When a breakdown in the practice-client relationship occurs, an effective complaint handling procedure enables practices to redeem themselves in an unhappy client's eyes. Indeed, research has shown that a customer whose complaint has been handled well, is more likely to remain a customer afterwards and to continue to make future purchases than if they had never experienced a problem at all (Rothenberger et al, 2008). It is as if effective complaint handling demonstrates the extent to which a company cares, which may not always be apparent during the normal course of business.

Of course, it is far better for a complaint not to have arisen in the first place, but since it is impossible to please all of the clients all of the time, occasional complaints are an inevitable fact of life, no matter how well organized the practice. To minimize the occurrence of complaints, practices need to do two things — ensure that they are doing all they can to prevent complaints arising in the first place, and ensure they have effective procedures in place for dealing with a complaint once it has arisen. The first task is about effective client communication and the second is about successful service recovery so that a valued client is not lost. Many clients who have an issue with their practice do not bother to complain — they simply go elsewhere. This is the worst case scenario, because the practice may continue to remain ignorant of what it is doing wrong with the inevitable consequences. When clients have a complaint, they need to be able to express it without feeling awkward or guilty. They also need to be willing to give the practice the opportunity to learn and to improve the service it provides. In this way, complaints represent valuable and useful client feedback.

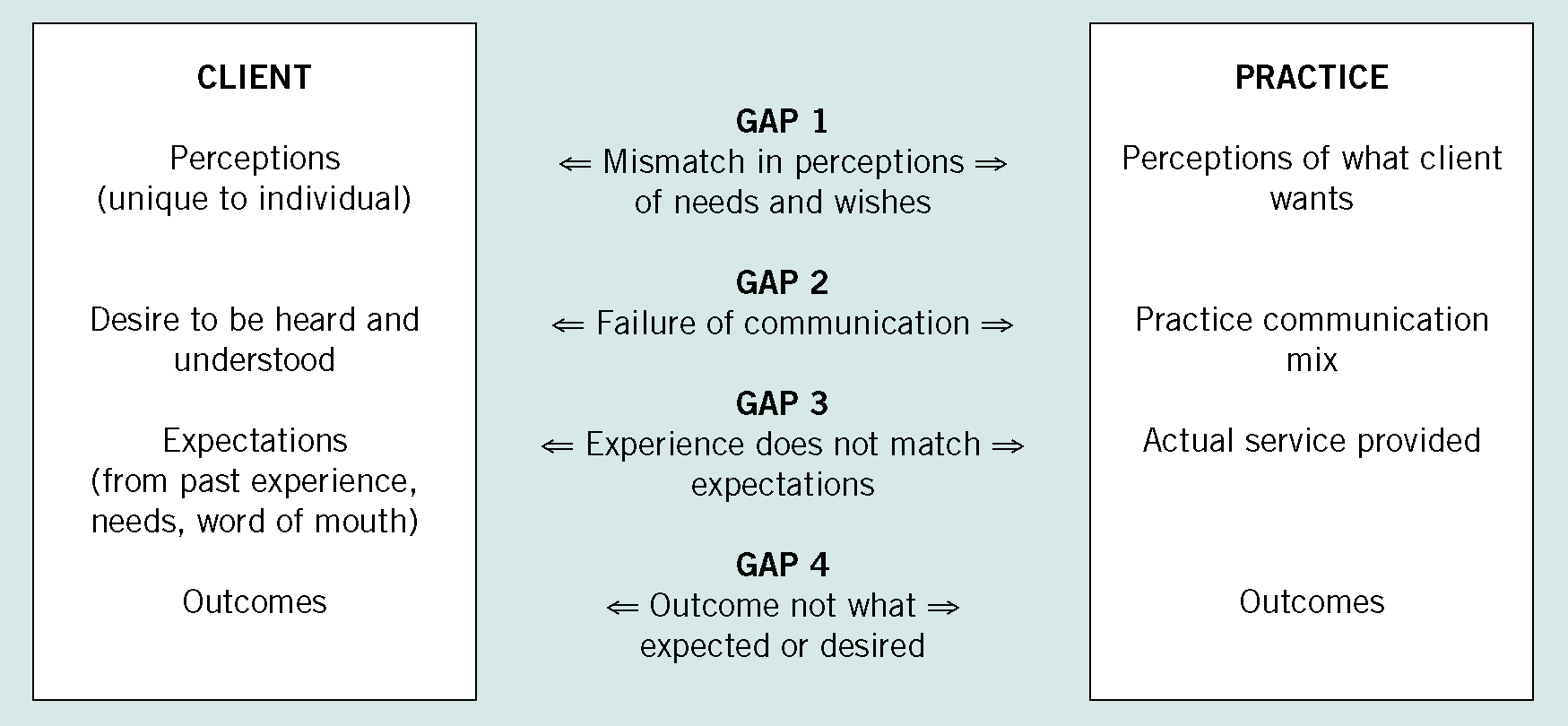

The purpose of this article is twofold — first, to draw on research carried out within other service industries to identify the service quality gaps that can occur in veterinary practice and discuss how these might be filled to prevent complaints arising and, second, to outline a best-practice approach to complaint handling, which will help practices to keep valued clients who do take the trouble to complain.

Preventing complaints

Parasuraman et al (1985) conducted studies of the quality of the services provided to clients by a wide range of different service organizations. This research led to the identification of a number of generic ‘gaps’ in service quality, which appeared to be common to all the providers and which tended to cause client dissatisfaction leading to complaints. Parasuraman et al (1985) produced a ‘gaps model’ of service quality, which was widely accepted as being universally applicable at the time and is still very useful today. The concept of ‘quality gaps’ was drawn upon to derive a veterinary practice-specific ‘quality gaps’ model (Figure 1).

Gap 1: client perceptions

Clients' assessments of the quality of the service provided will vary. Perceptions are unique to the individual — a good experience for one client may be a mediocre experience for another. This variation in individual perceptions makes it difficult for veterinary practices to please all of their clients all of the time.

A client perceives that a veterinary surgeon is competent if the consultation went well and the treatment prescribed results in the pet getting better (Orpin, 1995). However, pets can die despite the best efforts of the veterinarian and other staff. The client is then left with a bill to pay and is often inconsolable, because of the loss of a very dear friend and member of the family. If there has been poor communication, this will most certainly contribute to the client placing the blame with the veterinarian and concluding that their pet died because of an error or incompetence.

In the UK, The Veterinary Defence Society, which provides professional indemnity insurance cover to veterinarians (amongst other services), has noted an increase in complaints made against veterinarians being referred to the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS), the regulatory body, which represents the interests of the UK pet-owning public (McKeown, 2010). A major cause of such complaints is a breakdown of communication between veterinarian and client. Bonvicini and Cornell (2008) that in the USA the most common causes of litigation in veterinary practice were clients' perceptions that the veterinarian did not care, imparted information badly and failed to listen.

Gap 2: failure of communication

These negative perceptions can be avoided through good communication from the outset. Because veterinarians rely on clients for information about their animal's condition, they need to have excellent communication skills, which enable them not only to elicit key information in a way that allows for a correct diagnosis and treatment plan, but also to impart information to owners in a way that helps them to understand and to make informed choices. In the UK, veterinary schools now provide communication skills training as part of their veterinary curricula, but this is a relatively recent development. Veterinary nurses, on the other hand, have received communication skills training as part of their veterinary nursing training for many years and most have excellent communication skills, which can and should be utilized fully in order to build positive client relationships. Often a client will feel much more comfortable talking through their concerns with a veterinary nurse rather than the veterinarian.

Gaps 3 and 4: experience and outcomes

A negative outcome does not automatically mean that a client will take his or her business elsewhere. While an unhappy client is still willing to maintain communication with the practice, there is hope of a resolution and a chance to put things right. It is only when an unhappy client ceases all communication with the practice, that the client is lost forever. Occasionally, staff may feel that some clients are not worth the effort required, because they are more trouble than they are worth, but research has shown that a satisfactory resolution of a complaint turns an unhappy client into an ambassador for the practice and this should certainly be considered.

Resolving complaints

Davidow (2003) reviewed around 60 empirical studies on organizational responses to complaints and came up with six important dimensions of complaint handling, which when addressed properly, can substantially improve an organization's complaint-handling procedures:

- Timeliness

- Facilitation

- Redress

- Apology

- Credibility

- Attentiveness

Timeliness

Having a complaint dealt with promptly is important to clients, but there are occasions when it is not possible to resolve a complaint immediately. Some delay may be necessary pending investigation. In these situations, it is important to agree a time frame with the client and to ensure that they are aware of the reasons for the delay. Empowering staff to solve the problem immediately has a significant positive impact on client satisfaction. Experience of handling complaints within a busy referral veterinary hospital bears this out — clients nearly always preferred to speak to someone about their complaint rather than to write it down using the available complaint form. Only after they were allowed to vent their frustrations to a member of staff face-to-face, were they willing to consider putting their complaint in writing.

Facilitation

Hart et al (1990) observed that most unhappy people do not speak up for a variety of reasons. They may think that the situation is hopeless or they don't want to create a scene or they simply cannot be bothered to write a letter or make that telephone call. Davidow (2003) recommends that service companies ensure that clients are able to complain and that there are clear guidelines available for making a complaint. A simple leaflet available for clients to pick up in the waiting room explaining what they need to do to make a complaint is often sufficient. Although there is some evidence that making a complaint handling mechanism simple and easy for clients to use actually increases the likelihood of complaints, equally, it has been shown to reduce subsequent negative word-of-mouth (Davidow, 2003.) This finding is supported by Rothenberger et al (2008) who found that satisfaction with complaint handling was key to consumer recommendation of the service to others. Hogarth and English (2002) argue that the ability to make complaints, have them investigated and then to receive feedback empowers consumers.

Redress

Compensation should, of course, be offered as appropriate to the complaint. It is not always possible to resolve a complaint in the client's favour, but gestures of goodwill such as money-off vouchers, a reduction in the amount of the bill and a sincere apology can help improve the relationship between the practice and the client, as will a genuine desire to put things right. It must be madeclear, though, that these things are not admissions of guilt, but rather an acknowledgement of a client's distress and a signal that the practice values the client and their custom.

Apology

Apologies should always be sincere — a client will be able to tell when they are not and this will make matters worse. To make a sincere apology, staff need to care enough, so practices must ensure that their front line staff are naturally caring and empathetic people who appreciate the importance of the client. Over time staff can become desensitized, jaded or even bored with their roles and this can transfer to their attitude towards clients. A programme of staff development and training and varying duties and responsibilities will keep employees interested and fresh. Many practices share out the reception duties between the available veterinary nurses and part-time receptionists. This can work to maintain a freshness of approach, but it is essential to ensure that these employees are well trained, have all the necessary knowledge about practice policies and procedures and, of course, excellent communication skills. Also, clients need to see a seemless, joined-up approach as well as consistency of treatment and information, no matter how many different people there are on reception throughout the working week. A client who has made a complaint to a receptionist at six o'clock on a Friday evening does not want to wait for something to be done about it until that same receptionist is back in the practice the following Wednesday.

Credibility

It has been shown that if the service provided to date has been generally good and the client has had a good experience, this does reduce the impact of a poorly handled complaint (Tax et al, 1998). However, although the client is more willing to forgive, he is not likely to forget, because a poorly handled complaint will erode the trust that has been built up between the client and the practice. The practice will then have to work very hard to rebuild this trust. The complaint handling process must be credible — in other words, if a practice promises prompt action, it must deliver this. Promises must be kept and actions carried out in a way that demonstrates the practice's reliability and trustworthiness.

Attentiveness

A client who makes a complaint should be listened to carefully and attentively. Whatever form the complaint is made in, by letter, telephone or face-to-face, clients should be able to feel that full and proper attention has been paid to them. A complaint by letter should be responded to with a telephone call to the client acknowledging receipt of the letter and thanking them for it and then an explanation of what will be done and when. The client should be allowed to give their side of the story again and to talk for as long as needed. Such calls can be lengthy and at times harrowing, but at no point should the client feel that they are being rushed to terminate the call. They should be allowed to terminate it in their own time. The telephone call should then be followed up with a letter of acknowledgement reiterating the actions that will be taken and the timescale for these. With face-to-face complaints, which cannot be resolved instantly by the receptionist there and then, the client should be given time with the practice manager or veterinary surgeon who dealt with the case to discuss their complaint in detail. Again, as much time should be provided for this as the client needs. The aim should be to ensure that the client feels that they have been given sufficient time and have been listened to well.

Conclusions

To summarize, an effective complaint handling procedure will include all of the following features and actions:

- Staff who welcome complaints as an opportunity to find out what is wrong with the service they are providing and how it can be improved. Not all complaints may be justified, but all complaints are potentially useful tools for improving service quality

- Clearly defined complaint-handling procedures, which all staff are familiar with and follow consistently

- Clear and concise guidelines for clients on making complaints, ensuring that clients are aware that the practice welcomes comments of all kinds — not just complimentary ones

- The ability to act in a timely fashion. Once a complaint is received, it should be acknowledged promptly and acted on as quickly as possible to resolve the problem. If investigation is required, the client should be kept informed of timescales and developments at each stage of the process

- Care and concern for the client who complains — listening carefully, apologizing sincerely and providing appropriate compensation if the practice is found to be at fault

- Giving front line staff the authority to take all necessary and appropriate steps to resolve the complaint immediately without having to pass it on to someone else. To this end, staff should be provided with training and given clear guidelines on practice policies. However, it may not be appropriate for complex or very serious complaints to be handled in this way. In such cases, staff should know what to do

- Providing clients with information and the necessary support to take the complaint further, if they feel it cannot be resolved satisfactorily by the practice

- A complaint recording and monitoring system, which allows analysis of all complaints received in order to identify the gaps in service quality and the ability to act on these immediately

- An interest in and enthusiasm for clients and their pets involving talking to clients and checking with them often that their experience so far has been a good one.

In the UK, the Veterinary Defence Society has produced a booklet for use by practices on handling complaints entitled Complaints and how to deal with them, which is available to practices free of charge from the Society (Bark et al, 2007).

Key Points

- A major cause of client complaints is a breakdown of communication between client and veterinarian.

- Practice staff should welcome complaints as an opportunity to find out what is wrong with the service they are providing and how it can be improved.

- Whatever form the complaint is made in, whether by letter, telephone or face-to-face, clients should feel that full and proper attention has been paid to them and that staff are keen to resolve the problem as quickly as possible.

- A practice's complaint handling procedure must be credible — in other words, if a practice promises prompt action, it must deliver it.