Urolithiasis is considered to be a common disorder of the urinary tract in dogs (Osborne et al, 2000), with some breeds being more highly represented for certain uroliths than others. Breeds found to be significantly over-represented for calcium oxalate uroliths included the Chihuahua, miniature poodle and Yorkshire terrier. Staffordshire bull terriers and English bulldogs were at increased risk for cystine uroliths (Roe et al, 2012).

Clinical signs of urolithiasis may be the first indication of an underlying systemic disorder, or defect in the structure or function of the urinary tract. As with feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), urolithiasis should not be viewed as a single disease process, but rather as a sequel of underlying abnormalities. Examination of the urolith composition will aid in determining the aetiology. A full dietary history is required, along with blood serum biochemistry and urinalysis of the concentration of calculogenic mineral, crystallisation promoters and crystallisation inhibitors. Urinary diets for dogs (and cats) can be divided into those that promote dissolution through changing the pH of the urine, and those that act by diluting the concentration of the urine. In all cases, dietary management should only commence once obstruction (if present) has been resolved. The aim of this article is to look at the different nutritional managements that exist for the different canine uroliths that are seen in veterinary practice.

Nutritional management

Canine urolithiasis is a disorder that needs close monitoring long term due to the nature of reformation of crystals and stones. Dissolution and prevention of any future stones and crystals is the main aim of longterm management, and this can be achieved by several means that can be monitored by veterinary nurses within a clinic setting. The other main aims are to:

Where dissolution of uroliths is possible with medical management (Table 1), this should be instigated rather than surgical intervention. There are several reasons for this: not all stones and crystals will be removed during a cystotomy and suture material can act as a nidus for further urolith formation. Calcium oxalate uroliths cannot be medically managed and will need surgical intervention (Figure 1).

| Type of urolith | Urinary pH during formation | Target urinary pH | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Struvite | Alkaline | 5.9–6.3 | Calculolytic diet or surgical removal |

| Calcium oxalate | Variable but usually acidic | 7.1–7.7 | Surgical removal |

| Ammonium urate | Acidic | 7.1–7.7 | Calculolytic diet and allopurinol |

| Cystine | Acidic | 7.1–7.7 | Calculolytic diet or surgical removal |

| Silicate | Usually acidic | 7.1–7.7 | Surgical removal |

Clinical nutrition

The nutrition recommended for management of urolithiasis can alter slightly depending on the type of stone or crystal present, and therefore clinical nutritional recommendations for specific stones are discussed separately. The consumption of water, however, is the same no matter which type of stone is present.

Water

Water intake is a vital factor in dogs with, or those that have a predisposition to, canine urolithiasis. The solute load of the diet influences total water intake by a large factor, the same as with cats. The use of a moist diet can aid in increasing water consumption in some dogs that do n0t drink enough. Adding additional water to the diet can be useful in some cases, but can alter the palatability of the diet for some. Encouragement to increase the consumption of water can also be achieved by increasing access, for example by placing more bowls of water around the dog's environment. Use of bottled, pre-boiled water or water that has been left to stand will have little or no chlorine that can be detected by the dog, and this will make it more palatable to some dogs. Some dogs will also play with/eat ice cubes, which is especially useful in the warm weather, or will drink flavoured water. Fruit juices can be good, meat/broths can contain minerals and salts, and their use depends on the type of uroliths present (see Box 1).

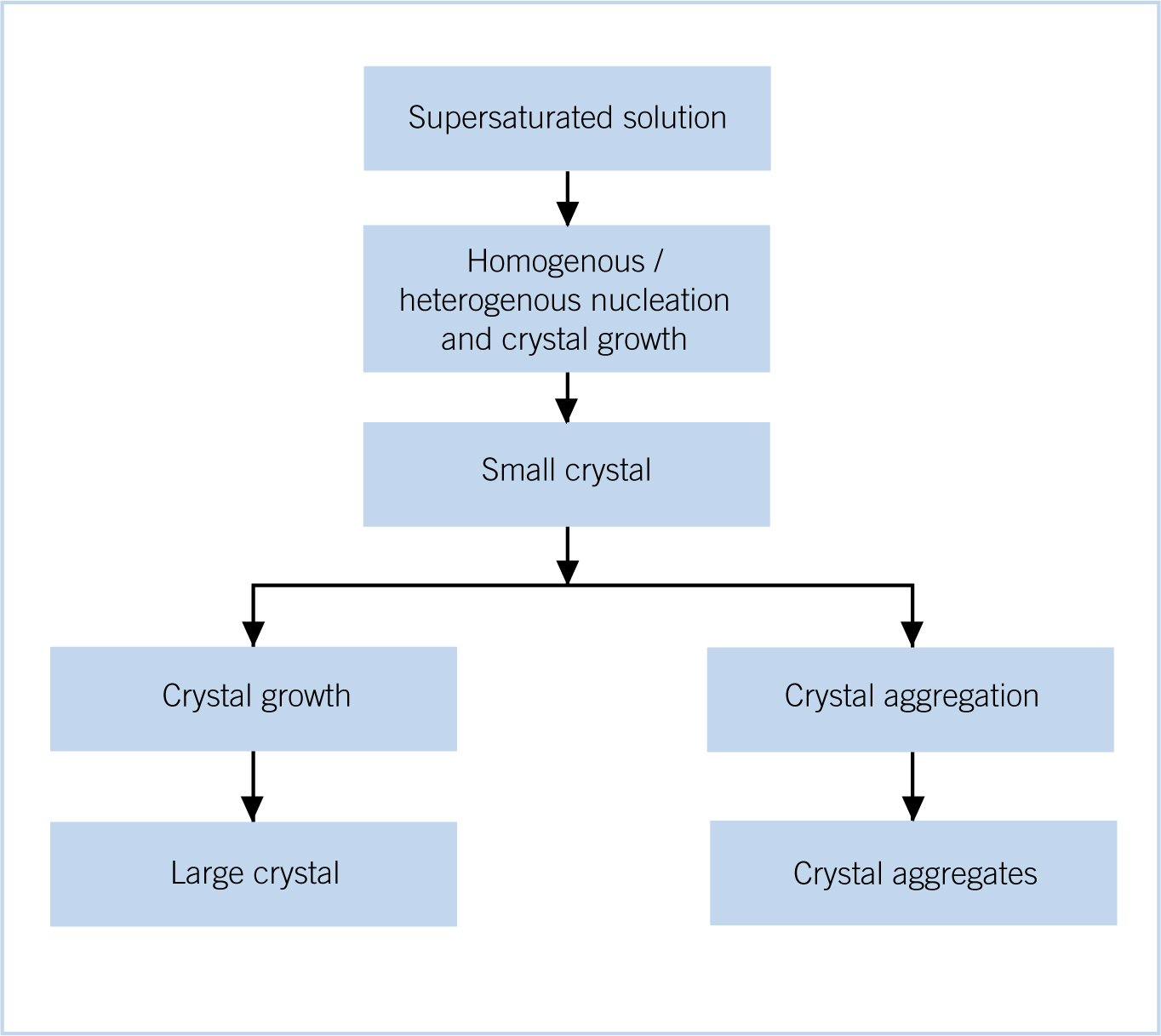

Increases in water consumption will increase the total volume of urine produced. Crystals precipitate out into the urine when supersaturation occurs. Urine becomes saturated when the salt content completely dissolves within the fluid. Any additional salt or decrease in the relative fluid volume will result in precipitation of the salts, urine at this stage is said to be supersaturated. Supersaturation of the urine is the initial stage of crystal urolith formations (Figure 2). Although urine supersaturation is fundamental for the formation of uroliths, the whole process is a complex and multifactorial (Osborne et al, 2000). Veterinary professionals are recommended that the animal's urine should remain dilute and have no strong smell. Bitch's urine does bleach/kill the grass where urination commonly occurs. This does not indicate that crystals or uroliths are present. The use of filtered water in hard water areas can aid in reducing the intake of minerals, such as calcium carbonate which is found in hard water areas. Many small breed dogs will urinate less frequently than larger breed dogs (Stevenson and Markwell, 2001). These small breeds do need to be taken out more often to urinate; access to the garden where the door if left open or a dog flap is present, may not ensure that the dog is urinating more frequently, and supervising the dog and giving the command to urinate may be beneficial (Perea, 2009).

Urate urolithiasis

Dalmatians have a high risk factor for recurrent urate uroliths, high enough that prophylactic therapy should be actively considered for this breed. Some texts state that Dalmatians are more susceptible because they lack the enzyme uricase, which converts uric acid to allantoin. Their urine therefore contains higher levels of urates than other breeds (Agar, 2001). However, other texts suggest that uric acid metabolism is not caused by the absence of hepatic uricase (Senior, 1996; Buffington et al, 2004), with uricase enzyme levels in Dalmatians being comparable to that in other breeds. The cause has been attributed to the impaired transport of uric acid into the hepatocytes, which may reduce the rate of hepatic oxidation. Another factor can be attributed to the proximal renal tubules of Dalmatians reabsorbing less and secreting more urate than the kidneys of other breeds of dogs (Buffington et al, 2004).

Nutrition aims of dietary management of urate urolithiasis include:

Proteins

The diet designed to aid in management of urate urolithiasis can have overall restricted levels of proteins (1.6–2.2 g protein/100 kcal metabolisable energy (ME)) (Senior, 1996), especially those proteins that contain larger amounts of nucleic acids, as they contain purines, e.g. protein from muscle or organ tissues. Milk proteins (casein) and eggs provide a suitable source, as they contain a lower amount of purines, but also have a high biological value, which is required when a restriction on protein levels is required in the diet. Box 1 gives a list of different foods that are high, medium and low purine content.

Allopurinol is a xanthine oxidase inhibitor, which reduces the rate of urate excretion into the urine. It decreases the production of uric acid by inhibiting the conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine, and xanthine to uric acid. Allopurinol needs to be added to the diet when dissolution of urate uroliths is required, although checking the dietary manufacturers' guidelines is recommended. A dose rate of 15 mg/kg per os (PO) twice daily (BID) should be utilised, although dose rate is dependent on the individual (Osborne et al, 2000).

Carbohydrates and fats

Due to the restriction in protein levels, it is important that there is a sufficient supply of non-protein calories. A higher than normal fat content can arise as a result (20% dry matter basis (DMB)), and care should be given to weight control of the animal. The level of fats also aids in obtaining the preferred urine pH.

Vitamins and minerals

As with any disease or disorder which has clinical symptoms that include polyuria, the water-soluble vitamins should be supplemented. With urolithiasis however, vitamin C should not be supplemented as it is a precursor of oxalate, and can predispose to its formation.

The alkalising agent used in these diets is commonly potassium citrate and calcium carbonate. If the target urinary pH is not reached, then additional potassium citrate can be added to the diet at a starting dose rate of 50–100 mg/kg bodyweight PO BID, the amount given to effect (Senior, 1996).

Struvite uroliths

Struvite uroliths in dogs, as in cats, are the most commonly occurring urolith in the UK and USA, though their incidence rate is decreasing (Buffington et al, 2004). Infection induced struvite uroliths are common in dogs and a positive culture result should prompt initiation of antimicrobial therapy alongside nutritional management. The bacteria present tend to be urease-producing Staphylococci.

Nutritional aims of dietary management of struvite uroliths include:

Proteins

Restricted levels of protein are required (1.47 g protein/100 kcal ME) for management of struvite uroliths (Osborne et al, 2000), but a high biological value is needed. When protein levels are this restricted it is not advisable to be feed this diet in the long term. The urine acidifying substance in diets designed for struvite dissolution is DL-methionine, used at a dose rate of 0.5 g/kg of diet (Osborne et al, 2000).

Carbohydrates

The majority of calories obtained from the diet need to be obtained from a non-protein source. Thus, proportionately the carbohydrate and fat levels of the ME are increased in these diets.

Fats

Struvite diets can have very high fat levels (~26% dry matter (DM)), so much so that in some brands only tinned formulas are available. Feeding diets with this high a fat content to dogs with hyperlipidaemia, pancreatitis or even at risk groups (such as Schnauzers and Spaniels) is contraindicated.

Vitamins and minerals

Decreased amounts of phosphorous (24 mg phosphorus/100 kcal ME) and magnesium (3.3 mg magnesium/100 kcal ME) are present in diets designed to aid urinary tract issues, as these are the constituents of the struvite urolith (Osborne et al, 2000). Sodium levels are often increased in these diets, in order to increase water intake (23.3 mg sodium/100 kcal ME). The antioxidants vitamin E and beta-carotene are often supplemented, as they help to reduce oxidative damage, and help to combat urolithiasis. As an oxalate precursor, vitamin C should not be supplemented when feeding diets designed for struvite dissolution.

Calcium oxalate uroliths

Calcium oxalate uroliths are the second most commonly occurring uroliths in the dog.

Nutritional aims of dietary management include:

Protein

A low protein diet is required with levels of 1.6–2.2 g/100 kcal ME have been suggested (Senior, 1996), in cases where calcium oxalate uroliths are present.

Fats and carbohydrates

Non-protein calories are required in the diet, in order to prevent protein catabolism. Thus, levels of fats and carbohydrates are higher than normal, for example fat can be as high as 26% DMB, and carbohydrates 60% DMB. Weight management can be a problem in dogs that are predisposed to weight gain.

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamins D and C should not be supplemented into the diet. Vitamin D increases the absorption of calcium from the diet, whereas vitamin C acts as a precursor to oxalates. The levels of calcium in the diet should be restricted, but not reduced, as with levels of sodium. Restricted calcium levels are approximately 0.68% DMB. Sodium increases calcium excretion into the urine, and a dietary level of 0.1–0.2% sodium DMB or 45–55 mg sodium/100 kcal ME is recommended (Senior, 1996). The digestibility of the diet and the individual's absorption ability of vitamins and minerals will vary greatly, and thus monitoring of levels may be required.

Cystine urolithiasis

Cystine uroliths are uncommon in both cats and dogs, but arise due to a metabolic defect where the reabsorption of filtered cystine in the proximal tube is impaired (Bovee, 1984). Once in the urine cystine is very insoluble, especially in acidic urine.

Nutritional aims in the management of cystine uroliths include:

Protein

A low protein diet is required (9–11% protein DM), as this will aid in the reduction of the total daily excretion of cystine (Osborne et al, 2000).

Carbohydrates and fats

Due to the low levels of protein in the diet, calories have to be obtained from the carbohydrates and fats. Care should be taken with diets that are high in fats, as described in the section on diet designed for struvite uroliths.

Vitamins and minerals

Low sodium levels are also required as sodium excretion can enhance cystine excretion. Low sodium in combination with low protein levels tends to increase the urine volume, which further decreases the urinary concentration of cystine (Senior, 1996). In order to create an alkaline urine pH, supplementation with potassium citrate (50–100 mg/kg bodyweight PO BID) is required.

Silicate uroliths

Silicate uroliths are more commonly seen in male dogs (96%) than females (4%) (Osborne et al, 2000), most likely due to females being able to pass smaller uroliths before they can induce clinical signs. Foods that contain large amounts of plant-derived materials, are thought to be a predisposing factor for silicate uroliths, another factor being the consumption of soil, as silica in the soil passes through to the plants and is readily absorbed via the intestines.

Dietary management of dogs suffering from silicate uroliths is through prevention. Change of the diet to one that does not contain large amounts of plantderived materials, and increases the volume of urine produced, are the main factors. There is debate about the urinary pH levels; alkalisation of the urine in order to increase the solubility of silica is unknown.

Feeding a dog with urolithiasis

Nearly all diets aimed at dissolution or prevention of uroliths, are potentially high in fat levels, mainly due to the requirement for non-protein calories. Care should be given due to the high fat content when transitioning the diet. Caution should also be given to those dogs that are likely to gain weight, or those that are predisposed to hyperlipidaemia or pancreatitis. Diarrhoea can occur when high fat levels are fed, and a combination with a high fibre diet, which is aimed at urolith prevention, may be required.

Calculolytic diets are only successful when fed alone. Addition of treats and home-cooked foods can undo the desired effect of the diet. It is equally important that the urolith analysis is correct. Stones, which are of mixed composition, are difficult to dissolve and surgical removal may be the treatment of choice. In dogs suffering from struvite urolithiasis, if there is suspicion that additional snacks or treats are being fed, a blood sample analysis can be useful. In dogs being fed certain veterinary struvite dissolution diets, a low plasma urea concentration of less than 4 mmol/litre (BUN 10 mg/dl) is found (Osborne et al, 2000). Above this level additional feeding is suggested.

Monitoring of dogs suffering from urolithiasis is vital, this includes bodyweight and body condition. A full nutritional assessment should be performed on every pet at every visit (WSAVA, 2012). Urinalysis should be performed at least every 6 months once dissolution has occurred. Preventative measures involve feeding a diet that promotes the correct urine pH, promotes undersaturation of the urine, provide calories from a non-protein source and is relatively low in the salts that are the building blocks for the uroliths that the animal suffers from.

Conclusion

Dogs that have suffered with any form of urolithiasis need to have regular urinalysis while on the diet, including pH and having microscopy performed. Client education can be key in prevention in at risk breeds, and those that are over their ideal body condition score. This includes increasing water intake as much as possible in all groups, and the frequency of urination.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: none.