References

Obesity in cats and dogs: simple things you can do

Abstract

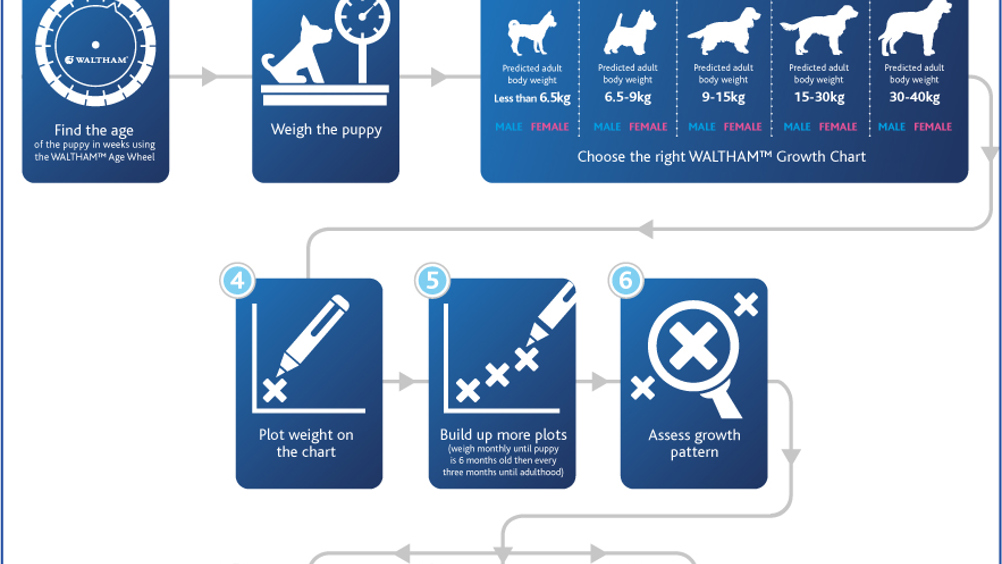

Obesity in cats and dogs, is a complex and incurable (but treatable) disease which negatively affects quality and longevity of life. The rising trend is concerning for both pet owners and the veterinary profession. This disease can feel an overwhelming one to tackle at times but there are some simple steps that can be implemented to make a difference. Talking openly about pet obesity, without judgement can improve trust with pet owners, making conversations about cats and dogs with obesity easier. Weighing and body condition scoring pets regularly, from early on in life and recording these values allows trends to be spotted more easily. This means any reactive nutritional recommendations and/or feeding behaviour changes can be made and implemented earlier. Recommending a diet appropriate to the pet's caloric needs, while ensuring meal satisfaction and limiting food seeking behaviour, can go some way towards achieving or maintaining a healthy weight and owner compliance. Combining these nutritional recommendations with daily weighing of the recommended diet on digital scales can also be beneficial. If we all implement some small changes in the way we approach cats and dogs with obesity or indeed those at risk of having obesity, we can make a difference.

It is widely recognised that obesity in cats and dogs is a complex, multifactorial (Loftus et al, 2014), incurable (German et al, 2009, 2011a) disease (Day, 2017). Obesity in pets reduces their quality of life (German et al, 2012) and their lifespan (Kealy et al, 2002), and it was the top welfare issue identified by veterinary practices in a recent survey (PDSA, 2020). One study reported median lifespan was shorter in overweight dogs or dogs with obesity when compared with an ideal weight (Salt et al, 2019). In cats a similar observation was made, with shorter lifespans where the cat was overweight or obese (Teng et al, 2018). With 65% of all dogs, 37% of juvenile dogs and 39% of cats in the UK reported to be overweight or have obesity this disease is affecting pets at epidemic proportions (Courcier et al, 2010; German et al, 2018).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.