA and DJD in dogs is well researched. See Walsh (2016) and Goldberg (2017a,b) for a thorough account of chronic pain in cats and dogs. For objective scoring systems that can be used as monitoring tools for improvement or decline, see the chronic pain scales Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs (LOAD) (https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/bitstream/10174/19611/2/liverpool%20OA%20in%20dogs%20-%20load.pdf) and Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index (https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?type=supplementary&id=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0131839.s001), which can be used in canine and feline musculoskeletal pain respectively.

A lot can be done for OA and DJD

See the multi-modal plan for managing OA and DJD pain (Figure 2).

Nursing considerations

Unfortunately, it is still a prevalent tradition among veterinary professionals to withhold analgesia due to the fear of side-effects (Bradbury and Morton, 2017; Simon et al, 2017). Analgesia should never be withheld due to fear of side-effects, because relief of pain is a welfare priority.

A long-standing but recently changing example has been the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in elderly cats. Researchers have studied the use of meloxicam in cats with concurrent renal failure and OA. Long-term treatment with oral meloxicam does not reduce the lifespan of cats with stable and pre-existent renal disease (Gowan et al, 2011, 2012). Analgesia is a requirement in painful animals for quality of life purposes, whether a patient has a concurrent organ failure disease or not.

Another example where analgesia is with-held due to unnecessary concern over side effects, is the irrelevant fear of ‘respiratory depression’ with opioids: this is still, unfortunately, a well-maintained veterinary myth (Wagner et al, 2003).

In a painful animal, using the excuse of ‘respiratory depression’ is no longer a reason to withhold opioid pain relief (Wagner et al, 2003).

It is generally considered now, that addressing the patient's present pain and quality of life is more important than any potential or future impacts of medication. If side-effects are a legitimate concern, there are always other analgesic options to consider.

To date, the greatest weight of evidence for efficacy of managing OA and DJD in dogs includes: weight management; NSAIDs; dietary optimisation; and exercise (Matthews et al, 2014).

In ageing animals, animals with OA or DJD, or where there has been a musculoskeletal injury or surgery, muscles become weaker, blood flow and elasticity decreases, and joints become less flexible. Weak or abnormal gaits may be due to muscle wasting, acquired neuropathies, functional problems, pain, or a combination of these factors. Physical therapies are an important (and often in humans, first line) management tool. Myofascial pain (for example, muscle knots, muscle tension, pain in connective tissues) is a physical problem; it is generally unaffected by analgesia, and should be treated with physical modalities (physiotherapy, acupuncture, myofascial trigger point therapy, massage) (Hunt, 2018) (Figure 3).

Hot and cold therapy, massage, range of movements, and short periods of active or assisted therapeutic exercise are essential to a pain management plan. This is not just for dogs; all animals benefit from physical rehabilitation, and can be successful with careful species-specific and individual consideration. For instance, sessions with cats work well if the sessions are kept short, the therapists ensure the cat enjoys and maintains interest in the session, and has a sense of choice and control. Cats can be willing physiotherapy and hydrotherapy participants if ‘asked correctly’ (Goldberg, 2016). Physical rehabilitation has been described, in varying capacities, in exotics and zoo animals, ranging from the laboratory mouse to the zoo elephant. Zoo animal rehabilitation can be added into a behavioural training programme, and many of these patients will undergo rehabilitation techniques voluntarily, or in return for positive reinforcement (Goldberg, 2019).

An extra point to consider is how to handle the arthritic patient in hospital. Careless positioning, pulling of limbs, or roughly moving patients between x-ray or theatre, in an animal that already has compromised joints, will be extremely detrimental when they wake up. Patients with OA and DJD under anaesthetic will need extra padding, for example using towels to provide support to the splayed hindlimbs and hips to a patient in dorsal recumbency on a theatre table. If they are on their side, the nurse should ensure that the uppermost limbs are parallel with the rest of the body by being supported underneath, and not hanging down or digging into a hard table edge, which could potentially cause muscle strain, aches or numbness.

These patients benefit from being cared for in the same way as for a recumbent patient. They should have the option of a padded bed, plenty of blankets for comfort and support, the option of a warm area to lie in, ensuring there is nowhere they can get ‘stuck’ in their kennel if mobility is compromised (Figure 4). Rubber matting inside and outside of the kennel, or non-slip ward flooring is ideal. These patients may need repositioning if they stay in the same position for a long time, short frequent bouts of manageable exercise, and the application of towel-covered hot water bottles to painful or restricted joints. Some patients will benefit from raised bowls and steps down from their kennel to the floor, and assistance to get up and down. Close attention should be paid to their hygiene. Most (if not all) of these considerations apply to all arthritic patients, regardless of the species (Figure 4).

Certain care aspects may differ slightly if the patient is post-surgery or post-injury. Physiotherapy or assisted exercise may begin after the patient has fully recovered, and cold therapy would normally be chosen for the immediate postoperative or post-injury period (24–72 hours). Thermotherapy is generally advised to be used for a maximum of 20 minutes per session, depending on the type used (Goldberg and Tomlinson, 2018).

Pain is a differential in any animal presenting with an inability to self-care or maintain their own hygiene; for instance, a matted coat, or urine or faecal soiling (Figure 5).

If the diagnosis is pain, it is appropriate to treat the pain first. Once the patient has been given adequate analgesia, procedures such as clipping matts (conscious or under sedation), washing soiled areas, applying barrier creams, regular grooming, and ensuring hygiene is part of the care and management of a chronically painful animal, alongside effective analgesia and the other mentioned techniques.

There is a range of equipment that can be used to help varying degrees of mobility issues in the small animal patient, particularly dogs and cats. These range from special harnesses, boots, slings, wagons, and ramps, to mechanical hoists.

If the problem is long-term, the aim is to provide a normal or as good a life as possible, with discomfort and stress minimised. If the patient is undergoing short-term rehabilitation for surgery or injury, rehabilitation will ensure a smooth, efficient recovery which minimises discomfort. However, it is important that the owner is aware that some rehabilitation techniques are best carried on for the lifetime of the pet, as part of pain management.

It is helpful to remember the chronic pain patient may be anxious. There are many animal studies showing that anxiety and depression are concurrent with pain states (Blackburn-Munro and Blackburn-Munro, 2001; Zhuo, 2016). It is important to take this into consideration and remember that all of the rehabilitation techniques, if used correctly in accordance to their ability and alongside an effective analgesia plan, will help them to regain their confidence.

For good tips and advice on how to provide care to a disabled patient at home, ranging from maintaining mental or psychological enrichment, how to teach owners to stimulate a disabled patient to toilet, through to advice on ‘caring for the carer,’ see Tomlinson and Waalke (2018).

Dental pain

Dental disease is a common health problem in small animal practice (Niemiec et al, n.d.).

Clinical signs of dental problems can start occurring in young cats and dogs and become very common in older animals. Due to the significant amount of pain and infection, including the local, regional and systemic consequences, dental disease can significantly decrease an animals' quality of life (Niemiec et al, n.d.; WSAVA dental guidelines).

‘Oral cavity diseases’ are the most frequently reported dis-orders in small herbivorous mammals, and when there is a genetic origin rather than husbandry related, the problems occur much earlier on in the lifetime of the pet (Verstraete and Osofsky, 2005).

Periodontal disease is a common husbandry-related problem in pet reptiles with acrodont dentition (such as in bearded dragons and chameleons) (Pollock, 2018). Oral stomatitis is a common husbandry-related problem in captive reptiles in general (Benato, 2010). Observant owners will pick up on behaviours associated with dental pain in reptiles, but unobservant owners will present with a very sick reptile that has not eaten for days, weeks or even months.

Dental disease is a relatively neglected area of veterinary medicine (Niemiec et al, n.d.). There is scarce original research on dental pain, and there are no dental pain scoring systems as yet. It is important to do an oral examination on pets regularly, and be aware that certain overlooked, unusual or subtle behaviours such as gradual food selectivity, a reduction in wanting to play with a certain toy or a game (such as tug), or a matted or unkempt coat in the case of cats and small mammals, may point towards dental pain. Polydipsia has been described in rabbits with dental pain. Some cases are very subtle and only picked up by observant carers; for example, Lewis (2017) described a police dog that would let go of the handler's arm prematurely during bite training.

There are very good lists of dental pain behaviours available, these can be found in the WSAVA dental guidelines (Niemiec et al, n.d.), DeForge (2009), March (2015), Mills (2016), and Lewis (2017).

It is clear from all of this information that dental pain is very unlikely to be shown outwardly in any obvious way, until the problem is severe — most animals will always choose to continue eating to ensure survival, until the problem is very bad; therefore dental problems can go unnoticed for a long time. Furthermore, dental problems are very difficult to spot in a brief conscious oral examination, particularly in small pet mammals and some reptiles (or in fact, in any patient that does not want their mouth examined!).

What can be done?

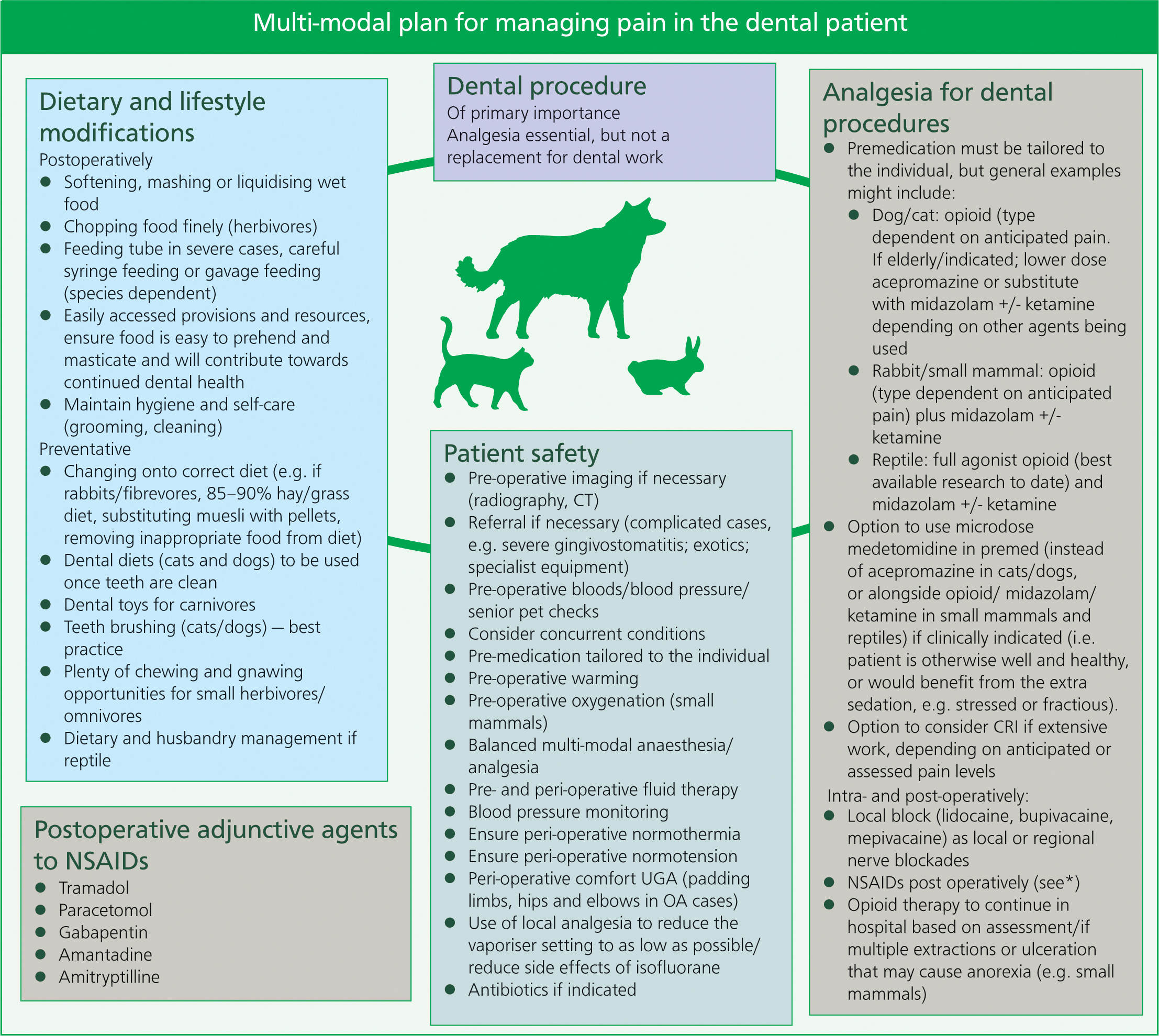

See the multi-modal plan for managing dental pain (Figure 6).

Nursing considerations

A pet having a dental is a worrying time for owners, as often the pet is elderly. There is a prevalent fear among pet owners ‘that their pet is too old for an anaesthetic’, and this can be a reason why owners do not bring their elderly animal in for check-ups. Nurses are in a good position to allay owner fears, and explain that you cannot ‘do nothing’ in the face of dental disease; intervention is necessary; and the safety and extra precautions that are taken for the elderly pet undergoing anaesthesia will reduce the risks of problems occurring.

Although Figure 6 advises nursing considerations for a dental patient, prevention is always better than cure. Being pro-active with dental care, such as correct diet and tooth brushing with dogs and cats; and in the case of rabbits and rodents, appropriate diet and gnawing opportunities, is essential. A patient that already has dental disease needs a dental, and ensuring patient wellbeing during this time by ensuring safe anaesthesia protocols and multi-modal analgesia are used is fundamental. Post-operatively, easily chewable or liquid food, the use of a short-term feeding tube if necessary, good postoperative analgesia, and regular nurse checks are essential to managing dental disease in any species.

Cancer pain

It is difficult to estimate prevalence of cancer in companion animals, but there is reason to suggest that prevalence is significant (Lascelles, 2017). Cancer is becoming more readily diagnosed in pet reptiles, particularly bearded dragons (Rowland, 2016), pet psittacine birds (Castro et al, 2016), and from the author's limited experience with small mammals, is a fairly frequent occurrence in the ferret, rat and African pygmy hedgehog.

In human cancer patients, pain is reported in 30–60% of humans at the time of diagnosis, and 70% or more of those with advanced stages (Fox, 2010). This can commonly be neuropathic pain, which can originate from nerve root compression, direct pain from the lesions, and muscle spasms from the lesions and infiltrated tissue.

Pain can occur from visceral stretching and flow obstruction.

Not all tumours are painful (Lascelles, 2017) and in humans, leukaemia and lymphoma are considered least painful, but still have the potential to cause pain. However, research in cancer pain in veterinary patients is scarce and difficult to assess. Pain in animals in general is difficult to assess, and cancer pain would vary between type and individual, and it is often necessary to extrapolate from is what is known in humans.

Tumours known to be associated with pain include:

- Primary bone tumours

- Metastatic bone tumours

- Multiple myeloma

- Central nervous system (CNS), e.g. spinal

- Inflammatory, e.g. mammary

- Lower urinary tract, e.g. prostate

- Oral, especially if bone involved

- Invasive cutaneous

- Intrathoracic, especially if disseminated

- Intra-abdominal, especially if traction on root of mesentery, obstruction or organ distension (Lucroy, 2013).

Current thought is that stronger analgesics need to be used sooner (Goldberg, 2017b). In any chronic painful condition, analgesia needs to be increased or adjusted, or adjunctive agents added in, alongside other therapies, as the animal's condition deteriorates.

What can be done?

There are three approaches described in managing cancer pain, and similarly to other chronic pain states, treatment is multi-factorial and holistic:

- Aiming to control the disease process itself (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy)

- Approaches to change transduction, transmission, perception and sensation of pain, of which there are pharmacologic, non-pharmacologic, and interventional modalities

- There are a number of interventions to reduce overall suffering and maintain quality of life; ‘the basic tenets of palliative care’ (Looney, 2010).

See the multi-modal plan for managing pain associated with cancer (Figure 7).

Nursing considerations

Cancer patients are challenging because the disease process is dynamic and ongoing. Nurses are in a great position to be able to support owners. Nurses are best to advise on holistic care of the patient, such as ensuring the patient is able to carry out their basic activities of living, but also enjoy their life and are still able to do their favourite things at home. It stands to reason that painful cancer patients will likely benefit from many of the rehabilitation modalities indicated in other chronic pain states: acupuncture, physiotherapy, thermotherapy and massage will be useful for ongoing comfort, alongside good analgesia.

There is a lot that nurses can do to help the veterinary cancer patient in terms of modifying their lifestyle and environment, either in hospital, or helping the owners at home. Many of the lifestyle modifications that can benefit a cancer patient are unique to the type of cancer, the disease process/stage and, of course, the individual.

For two useful chronic pain scales, see the Helsinki Chronic Pain Index (https://www.fourleg.com/media/Helsinki%20Chronic%20Pain%20Index.pdf) and BEAAAAPP Pain Scale for Dogs (https://www.pethospice.com/products/recognizing-pain-in-pets).

Emotional wellbeing: fear and anxiety in end-of-life patients

Chronic (and acute) pain as well as cognitive dysfunction are both likely to occur in elderly and end-of-life patients. Both pain and cognitive dysfunction are causes of fear and anxiety in end-of-life animals.

In the case of persistent pain, it can be the emotional component of pain that can dominate the life of the sufferer (Reid et al, 2015). Pharmaceutical interventions such as anxiolytics, and low dose sedation, will benefit animals if they appear anxious or fearful, despite being on appropriate treatment for their pain. In some (rare) end-of-life cases, it may be that an animal is best (only) kept comfortable if under proportionate palliative sedation, either while waiting for a euthanasia decision, or if owners wish their pet to die naturally (Jones, 2014).

In anxious patients that are painful, pain should be treated first. If anxiety continues and pain management has been re-evaluated and re-implemented based on assessment, and it is determined that the pain is controlled, it is then appropriate to add in anxiolytics.

Conclusion

The pain management plan is individual to the patient, and dynamic (it needs to be re-assessed, re-evaluated and reimplemented often). This is similar to an end-of-life plan — care should be tailored to the individual, the caregiver, and adjusted over time.

Nurses are the best advisors and communicators of holistic care to the pet owner, by ensuring the pet is not only ‘existing’, but also enjoying their life. This perspective is exemplified by Wathes (2010), in that there are three basic quality of life categories, on a continuum:

- A life not worth living

- A life worth living

- A good life.

Nurses are in an excellent position to help owners maintain a ‘good life’ for their pet. Helping the owners at home is a potential role for the proposed idea of ‘District Veterinary Nurse’, outlined in VN Futures (2016).

The range of pharmaceutical agents, lifestyle and environmental modifications, rehabilitation and alternative therapies, and the information available to veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses on palliation and hospice care, means that the opportunities to help patients, right up until the end, are vast. Part two of this series of articles Looking after the end-of-life patient will provide case studies.

KEY POINTS

- There is a fifth life stage after geriatric: ‘end-of-life’. However, end-of-life can occur during any life stage.

- These end-of-life animals are likely to have a high prevalence of under-recognised, under-diagnosed and under-treated chronic pain.

- These chronic pain conditions can, with careful consideration, on-going assessment, evaluation and communication with the owner, be very effectively managed.