Neoplastic disease affecting respiratory function is anecdotally encountered more rarely in small mammal species. Early recognition can be challenging in prey species as clinical signs may be mild for most of the disease process until the animal is severely compromised. Similarly, diagnosis can be more challenging in small mammals as a result of factors such as owner finance and compliance leading to restraint of diagnostic modalities. This article will explore clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment options and nursing interventions associated with thymomas in rabbits.

What is a thymoma?

The thymus is the first of the lymphoid organs to be formed during embryonic development. As in other mammals, the rabbit thymus provides the body with the T-cell population of lymphocytes. In most mammals the thymus regresses during ageing into adulthood as production of lymphocytes is dominated by other immune tissues (Harris et al, 2015).

In the rabbit, the thymus remains large throughout life and lies cranioventral to the heart, extending into the thoracic inlet. It is visible on normal thoracic radiographs. Tumour formation originates from abnormal epithelial cell division. Tumours of the thymus can be malignant (malignant thymoma or thymic carcinoma/lymphoma) and metastasise to other organs causing systemic disease. However, usually in rabbits thymomas behave in a benign fashion. This means they are slow growing and rarely metastasise out-with the thoracic cavity, but can be locally invasive and may cause pleural dissemination (Morrisey and McEntee, 2005).

The incidence of thymomas in rabbits is reported to be approximately 8% in a study of 55 rabbits with neoplasia (Greene and Strauss, 1949). However, most literature relating to incidence is now outdated and further work is required to establish the true incidence of this neoplasm in the current domestic population. Although the condition appears to occur rarely, Kunzel et al (2012) reported that in a study of 13 rabbits presenting with mediastinal masses all 13 were diagnosed with thymomas.

Clinical signs

Presenting to practice often relies on owners perceiving a problem. Unfortunately for small mammals, the instinct to hide signs of illness often means these animals will present to a veterinary surgeon in a compromised state because of a delay between onset of disease and a problem being recognised. In humans it is reported up to two-thirds of people are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. When present, clinical signs usually include chest pain, a cough, phrenic nerve paralysis, dyspnoea and superior vena cava syndrome (Rajan and Giaccone, 2008). These symptoms mirror those seen in rabbit patients, although the symptoms may be expressed differently. For example, chest pain can result in intermittent periods of gut stasis/anorexia. Coughing is a rare presenting clinical sign in rabbits (in comparison to sneezing) in the author's opinion because it is often not perceived. Rabbit coughs are soft, quick and often inaudible allowing for this clinical sign to be missed. Literature surrounding phrenic nerve damage in rabbits as a result of large thymoma size displacing/damaging the nerve could not be found in relation to pet rabbits. However, this phenomenon is well described in human medicine. Phrenic nerve damage can result in severe dyspnoea as paralysis of the hemidiaphragm causes paradoxical upward movement during respiration (El-Masri et al, 2018). Typically, dyspnoea associated with thymoma in rabbits is attributed to the presence of a space-occupying mass. However, it is possible that phrenic nerve damage also plays a part in this disease process as anatomy and physiology of phrenic nerves is largely similar between mammals. Rabbits have been used as study models for unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis by surgical resection of phrenic nerve roots (Marie et al, 1997). As rabbits largely rely on diaphragmatic movement for respiration it seems likely this would cause severe respiratory issues, however further research must be done in this area to confirm such claims.

Dyspnoea more commonly results from a sizeable mass occupying space in the mediastinum. In a study of 13 rabbits, the most common clinical sign reported in rabbits diagnosed with thymoma was dyspnoea (76.9%) (Kunzel et al, 2012). This was followed by exercise intolerance (53.9%) and bilateral exophthalmos (46.2%). Dyspnoea in rabbits may result in tachypnoea, nasal flaring, an orthopneic body position and in very severe cases open-mouth breathing. Clinical examination may reveal dulled/muffled heart sounds, cardiac murmurs, cyanotic mucous membranes, poor pulse quality and reduced chest compliance. Nasal twitches are not related to respiration in rabbits and should not be used to count respiratory rates.

Exercise intolerance may be difficult to assess in rabbits, particularly if kept in confined outdoor spaces such as hutches. Fortunately for rabbits, education regarding husbandry and need for space has improved greatly: many rabbits now live in close quarters with their owners and/or have access to large pens outside. This allows increased opportunity for owners to observe rabbits' daily routines and energy levels.

Bilateral exophthalmos may be one of the more visible clinical signs. Typically, this tends to worsen with ventro-flexion of the head and protrusion of the nictitating membrane is common. This clinical sign is a result of compression of the vena cava, which results in impeded drainage from the orbital venous system which allows blood to pool in the large retrobulbar venous plexus (Maini and Hartley, 2019). Some rabbits may develop mild exophthalmos and a visible nictitating membrane when very stressed, and intact male rabbits can also develop this during the breeding season; this clinical sign is unique to rabbits but not pathognomonic to thymoma (Figure 1).

Paraneoplastic syndromes have been documented in a range of species and sebaceous adenitis can be associated with thymomas in rabbits. Histopathologically, sebaceous adenitis is similar to that seen in dogs. However, it is often likened clinically to thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis in cats because it is seen more commonly in association with systemic disease (Hess and Tater, 2012). Rabbits present with non-pruritic, scaly, flaky dermatitis that usually begins around the face and neck. This condition can also be seen in cases of hepatitis but association with respiratory signs raises suspicion of thymoma. Treatment is rarely successful, however, there are reports of success using ciclosporin, acitretin, pentoxifylline and treating underlying disease (Hess and Tater, 2012).

Diagnosis (non-invasive)

Diagnosis is achieved by a veterinary surgeon through a variety of means. Clinical history and examination fitting with the above should raise the suspicion index for thymoma, and prompt further investigation, which nurses will usually be involved with. It is important to remember these animals are compromised, so reducing stress and providing oxygen in a stress-free manner is invaluable. Anaesthesia and sedation for these patients is outside the scope of this article, however veterinary surgeons and nurses should familiarise themselves with safe protocols for rabbits with respiratory compromise.

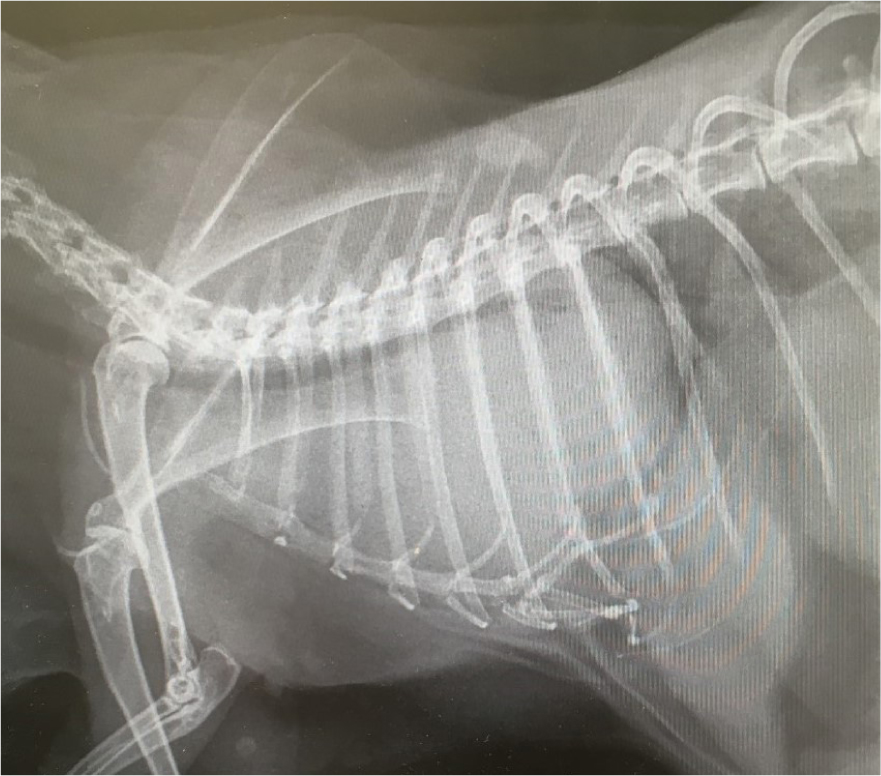

Radiography

Diagnosis via this method alone is often tentative unless the mass is very large. Lateral x-rays are often requested by the veterinary surgeon and reveal a mass in the cranial mediastinum. The trachea and heart are often displaced (Figure 2). Some animals may allow for conscious radiography using the ‘bunny burrito’ method, gentle handling and oxygen therapy if dyspnoeic.

Ultrasonography

A thoracic-focused assessment with sonography for trauma, triage, and tracking (T-FAST) scan of the thorax can be used to evaluate thymus consistency and its effects on the heart and pleural space. Some thymomas have large cystic compartments and temporary relief can be gained by draining this fluid (Morrisey and McEntee, 2005). Pleural effusions can also be drained if they are diagnosed concurrently. The use of quiet clippers in a stress-free environment is advised to prepare the animal for ultrasonography.

Computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging

Computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging is considered gold standard for evaluation of mass size, consistency and assessment of infiltration into other tissues. It will usually be used when planning for surgery or targeted radiotherapy. However, as with other imaging it does not distinguish between different neoplasms or the grade of their malignancies.

Fine needle aspirate

This is performed by a veterinary surgeon, usually in a sedated animal with guided by ultrasound to avoid important structures in the thorax. In human medicine controversy exists over the usefulness of this procedure as there is often a large population of obscuring benign lymphocytes and diagnosis requires both a population of epithelial cells and lymphocytes (Wakely, 2008). Thymomas are commonly cystic and do not exfoliate well, further complicating the usefulness of this test. However, in rabbits where more invasive methods of confirming diagnosis (tissue biopsy) are not feasible/indicated this might be the clinician's method of choice. Nurses can clip and prepare patients, conscious where feasible, and place intravenous catheters with guidance to reduce the animal's time under sedation/anaesthesia and improve patient safety. Monitoring of these patients under sedation should be intense.

Blood sampling

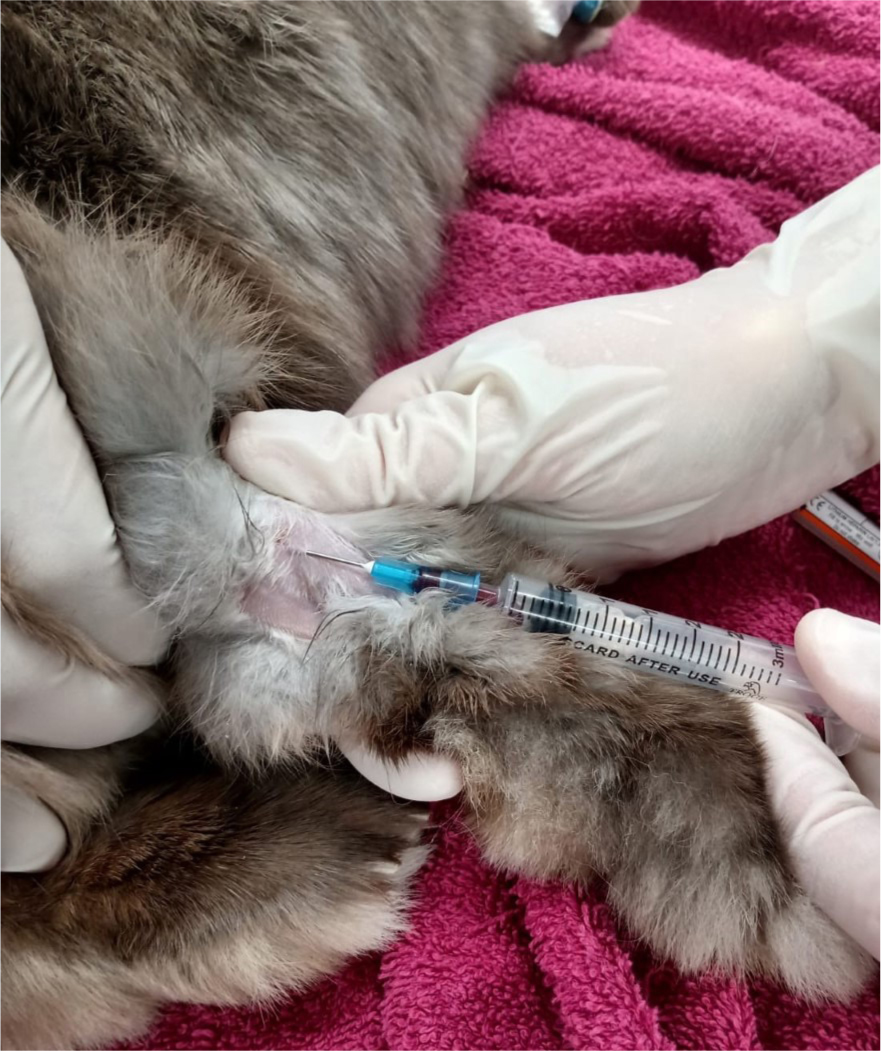

As this is generally non-invasive and easy to achieve in rabbits, blood sampling is likely to be requested by a veterinary surgeon before treatment. Heterophilia with monocytosis, thrombocytosis, eosinophilia and basophilia has been described in one rabbit. In two other cases, white blood cell counts were 42 000 and 18 000/μl, with more than 70% lymphocytes (Huston et al, 2012). Blood reports can also high-light other concurrent disease processes, which may influence the veterinary surgeon's treatment strategies. Jugular samples should be avoided in patients with respiratory compromise as restraint around the head/neck may worsen clinical signs. The lateral saphenous vein is the author's site of choice when blood sampling rabbits under direction as, generally, large volumes can be sampled with minimal stress to the patient (Figure 3).

Treatment

Treatment options for rabbits with thymoma are largely anecdotal and based around treatment for other species. However, success has been reported (Guzman Sanchez-Migallon et al, 2006), and more commonly advanced imaging methods are available to rabbit patients allowing clinicians to offer a tailored treatment plan to each patient.

Surgery

Where there is a benign solitary mass, surgical excision is the treatment of choice (Morrisey and McEntee, 2005). Surgical excision of thymomas in rabbits has been completed successfully but there is a high risk of complication and acute perioperative mortality. A median sternotomy is often the preferred approach as this gives optimum visual and surgical access (Morrisey and McEntee, 2005). Ideally CT imaging will have been performed before surgery so meticulous surgical and anaesthetic planning can be implemented. Often these cases are complex and sternotomies are usually performed in specialist referral centres. Nurses assisting with these cases must be highly experienced, both in the monitoring of open chest surgeries and the needs of rabbit patients during anaesthesia and postoperatively. Excellent pain management and recognition of pain is para-mount should these surgical cases be successful.

Chemotherapy

Unfortunately for rabbits, immunosuppression of any kind may exacerbate common underlying pathologies such as Encephalitozoon cuniculi. In a study by Horváth et al (1999), rabbits were intraperitoneally infected with spores of E. cuniculi and then treated with cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg first dose, then 15 mg/kg weekly during the 12-week experimental period). In these rabbits, clinical signs of encephalitozoonosis developed between weeks 4 and 6 and all died during week 6. No signs of infection were seen in either positive or negative control rabbits indicating cy-clophosphamide (commonly used in chemotherapy protocols in other species) may give rise to a potentially fatal E. cuniculi flare. Serology testing for this condition is advised before beginning chemotherapy protocols in rabbits and protocols should be tailored to the patient with advice from a certified oncologist.

Radiotherapy

Thymoma's are radiosensitive and radiotherapy has been used successfully in dogs, cats, rabbits and humans. As a result of proximity to vital structures (heart and lungs) the patient is at risk of radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis. Radiotherapy can be used to offer palliative care to animals who are poor surgical candidates. More promisingly, a study by Dolera et al (2014), has documented the use of intensity-modulated radiotherapy in 15 client-owned rabbits. All rabbits showed complete tumour regression by day 40, and at year 1 and year 2 post-treatment no rabbits had suffered mortality or morbidity associated with intensity-modulated radiotherapy.

In 2012, Andres et al, found that median survival time for rabbits that survived the first 2 weeks of mega voltage radiotherapy was 727 days, further supporting the use of RT to prolong life in rabbits with thymoma. On balance, no literature could be found confirming median survival time in rabbits with no treatment but, typically, these patients present in a decompensated state and it seems reasonable to presume survival time would be lower.

Nursing interventions

Holistic nursing interventions are required for greater success with rabbit patients. As obligate nasal breathers many rabbits in respiratory distress will become very anxious. While care for thymoma certainly involves diagnostic tests and treatments prescribed by a veterinary surgeon, nurses can also provide the animal with invaluable therapeutic care that can directly affect the clinical outcome. Based on a nursing ability care model, considerations for rabbit patients with thymoma are described in Table 1.

Table 1. Nursing care plan for a rabbit with a thymoma

| Action | Potential problem | Proposed nursing care |

|---|---|---|

| Eating | Patient may have secondary ileus/reduced appetite because of chest pain/dyspnoea | Ensure all medications prescribed by the veterinary surgeon (VS) are given on time and depending on stress/respiration it may be preferable to give injectable forms vs oral. Rabbits with reduced appetite should be offered familiar palatable items such as herbs/dandelions. Ensure adequate analgesia by regular pain scoring. Provide a high-quality high-fibre diet |

| Drinking | Increased respiration and effort increase fluid requirements — dehydration may also be secondary to ileus | Administer fluid therapy set by VS. Rabbits with cardiac abnormalities may be at increased risk of fluid overload. Increase monitoring of respiratory rate and auscultate chest regularly. Large volumes of fluids per os is inadvisable |

| Urination | Thymoma should not directly influence urination, however, the use of diuretics in patients with concurrent pleural effusion may increase urination | Many rabbits are litter trained and often will not void until a suitable area is provided. Ensure a litter tray/toilet area with appropriate material is provided |

| Defecation | This may be decreased in animals with secondary ileus/stasis | As above, provide a litter area. Ensure any gastrointestinal motility agents prescribed by VS are delivered on time. Count faeces twice daily and remove in between to objectively assess improvement. Ensure adequate analgesia with regular pain scoring |

| Breathing | Breathing is likely to be compromised | Oxygen therapy can be delivered in an oxygen tent for a hands-off approach. Provide a hide/place towels over tent to reduce stress. Flow by can be provided but face masks in conscious rabbits are generally poorly tolerated. Keep away from predators/noise. Ensure adequate analgesia and intensely monitor respiratory rate/depth/pattern |

| Temperature | Severely compromised animals may be hypothermic | Ensure normothermia — Bair Huggers, heat pads, incubators can all be utilised. Ensure not to overheat as this may worsen dyspnoea. Once temperature stabilised and heating removed ensure temperature is taken again at another interval to assess relapse |

| Grooming | Coat may be unkempt | Dyspnoeic animals may groom less. If the rabbit enjoys brushing/grooming this can be attempted but is generally not a priority for these patients |

| Mobility | Mobility may be reduced as a result of exercise intolerance/breathlessness | Ensure the patient has enough room to mobilise but provide multiple hides for resting. While exercise is generally good for most conditions, over exertion may worsen dyspnoea |

| Sleep/rest | Dyspnoea may prevent sleep/rest | Aim to alleviate clinical symptoms of dyspnoea. Provide oxygen where relevant. VS to perform thoracocentesis where appropriate, etc |

| Express normal behaviour | Difficult in a hospital setting | Provide correct husbandry, allow time out of enclosure, provide correct diet etc |

Conclusion

Thymoma in rabbits is a slow growing neoplasm that can affect the rabbit's quality of life. Improvements in medicine and surgery allow owners more advanced therapeutic options for their pet. Nurses provide invaluable care to exotic patients and a knowledge of a range of conditions seen in these species can improve clinical decision making in practice and allow for more in depth clinical discussions. Improved knowledge in specialist areas may also help to accelerate standards of rabbit welfare and nursing.

KEY POINTS

- Thymoma in rabbits is a neoplasm found in the cranial mediastinum.

- Common clinical signs are bilateral exophthalmos, dyspnoea and exercise intolerance.

- Diagnosis is usually achieved through clinical signs, advanced imaging and tissue biopsy.

- Treatment options include palliative care, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.