All surgical wounds become contaminated by bacteria, but not all become infected. A critical level of contamination is required before actual infection occurs. Quantitatively, it has been shown that if a surgical site is contaminated with >105 microorganisms per gram of tissue, the risk of surgical site infection is markedly increased (Krizek and Robson, 1975). It has been suggested, however, that this figure may over-simplify the situation somewhat, as there are many factors involved in determining whether a level of wound contamination will result in infection, including the host's own level of resistance (Baines et al, 2012).

Bacterial contamination during a surgical procedure can originate from endogenous sources (resident flora of the patient) or exogenous sources (environmental or transient skin contaminants). However the patient is considered the major source of contamination of the surgical wound, with endogenous staphylococci and streptococci reported as frequently cultured organisms from surgical site infections (Baines et al, 2012).

Skin harbours two major groups of microorganisms: transient and residual flora.

Transient flora

Transient or contaminating flora do not normally colonise skin (Gregory, 2005). They are acquired by contact with people/animals or the environment and include organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus, Gram-negative bacteria and yeast (Nicolay, 2006). They are generally easy to remove from the skin through the physical action of scrubbing, and can be almost completely eliminated by effective antiseptics (Baines et al, 2012).

Resident flora

Resident or colonising bacteria such as coagulase-negative staphylococci (e.g. Staphylococcus epidermidis) live on normal skin and help protect it from invasion by pathogenic species (Nicolay, 2006). They have minimal pathogenicity, but may cause infection via a portal of entry made via surgery or other invasive procedures (Gregory, 2005). It is not possible to completely eliminate resident flora from the skin, as approximately 20% of these microorganisms are inaccessible to skin disinfection as they are sequestered in the deeper layers of the skin, among dead skin cells, the hair follicles and sebaceous glands (Warner, 1988; Stonecypher, 2009). As time passes after pre-operative skin preparation, rebound growth of these resident bacteria reaches the surface (Association of Surgical Technologists, 2012). Rebound growth is defined as the tendency of a microorganism to repopulate an area following decontamination, over a much quicker period of time than the original colonisation took place (Scowcroft, 2012). This local bacterial re-colonisation of surgical sites represents a significant risk for wound contamination (Owen, 2007), thus the selection of a skin preparation agent with good residual activity is desirable. Antimicrobial impregnated incise drapes may also help prevent migration of resident microbes into the surgical incision (Association of Surgical Technologists, 2012).

As the majority of surgical site infections (SSIs) are related to pathogens found in the skin, it is essential that the microbial count in the patient's skin is reduced to a minimum prior to incision by using an adequate skin preparation agent. It is well documented that one of the factors that affects the microbial skin count immediately before and during surgery is the skin preparation agent used (Stonecypher, 2009; Bowers, 2012: Silva, 2014). The discussion about which surgical skin preparation agent to use in order to minimise the risk of SSIs has been well debated and researched within both the National Health Service (NHS) and the veterinary profession (Mimoz et al, 2007; Darouiche et al, 2010; Baines et al, 2012), with a combination of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) and 70% isopropyl alcohol (IPA) solutions most widely advocated. It must be noted, however, that the efficiency of cleansing does not depend exclusively on the skin preparation agent used, with the technique of skin solution application now being recognised within NHS literature as an important contributing factor in the fight against SSIs (Silva, 2014).

Historically, the skin preparation pattern taught to both NHS nursing students and veterinary nursing students prior to surgery involves concentric circles. It is a broadly used technique that has been the standard of care for many years, despite there being no documented scientific support for it (Hadaway, 2012). However over the last decade within the NHS this method of skin preparation has been debated, and more recently this technique has been questioned within the veterinary profession also. Studies within the NHS have compared the concentric circles motion technique with a back-and-forth scrubbing technique and suggested that the latter may be more effective and that it is replacing the former (Hadaway, 2012).

To understand the rationale of concentric circle and the back-and-forth techniques as methods to cleanse the skin, it is necessary to understand the purpose of skin preparation and the meaning of both terms.

Surgical skin preparation

The integument is a continuous protective wall covering the entire body, which makes it the largest protective barrier of both the human and animal body and the first line of defence against infection. However the skin is not a flat and simple surface and the situation is further complicated in veterinary patients as animals have numerous hair follicles and may spread bacteria via the oral-faecal route during grooming (Swales and Cogan, 2017). Therefore preparation of the skin before breaking this barrier for a surgical procedure is of the utmost importance.

The purpose of aseptic skin preparation is threefold:

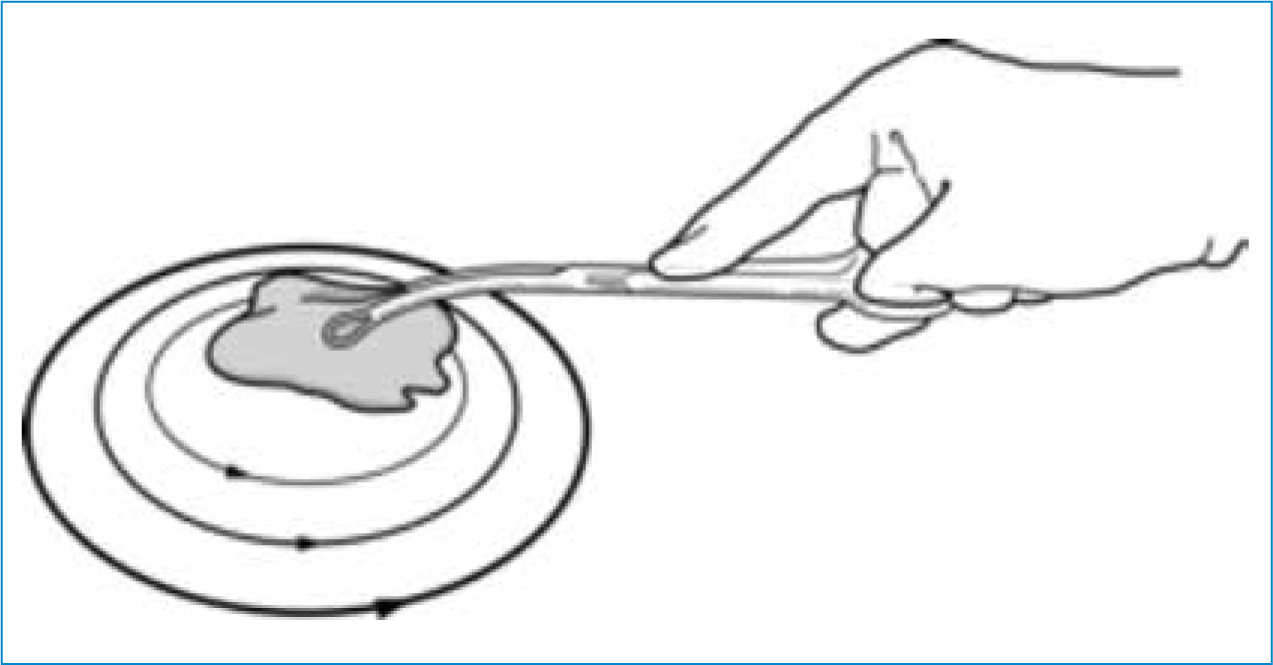

Concentric circles

The concentric circle pattern is frequently used to prepare the surgical site; it resembles a target or bull's-eye (Figure 1). The selected disinfectant is applied at the proposed incision site, working outwards in concentric circles until the outer margins are reached. The disinfectant is left for the required contact time and then removed with lint-free swabs, again working from the centre outwards. The procedure is repeated, usually three to five times, or continued until the skin appears completely clean and the swab yields no dirt. Applying pressure/friction to the skin during this method is not emphasised and is in fact discouraged (Stonecypher, 2009).

Back-and-forth technique

Friction is the force applied between two bodies. Application should be made using lint-free swabs in a methodical back and forth motion to provide friction. Friction, when combined with a back-and-forth technique, was identified by McGrath and McRoy (2005) and Stonecypher (2009) as an important factor in preparing the skin for surgery, and was effective at removing the greater part of the bacterial load which resides in the top dermal layers of the skin. This is further supported in the World Health Organisation (WHO) Guidelines for Safe Surgery (2009) which stated that personnel applying the skin preparation agent should use pressure, because friction increases the antibacterial effect of an antiseptic.

The back-and-forth technique (Figure 2) should commence at the centre of the site to be cleaned maintaining pressure/friction outwardly towards the periphery for 2 to 3 inches over the same area for the duration of the scrubbing time, which is determined by the product used. The procedure should be repeated until the incision site appears completely clean and the swabs yield no dirt.

One of the main arguments in the NHS that may offer the back-and-forth scrubbing technique the advantage over the more traditional method of concentric circles is related to the anatomy of the skin. Skin is composed of 25 layers and studies have demonstrated that around 80% of all skin flora resides within the outer five of those layers (Brown et al, 1989). A study undertaken by Tepus et al (2008) suggested that when a back-and-forth motion was utilised in skin disinfection, this exfoliated the top layers of the skin where most microbes reside, and concluded this likely made it a more effective technique by which microbe counts may be reduced. Tung (2013) concluded that concentrating the surgical preparation at the proposed incision site before moving to the periphery allowed for the preparation solution to reach deeper skin cell layers in this area, leading to a more effective application of antiseptic solution.

Such claims seem to suggest that a back-and-forth motion that covers the same area several times, while creating friction, may be more effective at penetrating skin fissures and crevices and reach deeper cell layers of the skin when compared with the traditional method of concentric circles (Silva, 2014). The rationale for this is that while the latter technique ensures the skin has been painted with a disinfecting solution and is therefore assumed clean, it does not ensure that the same pathway is maintained with each application, thus some areas of skin may not have been effectively cleaned (Stonecypher, 2009). Anderson et al (2013) stated that the concentric circle technique was based on the fundamental principle of aseptic technique, as it helps to avoid contaminants from unprepared areas of skin being dragged onto cleaner areas of skin by the applicator itself. While this principle appears sound and anecdotal evidence would suggest this is the basis for many veterinary personnel adopting this method, Silva (2014) suggested that when preparing the skin using such a concentric circle technique, most of the time utilised during the preparation is spent away from the incision line rather than on it. Silva (2014) further concluded that the incision site was a more likely source of bacterial contamination of the wound rather than the periphery.

ChloraPrepTM

Further support for a back-and-forth application technique comes in the form of ChloraPrepTM which is a single-use, easy to apply, sterile system, containing 2% chlorhexidine gluconate (CHG) and 70% isopropyl alcohol (IPA). Invicta Animal Health Ltd who supply ChloraPrepTM to the veterinary market, advocate the use of the product using a back- and-forth technique rather than the traditional concentric circles method. The recommended contact time for a 2% CHG/70% IPA solution such as that found in ChloraprepTM is 30 seconds with friction. Therefore application should focus on the incision site and immediate surround for 30 seconds prior to covering the peripheral area.

A number of UK hospitals and the Blood Transfusion Service have switched from more ‘traditional’ methods to the use of ChloraPrepTM, and its use, along with the back- and-forth application technique, appears to be gaining popularity amongst veterinary organisations, including The Bella Moss Foundation who advocate the use of a methodical back-and-forth motion in their published guidelines for preparing patients for surgery (http://www.thebellamoss-foundation.com/wp-content/uploads/BMF-ICG-Patient-preparation-for-surgery.pdf).

The wearing of surgical gloves during skin preparation is advisable as it decreases the risk of contamination from the operator's hands; the gloves need not be sterile during the initial stages of the preparation procedure (Baines, 1996), however the use of sterile water or saline, sterile gauze swabs and either sterile sponge-holding forceps or a sterile gloved hand is highly desirable for the final preparation of the patient (Baines et al, 2012).

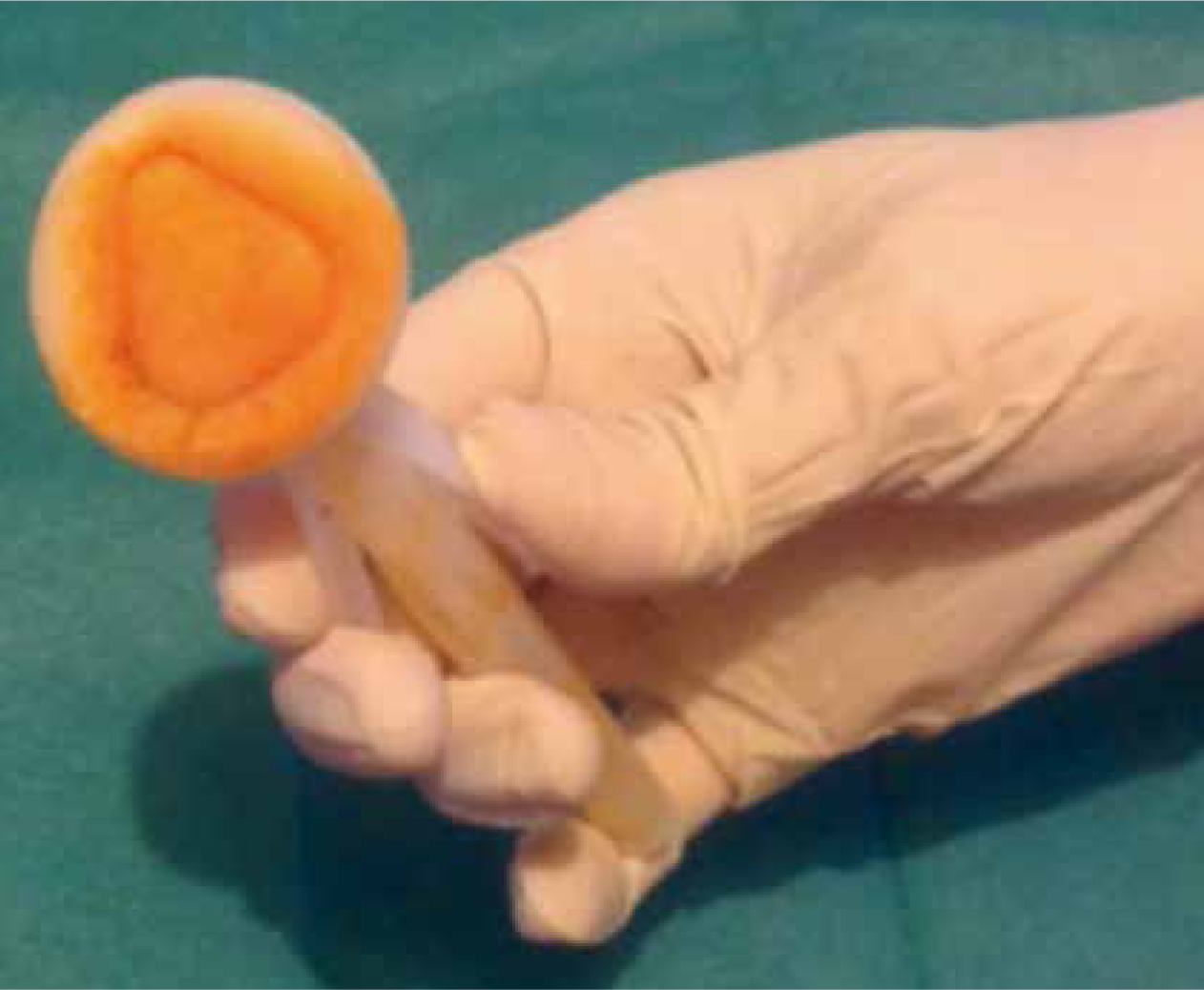

A further benefit of the ChloraPrepTM sterile system is that the patented design ensures a ‘no touch’ technique as users do not come into contact with either the solution or the patient's skin, thus helping to prevent cross-contamination. This is because the pre-mixed solution is contained within an ampoule inside the protective outer applicator, which contains a soft, single-use sponge with which to apply the solution (Figure 3 and 4).

The product is individually packed within a sterile wrapper. The use of a ‘no touch’ technique, or the wearing of sterile gloves, and sterile supplies, is advocated in the WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery (2009).

The back-and-forth technique can of course still be utilised with lint-free swabs and not just the ChloraprepTM system, however as stated above these should ideally be sterile for the final application of skin solution.

Drying time

Whichever technique is used, protocols should ensure that the preparation agent has completely dried by evaporation prior to continuing; 2–3 minutes is usually sufficient for most commonly used agents (Stinner et al, 2011; Barnett, 2014). Drying of the surgical site is important not only to enable sufficient time for the biocidal activity of the agent, but also to prevent strike-through from the resident microflora or from those parts of the patient that have not been clipped or prepared. Strike-through is especially prevalent when fabric drapes are used alone as once wet, they offer no barrier to bacterial transfer (Baines et al, 2012)

So…which technique to use?

There are limited published data to unequivocally support the use of one technique over the other and most of the NHS literature found relates to skin preparation prior to venepuncture and not directly to surgery. Data published by McDonald et al (2001), in which different skin preparation techniques were compared, suggested that a back- and-forth motion technique reduced microbe counts in the skin prior to venepuncture more effectively than did a concentric circle technique, claiming that the latter technique may leave the venepuncture site subject to inadequate disinfection. The difference found in the study, however, was not statistically significant and hence conclusions could not firmly be drawn. Interestingly, an observational veterinary study conducted by Anderson et al (2013) which looked into patient and surgeon preparation in ten animal clinics across Ontario, Canada, identified that skin preparation techniques varied considerably, with both concentric circles, a back-and-forth method and a combination of both methods being observed and different methods employed by staff within the same institution, indicating a lack of standardised protocols. The study confirmed that different application techniques are utilised within both human and veterinary medicine and stated there was insufficient evidence to recommend one technique over the other. However they went on to advocate the use of the concentric circles method, claiming that this method was based on the fundamental principles of aseptic technique as it helped to avoid contaminants from unprepared areas of skin being dragged onto cleaner areas of skin on the applicator. While the authors acknowledged that a back-and-forth technique was commonly observed by veterinary personnel across the clinics, they stated that this practice could potentially be improved through basic staff education and training. However, as skin preparation was only one aspect of this study and of the 148 skin preparations recorded, and as the process was undertaken by multiple staff across ten institutions, one would suggest there are too many variables in order to substantiate such a claim.

A recently published UK veterinary study (Swales and Cogan, 2017) throws the situation into further debate as their findings seem to suggest that the additional friction provided during the back and forth technique offered no advantage over the concentric circles technique and further suggested that the technique used may be that of personal preference, and that there is no observable benefit to the selection of either method. Samples were taken before and after skin preparation in a total of 25 dogs undergoing abdominal surgery; skin scrub methods were changed between patients, alternating between the back-and-forth method and concentric circles, and all skin preparation and sampling was performed by a single person to prevent variability (Swales and Cogan, 2017). Eight of 25 dogs had bacteria present after skin preparation, of which three were prepared using the concentric circle technique and five using the back and forth method. Both skin preparation methods significantly decreased the number of bacteria present on the skin, with no significant differences between the efficacy of either method demonstrated. The sample size used within this study, however, was small as is often the case with veterinary studies, and larger scale studies are required to further support these findings.

Conclusion

Until conclusive studies are presented, it seems reasonable to propose that veterinary personnel follow a skin preparation technique that offers a sound rationale for its use. The NHS literature examined in this article would appear to suggest that a back-and-forth technique should be favoured, as this appears more effective in reaching deeper layers of the skin and reducing the microbial count on the skin more effectively than the still widely used concentric circles motion; however veterinary studies have remained inconclusive. What is certain is that surgical skin preparation is a fundamental component of infection control and the continued prevention of SSIs. Evidence would suggest the mechanical scrubbing action of swabbing alone is not sufficient to remove bacteria; for this reason a suitable solution such as CHG is used as a skin disinfectant, so that the chemical destruction can complement whichever mechanical removal technique is employed (Swales and Cogan, 2017).