References

Nurses' views of pet owners: online pet health information

Abstract

Background

Most research investigating online pet health information has focused on the views of veterinarians or clients with little attention given to the views of veterinary nurses.

Aims

To investigate the views of UK veterinary nurses in relation to pet owners’ use of online pet health information.

Methods

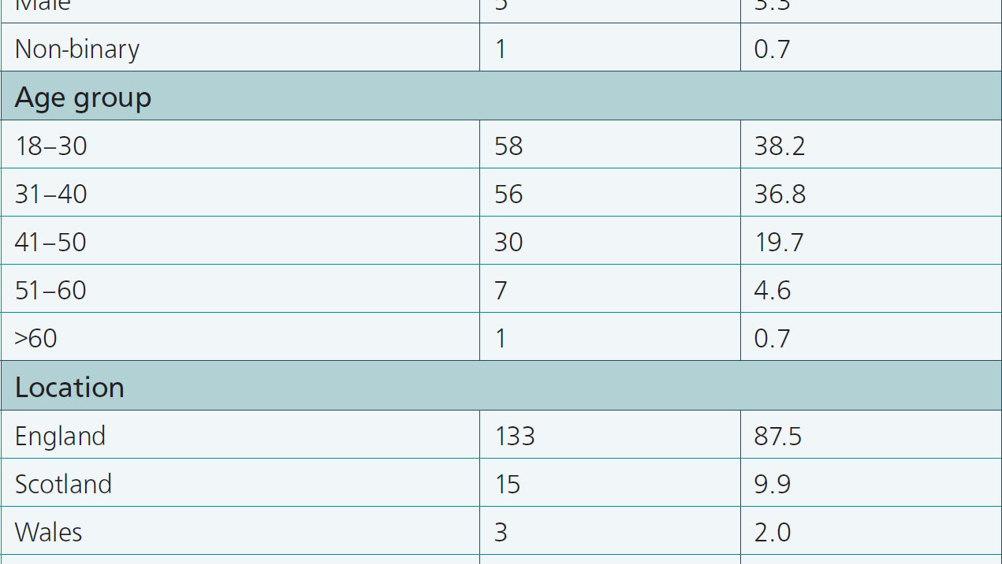

An anonymous online survey was distributed via social media platforms.

Results

Most respondents report thinking that less than half of their clients understand what they read about pet health online, yet the majority do not provide pet health website information to their clients.

Conclusions

Most responding veterinary nurses feel online pet health information has a negative impact on the client/veterinary nurse relationships. It is suggested that veterinary nurses take a proactive role via information prescriptions to guide information seeking behaviours of pet owners.

Internet use in the UK continues to grow; as of 2019, 87% of adults reported using the internet nearly daily and for adults between 16 and 44 years of age this number increases to 99% (Office for National Statistics, 2019). One primary use of the internet is searching for health-related information. The use of online consumer health information has increased dramatically over the last decade, with the internet now the most popular source of human health information (Prestin, 2015; Jacobs, 2017; Bujnowska-Fedak, 2019). The percentage of people who report searching online for health information has grown from 54% in 2018 to 63% in 2019. Women look for health-related information online more often than men; 68% of women report health searches compared with 59% of men (Office for National Statistics, 2019). Reasons for this popularity include the vast amount of readily accessible health information available online and the increased engagement of people in their own health care (Amante et al, 2015; El Sherif et al, 2018). Specific topics sought by UK residents include searching for a symptom or self-diagnosing (reported by 73%), followed by how to manage a condition or illness (63%), obtain information on health improvement (39%), research potential medicines and treatments (39%), and risks associated with a procedure (38%) (Statista, 2015).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.