Canine visual impairment is commonly presented in first opinion practice resulting from a variety of acute and progressive diseases or trauma. Canine cataracts are one of the most common causes of blindness in dogs (Gould, 2002; Gelatt and Mackay, 2005). Cataracts have a highly variable nature and appearance and can be classified according to their progression, location, age of onset and aetiology (Petersen-Jones, 2002; Fischer, 2019). Owners may report ‘cloudiness’ or opacity of the lens or a grey appearance of the eyes accompanied by gradual or acute vision loss (Figure 1); although, many owners do not realise there are cataracts until very late in the disease process and often believe cataracts are part of the ageing process.

Anatomy and physiology of the canine eye

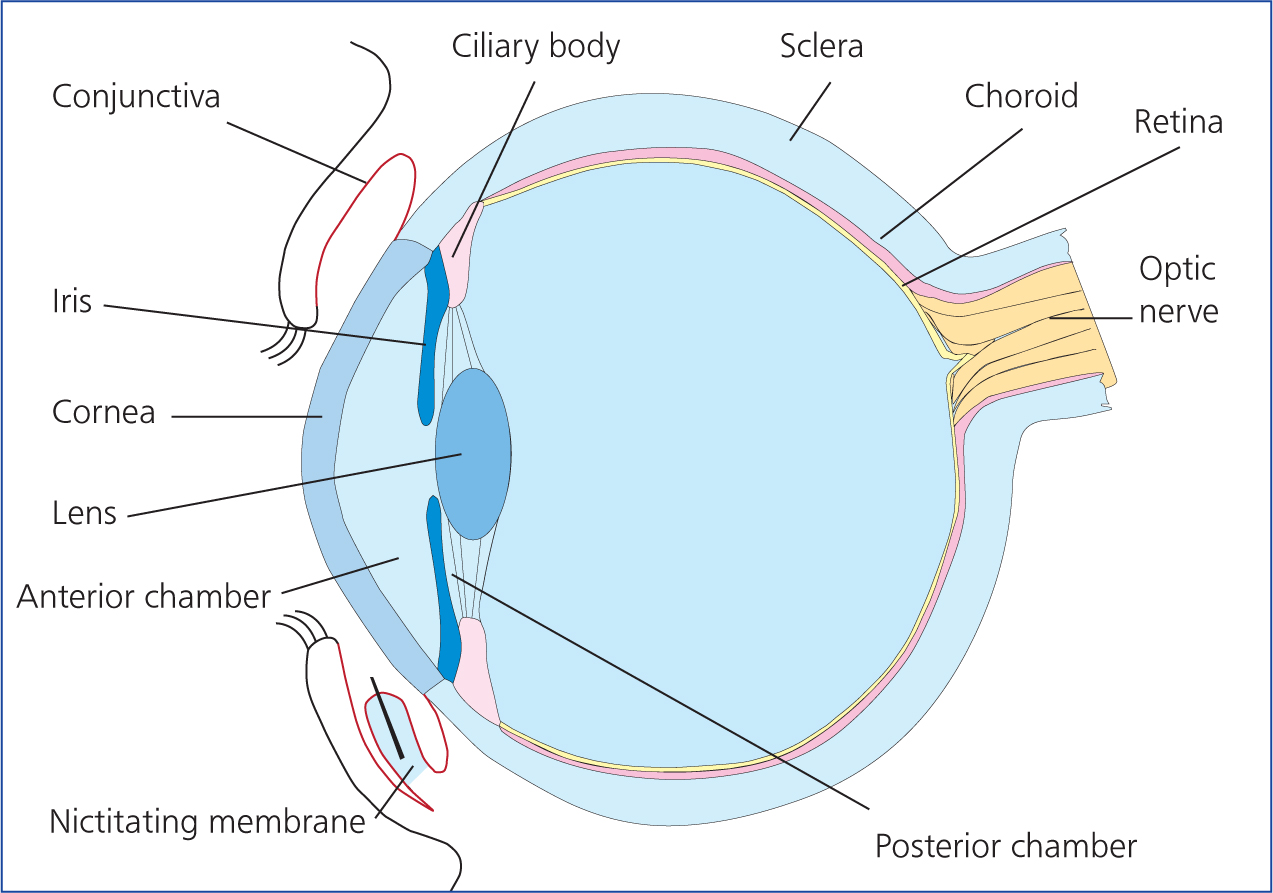

The canine lens is approximately 7 mm thick, 10 mm in equatorial diameter, and has a volume of 0.5 ml (Samuelson, 2013); it divides anterior and posterior segments of the eye and is involved with focusing light onto the retina. The lens is a transparent biconcave structure located behind the iris, surrounded by an outer capsule, supported by the suspensory ligament to the ciliary body (Figure 2). Contraction of the ciliary muscles allows the process of accommodation — the ability of the eye to change the focal length of the lens by changing the curvature of the lens — maintaining focus as the distance of an object from the eye varies (Busse, 2011). The anterior epithelial cells are located beneath the anterior lens capsule and actively divide by mitosis; as they multiply, they move towards the lens periphery and start to form lens fibres (Hyde, 2011). Lens fibres are constantly produced throughout life, resulting in the progressive compression of the lens nucleus. These fibres are partially responsible for the normal ageing change, known as nuclear sclerosis, where the lens nucleus becomes denser (Hyde, 2011). Nuclear sclerosis presents as a grey appearance of the eye however, the retina can still be easily examined (Figure 3).

Formation of a cataractous lens

A cataract is defined as ‘opacity of the lens or its capsule’ of one or both eyes and can be classified by their stage (incipient; immature; mature; and hyper-mature), and by their location (anterior; nuclear; cortical; sub-capsule; equatorial) (Fischer and Meyer-Lindenberg, 2018). Depending on the age of onset cataract formation may also be classified as congenital, juvenile or senile. An opacity of the lens occurs when the thin, clear, highly organised protein fibres that make up the lens of the eye become permanently transformed into opaque proteins (Samuelson, 2013). A cataractous lens will become milky, white and as proteins change throughout the entire lens, a mature cataract develops rendering the dog functionally blind. When the cataract does not involve the entire lens there may be some sight, for example, those not located on the visual axis.

Causes of canine cataracts

The causes of the cataract formation can be genetic, secondary to ocular diseases or as a result of system disease such as diabetes. Other causes could include trauma or toxicity, be age-related, or rarely as a result of radiation or electrocution (Petersen-Jones, 2002; Davidson and Nelms, 2007). Traumatic cataracts may develop because of a thorn or catscratch injury; a lens capsule perforation allows aqueous humor to enter and the lens fibres absorb the fluid, swell and become opaque (Ofri, 2008).

Among these various causes, genetic factors are commonly reported in some breeds including: Miniature Poodles, Yorkshire Terriers, Shih Tzus, Maltese, Golden Retrievers, Boston Terriers, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, Miniature Schnauzers, Standard Poodles and Welsh Springer Spaniels (Rubin et al, 1969; Rubin and Flowers, 1972; Gelatt and Mackay, 2005; Park et al, 2009). The British Veterinary Association (BVA) runs a partnership for ‘The Eye Scheme’, which identifies inherited and non-inherited eye conditions in dogs; the scheme also identifies breeds that are predisposed to hereditary cataracts, congenital hereditary cataracts and progressive retinal atrophy (BVA, 2022).

Cataracts can be formed as a result of secondary progressive retinal atrophy (PRA), a group of hereditary conditions that result in progressive degeneration of the retina and loss of vision (Jeong et al, 2013). Although harder to see than mature cataracts, owners may notice the development of secondary posterior cataracts, which commonly occur in the advanced stages of progressive retinal atrophy (Park et al, 2009; Jeong et al, 2013). Therefore, dogs with PRA-related cataracts often present when the cataracts are mature. PRA is clinically significant when considering cataract surgery, as even if the cataract is treated there may be no improvement in vision. Electroretinography should be performed to determine retinal function before surgery (Turner, 2005) and progressive rod cone degeneration (PRCD) — PRA blood testing may prove beneficial in some cases.

Moreover, cataracts commonly form secondary to canine diabetes (Basher and Roberts, 1995; Beam et al, 1999; Wilkie et al, 2006); up to 80% of dogs develop bilateral cataracts within 16 months of diagnosis (Beam at al, 1999, Wilkie et al, 2006). Pathogenesis of diabetic cataracts is a result of a combination of increased lens membrane permeability, reduced cell membrane function, damage from osmotic effects of accumulating polyols (a group of sugar alcohols), glycosylation of lens proteins, and oxidative injury in human pathogenesis, and it is likely to be the same in canine patients (Kiziltoprak et al, 2019). Hyperglycaemia results in the production of large sugar molecules within the lens, resulting in an osmotic gradient that allows water from the aqueous humor to enter. This process results in rapid irreversible structural change; the swelling of the lens can lead to other complications such as lens capsule rupture, retinal detachment and glaucoma (Kiziltoprak et al, 2019). Early intervention and gradual glycaemic control are essential to reduce complications and promote successful treatment of cataracts; hypermature cataracts and lens capsule rupture often results in lens-induced uveitis (LIU) and increases surgical difficulty.

Effects of cataracts

Canine visual impairment and blindness is usually well-tolerated; dogs have an ability to adapt with minor adjustment to their lifestyle. A previous article discussed the management of visually impaired dogs and the lifestyle adjustments that can be implemented (Foote, 2020). In the author's experience, owners will discuss canine cataracts as a sign of ageing and may not expect treatment to be possible. It is the registered veterinary nurse's (RVN's) and veterinary surgeon's role to discuss the impact and complication of cataract formation. Moreover, acute vision loss, especially the development of diabetic cataracts, can be sudden and therefore disconcerting for all involved. In the author's experience, in both general and referral practice, clients may make hasty conclusions with regards to the treatment options and may wish to discuss euthanasia. Many dogs, however, cope remarkably well with blindness and also with cataract surgery. RVNs should use quality of life assessment tools and good communication skills to reassure owners that, although acute blindness presents abruptly, there may be management options. Hence, a dog presented for acute vision loss should be examined with patience and care; a full ophthalmic examination and a thorough diagnostic approach is vital for these patients.

Complications of cataracts in different stages of development and for different aetiologies have been researched in numerous studies: it is evident that a number of complications can arise (Van der Woerdt et al, 1992, Van der Woerdt, 2000, Adkins and Hendrix, 2005; Plummer et al, 2013). Besides visual impairment, numerous complications can arise as a result of cataract formation including: lens-induced uveitis (LIU); lens instability and lens luxation; glaucoma; retinal detachment; and vitreal degeneration (Fischer and Meyer-Lindenberg, 2018). LIU is intraocular inflammation as a result of the leakage of lens protein material, and is one of the most common complications of cataracts (Van der Woerdt, 1992; Davidson and Nelms, 2007). Ultimately, these complications could lead to a blind and painful eye, which may require enucleation.

Management of canine cataracts

Treatment options for canine cataracts depend on the extent of the cataract, whether they are expected to progress and the effect they are having on the patient. Smaller, incipient cataracts that do not disturb vision may be monitored for signs of progression. Cataracts that are causing visual impairment may be surgically extracted via a procedure known as phacoemulsification. Phacoemulsification is a highly specialised procedure which involves extraction of the cataractous lens from within the lens capsule, through a small peripheral corneal incision(s). The phacoemulsification machine breaks up the lens through high-frequency ultrasonic vibrations and aspiration (Turner, 2005). A synthetic intraocular lens (IOL) may be inserted during this procedure to provide focusing onto the retina; if an IOL cannot be placed, some vision/light detection will be restored with phacoemulsification but focussing ability will be poor.

Mature or hyper-mature cataracts are likely to cause LIU; topical treatment with steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is recommended until surgery, or life-long, to reduce the likelihood of serious complications such as glaucoma (Allbaugh, 2019; Nche et al, 2020). A relatively new treatment that could be implemented is Kinostat™ (Therapeutic Vision), which is an aldose reductase inhibitor that has been shown to reduce the onset or progression of canine diabetic cataracts (Kador et al, 2010, 2019).

Patient considerations for surgery

The veterinary ophthalmologist must ensure that there are no underlying ocular diseases or problems that could affect the outcome of the surgery. For example, concurrent keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS) may increase corneal healing time and predispose the patient to postoperative corneal ulceration (Lim et al 2011). General health screening and routine biochemistry/haematology sampling is recommended prior to the general anaesthetic, and sources of infection/inflammation should be controlled prior to surgery (atopic dermatitis, dental disease).

A critical part of the ophthalmic examination for cataract patients is determining the retinal function. If the retina cannot be examined because of cataract formation, the use of electroretinography should be considered to determine retinal function before surgery (Turner, 2005). As previously mentioned, electroretinography should also be performed to rule out PRA before phacoemulsification. The veterinary surgeon/ophthalmologist will likely perform a pre-operative ocular ultrasound to determine the position of the retina, potential lens rupture or any other abnormal findings such as an intraocular tumour. An ocular ultrasound can be performed conscious at the time of the initial consultation or pre-operation, and most dogs will tolerate this with only a local anaesthetic (proxymetacaine 0.5%).

It is advisable to perform phacoemulsification as early as possible as it carries a better prognosis (Paulsen et al, 1986) and complications such as lens-luxation, glaucoma or retinal detachment could exclude a patient from surgical treatment if allowed to develop (Keil and Davidson, 2001). Therefore, full ophthalmic examination, careful patient selection identification and treatment of underlying medical and ocular complications where possible are recommended to increase the probability of a successful surgical outcome.

The patient's overall health should also be taken into consideration, as this procedure requires a general anaesthetic in veterinary patients, unlike in human patients. Care must be taken with diabetic patients, and ideally they must be relatively stable prior to this procedure. However, as diabetic cataracts are quick to develop, complete glycaemic control may not be possible before the surgery. Notably, topical and system corticosteroids, general anaesthesia and the stress of hospitalisation can further elevate blood glucose levels, so close daily monitoring of the urine and/or blood glucose postoperatively is essential (Gelatt and Gelatt, 2007). The goal for diabetic patients under anaesthesia is not to keep glucose concentrations within a set range, but to avoid intraoperative hypoglycaemia or severe hyperglycaemia (Vukoja, 2019). The brain is the most susceptible organ to episodes of hypoglycaemia — hypoglycaemia is often masked by general anaesthesia as signs generally include confusion, seizures and coma (De Vries, 2011). Therefore, it is essential to monitor blood glucose levels at regular intervals during the perioperative period. Although, mild hyperglycaemia is preferable to hypoglycaemia under general anaesthesia, it should be monitored and controlled where possible as hyperglycaemia is associated with surgical site infections, dehydration and electrolyte loss (American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA), 2018; Vukoja, 2019).

The general behaviour of the dog should also be considered, and the RVN may wish to discuss handling and management of fractious or highly excitable patients pre-operatively. Fractious, aggressive or excitable dogs can be difficult to medically manage and the postoperative application of drops can be difficult. The RVN could implement topical drop training for the owner and patient before surgery, with a lubricating drop. Gentle and efficient handling during application of drops is essential to reduce stress and complications. Anxious, aggressive or difficult to handle patients are at an increased risk of complications, especially if they are restrained incorrectly or are able to self-traumatise. Examples of patient-related complications include, hyphema, surgical wound dehiscence and uveitis (Gelatt and Gelatt, 2007). If the owner or RVNs are unable to manage medications or monitor intra-ocular pressure (IOP), serious complications may occur and may not be promptly identified, such as a postoperative increase in IOP which would render the surgery non-beneficial. Owners can monitor for signs of an increased IOP by monitoring for signs of pain, such as increased interference and blepharospasm and for changes in vision, such as a poor menace response or bumping into the home surroundings.

Phacoemulsification: pre-operative care and surgical preparation

RVNs can play a critical role in the surgical management of canine cataracts from admission through to peri-operative care and owner education. This includes recognition of complications, providing aftercare and long-term management. During admission, a thorough history should be taken — it is useful to collect information about the patient's usual diet, time of feeding, allergies, normal routines and any concurrent conditions or medications. At the time of admission, it is also advisable to remind the owner of the intensive medication regimen that is required postoperatively, and to ensure that the home environment is suitable for recovery. General anaesthetic risks should be discussed as well as the potential risks of phacoemulsification including infectious endophthalmitis (introduction of bacteria to the eye during surgery), postoperative ocular hypertension, corneal lipid deposition, corneal ulceration uveitis, intraocular haemorrhage, retinal detachment and glaucoma (Klein et al, 2011; Ledbetter et al, 2018). Postoperative ocular hypertension and potential glaucoma is a priority for discussion, as postoperative glaucoma may result in enucleation if it cannot be controlled.

Depending on practice protocol, the patient may be admitted the day before surgery — this is especially helpful for diabetic patients for blood glucose monitoring, feeding and insulin administration before the general anaesthetic (Woodham-Davies, 2019). Ideally, diabetic patients should be operated on early in the day so that postoperative ocular hypertension can be identified and managed within the working day.

Phacoemulsification: intra-operative care

Each patient should be assigned an American Society of Anaesthsiologist (ASA) status grade before the general anaesthetic, to help the surgical team predict and prepare for peri-operative complications (Portier and Ida, 2018). The use of a surgical safety checklist can also prove invaluable for tracking patient details, implementing teamwork and reducing patient morbidity rates (Ebeck, 2022). A number of topical drops may be applied prior to pre-medication, including lubricants and anti-inflammatories. Mydriatics may also be applied as it is difficult to achieve maximum mydriasis after induction (Gross and Pablo, 2015).

RVNs play a key role in infection control as they often take part in surgical skin preparation. When preparing for any ocular surgery, there are several nursing considerations because of the sensitivity and fragility of ocular structures. RVNs should wear appropriate personal protective equipment before surgical skin preparation to limit contamination of the surgical area. The ophthalmologist will often opt to not clip the surgical site as this often causes further irritation and patient interference post-operation (Woodham-Davies, 2019). However, it is advisable to trim the surrounding peri-ocular fur of long-haired breeds with curved lubricated scissors, as this will aid cleaning and hygiene maintenance post-operation. A topical lubricant should be applied to the eye before clipping or trimming to prevent hairs contaminating the ocular surface. Adhesive drapes may also prove beneficial to prevent hairs entering the surgical site.

For surgical preparation, povidone-iodine is the preferred solution, diluted 1:50 in sterile saline. This can be done by adding iodine to a bag of sterile saline, then drawing up the solution into syringes for use on the conjunctival sac and cornea (Peterson-Jones, 2002). A luer-lock syringe of the 1:50 iodine solution can be used with sterile cotton buds to clean the conjunctival sac and cornea. Care must be taken to avoid using povidone-iodine hand scrub solutions as they contain additional detergents, which can cause corneal or conjunctival ulceration. A higher concentration of 1:10 can be used on the external eyelid skin. Lint-free swabs should be used rather than linting versions or cotton wool, which can leave particles on the surgical site. It is also important to ensure that the correct contact time and dilution is achieved for maximum antisepsis; both factors are often overlooked in busy veterinary surgery (Adshead, 2012). The RVN may be the surgical scrub nurse during the phacoemulsification, and confidence with closed gloving techniques, maintaining sterility, identifying ophthalmic instruments and knowledge of the phacoemulsification procedure are vital. Equipment and ophthalmic instruments often need setting up pre-operatively, which a surgical scrub or circulating nurse may be involved with.

Phacoemulsification patients can be challenging to monitor during anaesthesia because of the limited access to the ocular reflexes, jaw tone and mucous membranes (Presnail, 2016). Patient positioning and surgical draping limit accessibility to the patient, and monitoring equipment, such as an oesophageal stethoscope and a multiparameter monitor, is essential. Multiple intravenous (IV) catheters may be useful for continued glucose monitoring — ideally a saphenous IV catheter should be place for access during the anaesthetic. Neuromuscular blocking agents are often used for phacoemulsification to relax the ocular muscles, however, these also relax the respiratory muscles and mechanical ventilation is essential. The use of a nerve stimulator is recommended when monitoring the muscular blockade alongside a ventilator.

Postoperative and home care

The prognosis after cataract surgery is very good, and success rates are approximately 90% (Lim et al, 2011, Krishnan et al, 2020). Although surgical complications are rare, some potential complications (Sigle and Nasisse, 2006; Lim et al, 2011) could occur such as:

- Retinal detachment

- Endophthalmitis

- Glaucoma.

Ocular hypertension is common immediately post-operation as a transient increase in pressure is common, and IOP measurements should be taken at regular intervals. Alongside, monitoring IOP, RVNs are often involved in administering topical drops, managing diabetes and continued postoperative care.

Phacoemulsification itself involves intensive aftercare including frequent topical eye drops and regular re-examination appointments. Often, patients are kept for 24 hours after the operation to monitor for postoperative ocular hypertension, although, it is possible for patients to be discharged in the evening with a planned re-examination the following morning. Generally, exercise must be limited to lead-only walks for up to 6 weeks, and the length of off-lead walks should be determined by the veterinary surgeon during re-examinations to assess the IOL stability. Care should be taken with toys, and head shaking should be avoided to reduce the risk of inflammation. Long-term monitoring is advised to maximise the chances of a good outcome and to allow the early identification and management of any post-operative complications.

The surgeon may opt to operate on one or both eyes during the pre-operative check or during surgery, with the view that the remaining eye may have some limited vision, if postoperative complications occurred in the operated eye. However, the risk of LIU and associated complications would still remain for the cataractous eye. Often, phacoemulsification is performed bilaterally to reduce hospitalisation and anaesthetic time, and so both the patient and owner only goes through the recovery period once. Surgery is considered to have failed when dogs develop painful and/or blinding complications such as endophthalmitis, retinal detachment or glaucoma (Sigle and Nasisse, 2006). The long-term success rate of phacoemulsification is considered high, at approximately 90% after 1 year (Klein et al, 2011, Krishnan et al, 2019). The prevalence of glaucoma has been shown to increase with time, although it remains under 10% until after the 1 year follow-up period. Regular re-examination and IOP monitoring is vital during the first-year post-operation (Klein et al, 2011).

Medical management

Medical management of a cataractous eye aims to maintain comfort for the patient, as often vision cannot be restored without surgery. Medical management may include topical eye drops, such as anti-hypertensives and anti-inflammatories, alongside oral medication such as, NSAIDs. A lower success rate/higher incidence of painful eyes in dogs receiving medical therapy is to be expected and secondary glaucoma has been found to occur more frequently in cataractous eyes than those that have undergone phacoemulsification (Lim et al, 2011). However, if surgical management is deemed to be unsuitable, for example because of age, general anaesthetic risks or PRA, medical management can be considered. RVNs often take part in client education, administering medication and discussing quality of life. Despite medical intervention, cataractous eyes can still become glaucomatous and enucleation may be deemed necessary. The owner must be made aware that cataracts cannot be removed or ‘dissolved’ with topical eye drops, and that effectively they are treating a blind eye that has the potential to become glaucomatous and painful.

Conclusion

Cataract surgery is a delicate procedure that requires a thorough patient assessment, owner compliance and can carry a degree of risks, however, it often proves a very worthwhile procedure for both patient and owner. Phacoemulsification requires specialised equipment, anaesthetic protocols and knowledge of pre and postoperative complications. Although not all RVNs will be involved with cataract surgery, because of the prevalence of canine cataracts, the knowledge of their pathophysiology and management is essential for client education and for referral advice.

KEY POINTS

- Canine cataracts are a common condition that must be assessed and treated in a timely manner to prevent further complications.

- Registered veterinary nurses can be well utilised in a variety of ways in cases of canine cataracts.

- Client education is vital for the management of canine cataracts and the prevention of lens-induced uveitis.