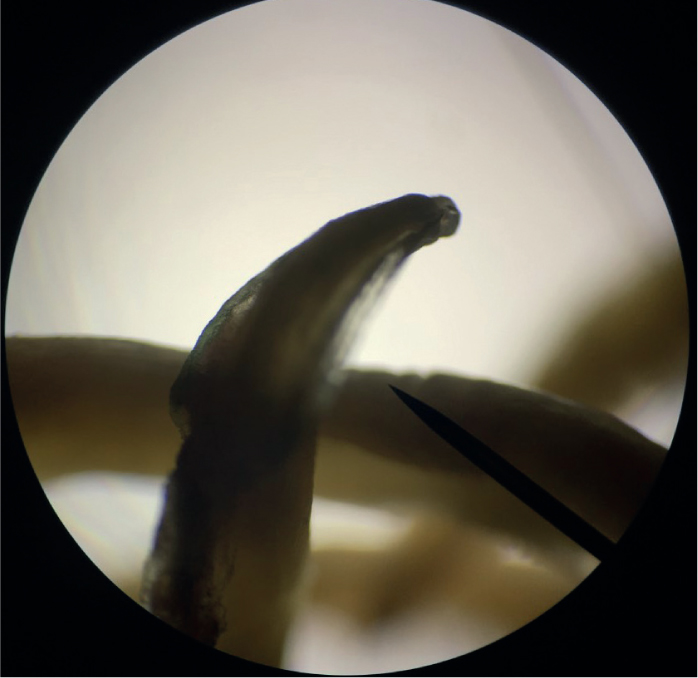

Whether year-round preventative routine deworming regimens for Toxocara spp. (Figure 1) in cats and dogs should be used to reduce zoonotic risk, continues to be a subject of much debate. The European Scientific Council for Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK & Ireland promotes a risk-based approach to parasite prevention and some parasites, such as ticks, tapeworm and lungworm, lend themselves well to this approach. This, however, is not the case for fleas. In 2018, a UK-wide survey found that 28% of cats and 14% of dogs were infested with fleas (Abdullah et al, 2019). These high percentages have animal health implications, with flea allergic dermatitis a common cause of skin disease in cats and dogs, as well as fleas being a cause of human irritation and revulsion. Fleas also have the potential to transmit zoonotic vector-borne pathogens (Figure 2). The same study found approximately 5.7% and 11% of these infestations were positive for zoonotic Rickettsia felis and Bartonella spp. respectively. That means that potentially up to 400 000 dogs and cats in the UK could be carrying fleas positive for Bartonella spp. The elderly and immune suppressed are at particular risk from these zoonoses and are more likely to spend time in their homes with these infestations.

No risk factors have been identified in the UK that make pets more or less likely to be exposed to fleas. The exception is a slight geographical gradient from North to South, but this is not significant enough to prevent unprotected pets from being exposed to fleas over time. Centrally heated homes also allow flea populations to be maintained in homes all year round. Year round flea control is therefore required to maintain both animal and human health. If flea combing is relied on for flea detection before treatment this will allow flea infestations to establish before detection. Once present, flea infestations take months of treatment to eliminate. To prevent flea egg laying and break the reproductive cycle an effective adulticide treatment is required. Adulticides should kill 100% of fleas to prevent egg laying. Adult fleas can lay eggs within 24 hours so effective adulticides must kill fleas within that time.

Potential environmental contamination with flea adulticides is a concern and client education is key to reduce this while treating for pets all year round. Reducing flea treatment frequency will lead to increased household infestation and clients potentially obtaining flea adulticide products online or from supermarkets without any advice on correct application and disposal of packaging or unused product. This is likely to lead to both increased environmental contamination and flea control breakdown. Environmental contamination can be reduced by:

Roundworm

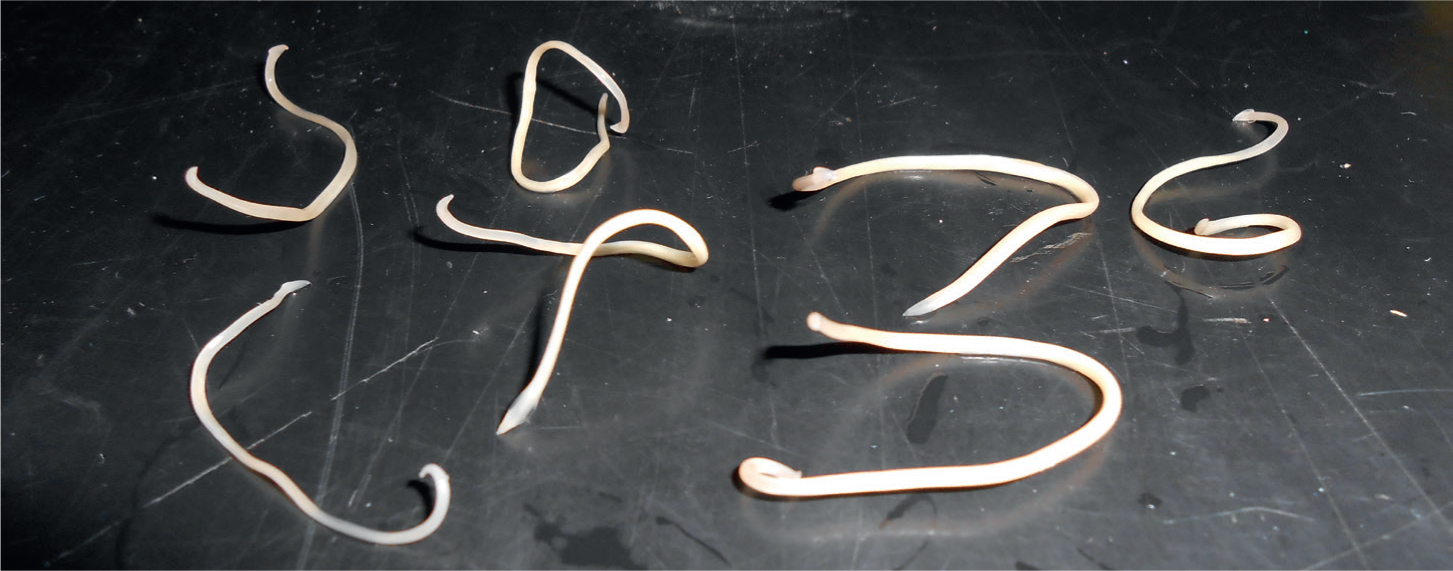

All puppies and kittens are infected with Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati respectively, at or shortly after birth (Overgauuw and Van Knapen, 2013). This occurs through transplacental (puppies) and transmammary (puppies and kittens) infection. At 6 months old, immunity in the host results in elimination of most intestinal infection but arrested stages can remain, leading to intermittent infection with adult worms (Figure 3) and egg shedding throughout a cat or dog's life. In addition, infection can occur through ingestion of paratenic hosts, such as birds and rodents, or though exposure to embryonated eggs in the environment. This results in a wide range of prevalence with approximately 3.5–34% of adult domestic dogs and 8–76% of adult domestic cats shedding Toxocara spp. eggs at any one time if left untreated (Overgaauw and Van Knapen 2013; Wright et al, 2016). These eggs are not immediately infected but contaminate the environment where they can develop to embryonated eggs. Once embryonated they represent a zoonotic risk that if ingested by humans can lead to visceral pain, lethargy, blindness and increased risks of chronic conditions such as asthma, epilepsy and dermatitis.

It has been demonstrated that the use of a licensed anthelmintic every 3 months significantly reduces Toxocara spp. ova shedding and there is no evidence that treating any less frequently than this will have any effect on egg output. Therefore, administration of a suitable product every 3 months should be a minimum recommendation. Coproantigen or faecal flotation can be used as an alternative to this as long as testing is carried out at least 4 times a year and the client understands that shedding of zoonotic life stages may take place in-between testing. Testing alongside treatment is extremely useful, however, as it demonstrates good efficacy and compliance, while also allowing early detection of treatment failure. Monthly treatment will reduce egg shedding by 90% or more and should be considered for cats and dogs on raw, unprocessed diets, those that hunt or those in regular contact with young children or immunocompromised individuals.

Risk factors

Treatment every 3 months for Toxocara spp. infection and routine flea treatment frequently enough to prevent egg laying should be the minimum parasite control recommendation for any cat or dog. In addition, monthly treatment for Toxocara spp. and preventative treatment for ticks, lungworm and tapeworm may also be required based on risk factors the pet is exposed to. These risks and need for additional protection can be assessed by asking a few questions in regard to each parasite.

Monthly Toxocara spp. treatment

Requirement for tick treatment

Requirement for lungworm prevention

Requirements for tapeworm prevention

Compliance factors

Having established which parasites the pet requires preventative treatment for, factors affecting owner compliance or efficacy of the product also need to be considered. Some useful questions to discuss are:

Conclusions

Parasite control is becoming ever more important because of increasing parasite threat and risk of disease to both pets and humans. The veterinary nurse plays a vital role in the education of clients, obtainment of relevant information and client compliance.