The local tissue response to the cellulose fibres in a retained surgical swab is inflammatory, commonly resulting in aseptic granulomatous encapsulation that may be apparent clinically as a palpable mass (Merlo and Lamb, 2000). The mass formed can have a similar effect on patient health to that of a tumour (Sakayama et al, 2005), both in appearance by diagnostic imaging and initially during surgical exploration. If histopathology is not performed on the mass, this may result in the misdiagnosis of a patient, with potential serious consequences.

The proximity of a gossypiboma to vital structures is significant as invasion of adjacent viscera represents another possible serious consequence of the foreign body reaction that surrounds the swab. Intra-abdominal gossypibomas have been reported as migrating into the ileum, stomach, colon or bladder resulting in obstruction (Wattanasirichaigoon, 1996) and even visceral perforation (Lata et al. 2011). Significant tissue erosion can occur from the fibrous material of the swab, either directly leading to sinus or fistula formation, or indirectly by stimulation of the growth of adhesions post surgery (Jones, 2008).

Gossypibomas that develop early in the post-operative period are usually associated with an exudative response rather than granulomatous encapsulation. The exudative response is generally associated with an episode of abscess formation and potential septicaemia due to secondary bacterial invasion (Manzella et al. 2009).

Incidence of gossypiboma

A gossypiboma is the direct result of iatrogenic harm, as the act of leaving a swab in situ arises from a failure to account for all the swabs at the end of a surgical or other invasive procedure (Jones, 2008).

In human surgery the true incidence of retained surgical swab is unknown, possibly because it represents clear evidence of substandard and negligent care and, therefore, reporting may be inhibited by fear of litigation (Kaiser et al. 1996). Estimates of retained surgical swabs during human surgery range from one case per 8000-18 000 operations (Gawande et al. 2003) to one case per 3000-5000 for coeliotomies (Rappaport and Haynes, 1990).

There are few references to retained surgical swab in animals, and it seems likely that, as in humans, the incidence of this problem may have been underestimated (Merlo and Lamb, 2000).

Most instances of retained surgical swab in humans occur following relatively routine procedures, for example caesarean section or hysterectomy, or when unplanned changes were made to the surgical procedure (Gawande et al. 2003). Merlo and Lamb's (2000) study identified the most frequent previous surgery in veterinary patients as ovariohysterectomy, either as an elective procedure or to treat pyometra. This is in congruence with Forster et al's (2011) retrospective study that investigated the incidence of retained swabs in patients referred to four veterinary referral centres between 2003 and 2010. Thirteen dogs were identified with a diagnosis of retained swab; the initial surgery in five of the 13 cases was ovariohysterectomy while seven of the 13 cases presented following ‘non-routine’ abdominal surgical procedures including cholecystotomy, gastropexy and cystotomy. Of these cases, five were referred as acute cases within 15 days of the ini tial surgery displaying a range of symptoms including vomiting, pain, lethargy and abdominal distension.

Merlo and Lamb's (2000) study examined eight dogs with retained surgical swab; the median elapsed time between surgery and diagnosis of the retained swab was 9.5 months (range 4 days to 38 months).

The most frequent physical finding in the dogs examined was discharging sinus, which was noted in five dogs. In four of these dogs the position of the sinus suggested it was a complication of the previous surgical procedure. Four dogs had a palpable abdominal mass, including two that also had a sinus. One presented as an emergency case with severe vomiting and diarrhoea 4 days after surgery to treat pyometra. None of the dogs displayed signs of abdominal pain. Radiological signs included localised, speckled or whirl-like gas lucency, abdominal mass, and non-focal soft tissue swelling (Figure 1).

The five acute cases in the Forster et al (2011) study and the dogs examined in the Merlo and Lamb (2000) study represented examples of the infected, exudative type of foreign-body granuloma, which is associated with clinical signs that develop relatively soon, often days, after surgery (Choi et al. 1988).

It is however important to note that if a retained surgical swab is encapsulated by an aseptic granuloma, there may be no clinical signs other than a mass, which develops slowly in response to the cotton material. These may remain latent for years, sometimes decades (Gibbs et al. 2007). Miller et al (2006) reported the case of an 11-year-old Labrador Retriever presenting with an extraskeletal osteosarcoma, associated with the granulomatous reaction to a retained surgical swab adjacent to the stifle, 9 years after repair of a ruptured cruciate ligament. Rayner et al (2010) reported the tragic case of a 3-year-old neutered female Rottweiler dog presented for post-mortem examination 2 years after routine ovariohysterectomy, which revealed an abdominal fibrosarcoma surrounding a retained surgical swab. Fortunately neoplastic transformation of retained swabs appears rare, however it is suggested that any excised gossypiboma should be evaluated histologically for the possibility of malignant cells (Miller et al. 2006).

Are humans or animals at greater risk?

Compared with human surgical patients, relatively few veterinary surgeons routinely use radiopaque swabs; operating procedures in veterinary practice are generally less rigorous, and first-opinion practices tend not to designate specific scrub and circulating roles to theatre staff, all of which could contribute to a higher risk for retained surgical swab than in humans. Conversely, most dogs have a much smaller peritoneal cavity than an adult human and, on average, undergo shorter, less complex surgical procedures; both of these factors would tend to reduce their risk of retained surgical swab (Merlo and Lamb, 2000).

Preventing retained surgical items

It is an unfortunate fact that almost all cases of retained swabs are due to poor operating room practice (Hamilton, 2004). Rules and guidelines have been set out for many years in the human medical profession and while a duty of care owed to a patient requires that every effort is made to avoid doing harm to a patient, surgical counting is not yet compulsory under UK law. In 2008 the World Health Organisation (WHO) established the Safe Surgery Saves Lives campaign, an initiative designed to address the safety of surgical care, including the process of surgical counting. This checklist is available from: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/tools_resources/SSSL_Checklist_finalJun08.pdf

The Animal Health Trust (AHT) have modified the WHO surgical safety checklist to make it more appropriate to the veterinary profession, this can be downloaded from the AHT referrals surgery webpage (www.ahtreferrals.co.uk/Surgery.html).

Such documents provide a good starting point for devising a system of working tailored to each individual veterinary practice.

The following guidelines may also be suggested as a starting point for managing the risk of retained surgical swabs:

- Pack swabs in counted bundles for sterilisation (Figure 2).

- Count all swabs at the beginning of surgery. Ensure that each bundle does contain the number of swabs specified — items should be counted individually and audibly by two people (for example, the scrubbed nurse and circulating nurse).

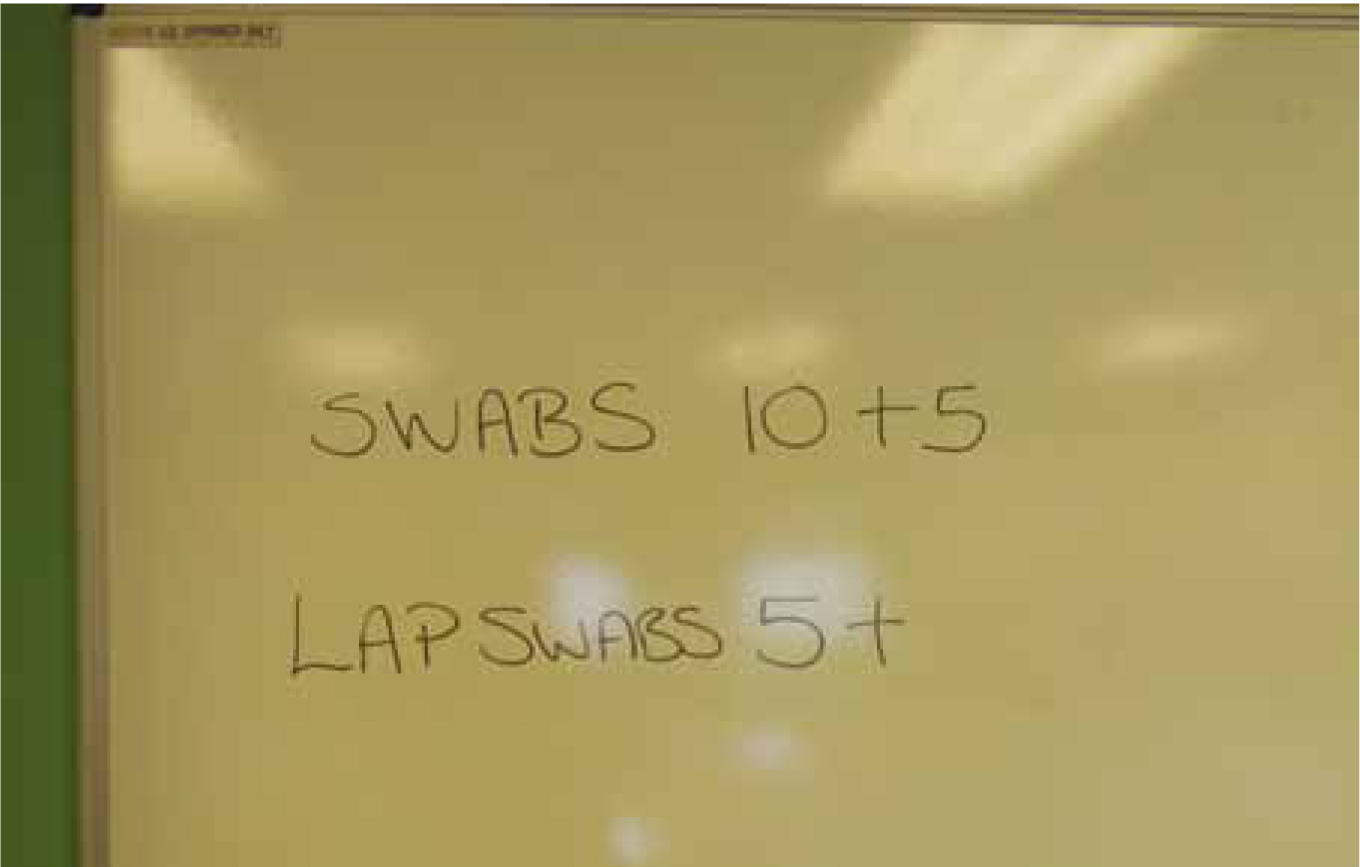

- Provision should be made in theatre for a dry wipe count board. This board should be permanently fixed to the theatre wall and be at a height and in a position that facilitates access and visibility during the procedure. The number of swabs in use should be noted on this board and any additional swabs must be added to this tally (Figure 3).

- Provide the surgeon with a clean, opened individual swab. If this is not sufficient to control haemorrhage then surgical suction is warranted (Hamilton, 2004).

- All swabs that are used during invasive procedures, should have an x-ray detectable marker fixed securely across the width of the swab (Figure 4).

- The use of laparotomy swabs is advocated for many thoracic and abdominal procedures. Laparotomy swabs are much larger than conventional swabs and possess a small tag, which enables them to be attached to the surgical drape, in order to prevent loss (Figure 4).

- At all times during a surgical procedure, the scrubbed nurse must be aware of the location of all swabs, instruments and medical devices. Neatness in approach should be encouraged to ensure that only necessary equipment is in use at any given time.

- During a long procedure, it is usual for swabs to be passed off the sterile trolley, bagged, weighed and recorded. These must not be removed from thea-tre, however, until the end of the procedure.

- If a counted item is inadvertently dropped off the sterile field, the circulating staff member should retrieve it, show it to the scrubbed nurse and isolate it from the field to be included in the final count.

- If any interruption occurs during the counting procedure, the count should be recommenced.

Surgical counts

Counting is an accepted practice in order to mini-mise the retention of foreign objects within the patient. The surgical count should be undertaken using well established and consistent methods of counting on every occasion. Gasson (2007) suggests surgical counts should be performed:

- At the beginning of the case

- Before closure of a hollow organ

- Before closure of a cavity

- At the end of the case.

When checking swabs the scrubbed nurse should ensure the item is fully opened to check its integrity. The surgical team must allow time for these counts to be undertaken without pressure. Staff shortages or other issues that reduce the efficiency of operating theatres should never be ignored, as the consequence may be that patients could be put at risk (Jones, 2008).

Count discrepancy

If any discrepancy in the count is identified, the operating surgeon must be informed immediately and a thorough search implemented at once:

- Re-count items ensuring all items are fully separated — un-bag counted items if necessary.

Call for assistance and perform search of:

- Wound or cavity

- Surgical field and trolleys

- Floor

- All waste containers.

If a search fails to locate the missing item, remain calm but inform the surgeon. The author has located a missing swab on many occasions stuck to the sole or even the inside of a surgeon or nurse's shoe, so ensure the surrounding area is checked thoroughly. If the swab still cannot be located:

- Organise for an x-ray of the surgical site. Good quality radiographs and careful observation are essential as even x-ray detectable swabs are not guaranteed to be visible. The radiopaque line may become twisted, misshapen or hidden behind dense tissue. In a report by Kopka et al (1996) of 13 human patients with a retained swab, the radiopaque marker was only visible on 9 x-rays and even then was not recognised for what it was (Figure 5).

- In human surgery, personnel are required to write an incident report, indicating all efforts and actions undertaken to locate the missing item even if the item is located on an x-ray film. This report has legal significance to verify that an appropriate attempt was made to locate the missing item. It may be suggested to adopt a similar protocol in veterinary practice.

Counting other items

The main focus of this article has been on the prevention of retained surgical swabs, however other items may be lost during a surgical procedure. Surgical instruments may be straightforward to identify on post-operative x-rays, but needles or parts of needles pose a considerable challenge (Woodhead, 2009).

Sharps

Sharps include surgical needles, hypodermic needles, scalpel blades and electrosurgical needles and blades. These items can be difficult to keep track of, especially surgical needles, so all sharps should be counted as they are added to the sterile tray and/or separated from other instruments on the instrument tray.

Suture packets containing swaged needles can remain unopened and the count is taken according to the label on each packet as some packets contain multiple needles; the scrubbed nurse must verify this count when the packet is opened (Phillips, 2004).

If a needle has broken, both the scrubbed and circulating nurse must ensure all pieces are recovered or accounted for if the surgeon decides not to retrieve a piece; sometimes the risk of retrieving a piece of needle is more hazardous than letting it encapsulate in tissue (Phillips, 2004). The surgeon will make this decision.

General rules

- Leave needles swaged to suture material in their inner folder or dispenser packet until the surgeon is ready to use them

- Give needles to the surgeon on an exchange basis; that is, one is returned before another is passed. Account for each needle as the surgeon finishes with it

- Never let a needle lie loose on the field or Mayo stand. Use needles and needle holders as a unit. The following rule is advised: no needle on the Mayo stand without a needle holder and no needle holder without a needle (Phillips, 2004).

Instruments

Streamlining standardised kits by reducing the number and types of instruments makes counting easier and the head nurse should be informed if unused instruments are routinely included in basic sets. Regularly updated surgeons' preference cards, as well as being a valuable teaching aid for student veterinary nurses, should ensure that all necessary instruments are present; the basic kits can also be augmented with instruments specific to less routine procedures.

Standard count sheets should be included with each basic instrument set, and the person responsible for preparing the set should verify that the initial count is as listed. If the sheet then accompanies the set, the circulating nurse can check the items as they are counted by the scrub nurse.

Conclusion

The consequences of a retained surgical swab or other item will depend on the proximity to vital structures and the degree of associated inflammation and infection. Such consequences however are often severe ranging from further surgery to locate the missing item to life-threatening septicaemia or tumour formation.

While the loss of a swab during a surgical procedure is fortunately not a common occurrence, raising awareness of the potential for occurrence and possible implications of the incidence may reduce the risk even further (Forster et al. 2011). The threat of retained surgical items will always be present, as human error can never be completely abolished, however rigorous adherence to theatre protocols including implementing a consistent routine for managing the surgical trolley, along with the use of effective record keeping and communication skills, should help keep the incidence of retained surgical items to a minimum.

- To answer the CPD questions on this article visit www.theveterinarynurse.com and enter your own, personal login.

- The Veterinary Nurse CPD is approved by Harper Adams University

Key points

- A number of foreign bodies may be inadvertently left in the body after surgery.

- Consequences of retained items are often severe.

- Patients with retained items may present as an acute case or the item may remain latent for a number of years.

- Counting is an accepted practice in order to minimise the retention of foreign objects within the patient.

- Design and rigorous adherence to theatre protocols will help reduce the incidence of retained items during surgery.