Dog and cat health can be threatened by several parasitic diseases caused by intestinal and cardiorespiratory helminths and vectorborne pathogens. A plethora of antiparasitic products is available on the market and several broad spectrum parasiticides allow the control of both endoparasites and arthropod vectors of dogs and cats. Thus, an all-round knowledge of the biology of parasites and their vectors is pivotal to choose and use these molecules properly.

Intestinal helminthes

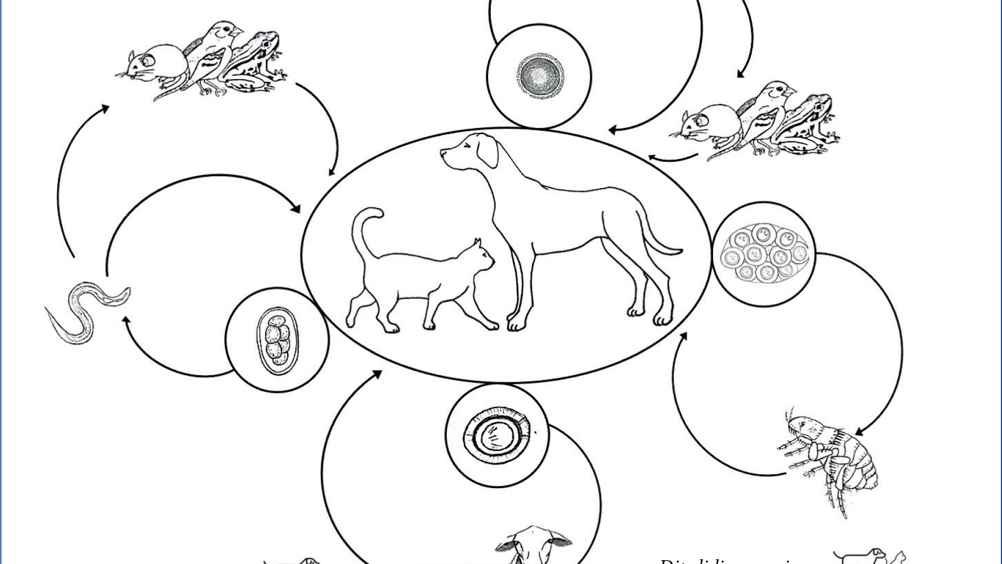

Intestinal helminthes of companion animals are of primary importance in daily clinical practice (Figure 1). The roundworms (ascarids), Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati (Figure 2), infecting dogs and cats respectively, are the most common intestinal parasites of dogs and cats worldwide (Overgaauw, 1997; Epe, 2009; Traversa, 2012), while Toxascaris leonina (infecting both dogs and cats) is less distributed. Vertical transmission, resistance of the eggs in the environment, number of eggs produced by adult females and availability of paratenic hosts, are a winning strategy for the spread of ascarids. Adult animals suffer from intestinal distress, while puppies and kittens also show ‘pot belly’, poor growth, vomitus and/or diarrhoea with frequent expulsion of adult worms still alive and viable. Heavy infections cause potentially fatal occlusions, intussusceptions and perforations (Epe, 2009). Ascarids represent a threat to humans, who become infected by ingesting Toxocara larvated eggs from the environment. Especially in children, Toxocara spp. causes the so-called visceral, ocular and cerebral larva migrans syndromes (Robertson and Thompson, 2002). Numerous green areas and playgrounds in suburban and urban contexts are highly contaminated with roundworm eggs, which become infective from 2–6 weeks after their emission in the environment (Traversa et al, 2014).

Hookworms are bloodsucking intestinal nematodes distributed worldwide. The lifecycle of canine and feline hook-worms presents varying patterns of transmission, based on the high fecundity of adult females, the galactogenic transmission, the ability of larvae to penetrate the skin and/or mucosae, and the availability of paratenic hosts (Epe, 2009; Traversa, 2012). Larvae and adults of Ancylostoma caninum (affecting dogs), Ancylostoma tubaeforme (affecting cats) and Uncinaria stenocephala (affecting both) damage the mucosa of the small intestine and suck blood, leading to anaemia, melaena, diarrhoea and weight loss, with possible fatal outcome, especially in heavily infected young animals. Ancylostoma caninum larvae can penetrate human skin causing localised papules and pustules, while the ability of A. tubaeforme and U. stenocephala to cause disease in humans is still debated (Bowman et al, 2010; Traversa, 2012). The serpiginous tracks caused by cutaneous larva migrans are more often reported in travellers returning from areas where Ancylostoma braziliense is endemic, while the role of A. caninum in this syndrome is still to be definitively clarified (Bowman et al, 2010).

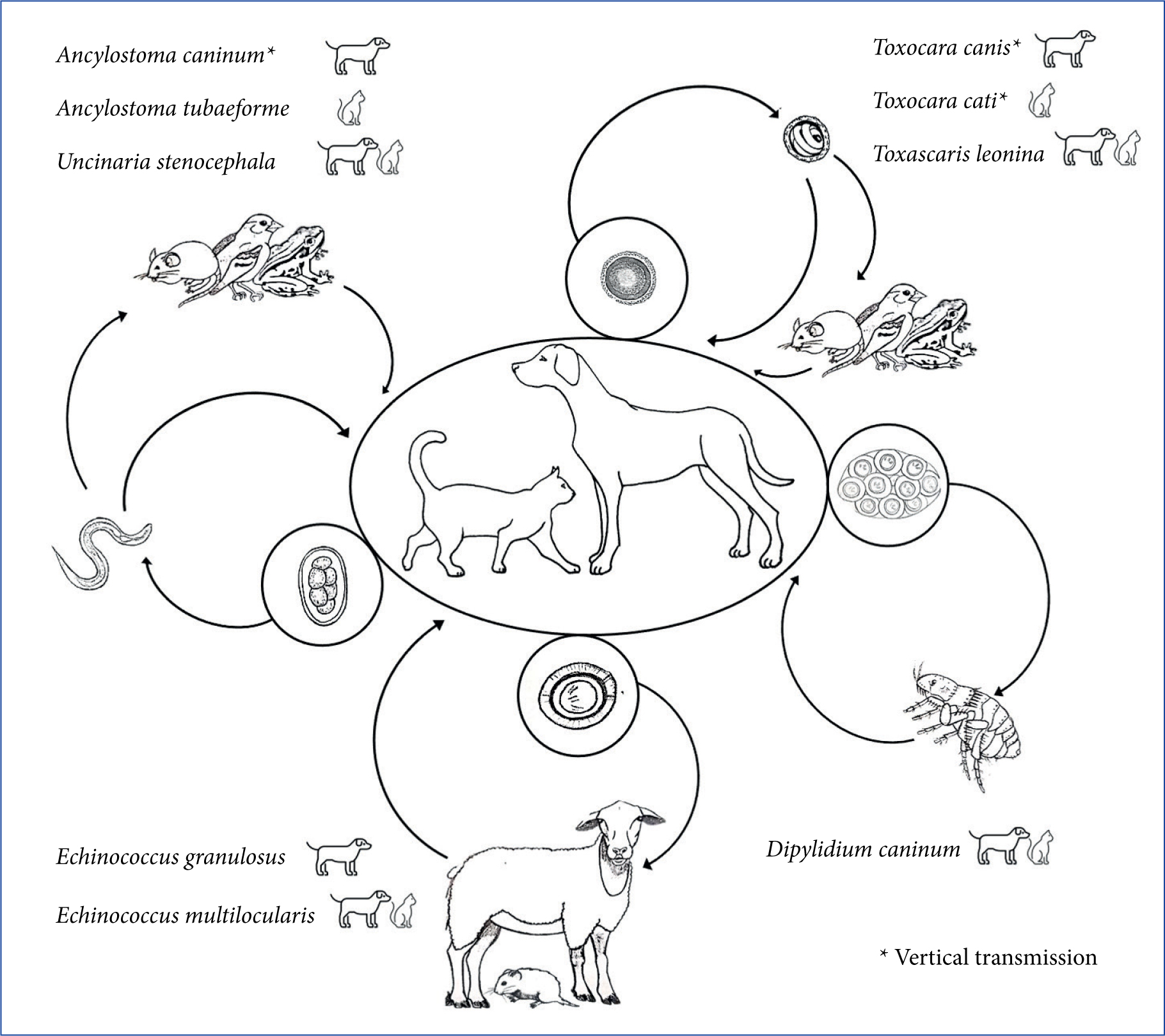

Trichuris vulpis, the ‘dog whipworm’, has a direct lifecycle and dogs acquire the infection through the ingestion of eggs contaminating the environment. This nematode, which mainly infects adult dogs and lives embedded in the mucosa of the cecum and colon (Figure 3), causes mucous diarrhoea, increased frequency of defecation, haematochezia, tenesmus, vomiting, anaemia, colic atony with constipation and, sometimes, inversion of the sodium-potassium ratio (pseudo Addison disease) (Traversa, 2011; Venco et al, 2011).

Dipylidium caninum is the most common tapeworm of dogs and cats, which become infected by ingesting fleas (intermediate host) containing the cysticercoid. The infection is often subclinical, but diarrhoea, constipation, loss of appetite, vomiting, licking and scratching of the perianal area can be observed in infected animals. The infection in people is a rare condition, sometimes reported in children (Portokalidou et al, 2019).

Especially in rural or suburban settings, cestodes of the genera Taenia, Echinococcus and Mesocestoides can infect dogs and cats through a ‘prey-predator’ cycle, in which different animals, depending on the species of the cestode, act as intermediate hosts (Romig et al, 2017). These parasites are particularly present in hunting and shepherd dogs as, in rural areas, they may prey on different animals and/or are frequently fed with organs of slaughtered animals (Morandi et al, 2020). Among them, Echinococcus granulosus is the aetiological agent of cystic echinococcosis, a potentially lethal disease acquired by the accidental ingestion of eggs from the environment (Otero-Abad and Torgerson, 2013; Wen et al, 2019). Mesocestoides spp. infection in companion animals may cause severe disease when dogs and cats accidentally act as second intermediate hosts: the tetratyridia (larval form) localised in the peritoneum may in fact be responsible for peritonitis, ascites, vomiting, diarrhoea, and anorexia with possible fatal outcome (Venco et al, 2005).

Cardiorespiratory nematodes

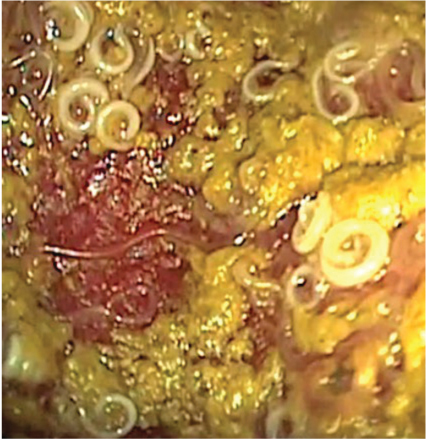

Several nematodes can infect the cardiorespiratory system of dogs and cats (Figure 4). Angiostrongylus vasorum lives in the pulmonary arteries and in the right ventricle of dogs, which acquires the infection through the ingestion of intermediate (terrestrial gastropods) or paratenic (e.g. frogs and chickens) hosts. The infection occurs more frequently in young dogs with exploratory behaviour, pica or with tendency to ingest grass (Helm et al, 2010). Angiostrongylosis causes highly variable clinical pictures in terms of severity and clinical signs, as infected dogs may show cardiorespiratory signs (e.g. exercise intolerance, cough), coagulation disorders, neurological signs or non-specific and gastrointestinal signs. Life-threatening conditions (haemothorax, pneumothorax, haemoabdomen, pulmonary or brain haemorrhages) can appear suddenly, also leading to death in subclinically infected dogs (Morgan et al, 2010).

Crenosoma vulpis lives in the trachea and bronchi and bronchioles of dogs and it has a life cycle like that of A. vasorum. The cuticle of the adult exerts an abrasive-mechanical action on the respiratory mucosa, leading to inflammation, coughing, sneezing, and even obstructive phenomena of the bronchial lumen as a result of the production of catarrhalpurulent exudate (Unterer et al, 2002; Conboy, 2009).

Dirofilaria immitis, which primarily affects dogs and less frequently cats, is transmitted by infected mosquitoes. Adult parasites live in the pulmonary arteries, causing progressive pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure. Acute episodes such as pulmonary thrombo-embolism and caval syndrome, caused by the retrograde displacement of adults from the pulmonary arteries to the right heart chambers, are potentially fatal (McCall et al, 2008). Cats can remain subclinically infected or present non-specific signs and, in some cases, sudden death may be the only detectable clinical sign (Venco et al, 2015).

Capillaria aerophila and Capillaria boehmi are respiratory nematodes which infect dogs living in sympatry with foxes (i.e. wild reservoirs). Cats can be infected only by C. aerophila. The definitive hosts acquire the infection by ingesting eggs from the environment, or earthworms that can act as facultative intermediate hosts. C. aerophila lives embedded in the mucosa of the trachea and bronchi and causes cough, dyspnoea and sneezing, while C. boehmi lives beneath the epithelium of nasal cavities and sinuses (Figure 5), causing nasal discharge from serous to mucus-purulent, sneezing, reverse sneezing, hypo- or anosmia, epistaxis (Traversa et al, 2009; Morelli et al, 2021a). Ectopic localisation or migration of C. boehmi with consequent meningoencephalitis and cerebral granulomas have been occasionally recognised as causes of neurological signs (Clark et al, 2013; Morelli et al, 2021b).

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus brevior — affecting bronchioles, alveolar ducts and alveoli, and bronchi and bronchioles respectively — are the most important respiratory parasites of cats. Their lifecycles are indirect and involve terrestrial gastropods as intermediate hosts. However, cats become more frequently infected by preying small rodents, reptiles and birds acting as paratenic hosts. Both parasites are responsible for variable clinical pictures characterised by upper and lower respiratory signs. The main differences are that T. brevior is more often fatal, especially in kittens, and it is transmitted vertically from the queen to the offspring (Morelli et al, 2021a).

Among these non-intestinal nematodes of dogs and cats, only D. immitis and C. aerophila infect humans on rare occasions (Lalošević et al, 2008; Simón et al, 2012).

Most infections caused by intestinal helminths and cardiorespiratory nematodes can be diagnosed through faecal examinations (e.g. floatation and Baermann techniques). Correct sampling, storage and identification of samples are essential to obtain reliable results. Faeces should be taken directly from the rectal ampoule. If taken from the ground, the part in contact with the soil should be avoided to limit the risk of sample contamination with pseudo-parasites (e.g. pollen, free living nematodes). Importantly, faeces should be removed from the soil or cage and appropriately disposed of to avoid environmental pollution. Moreover, the use of gloves and the careful washing of hands are recommended. Samples taken should be placed in clean and appropriately identified glass or plastic boxes and analysed within the shortest time possible. Alternatively, samples can be stored at refrigeration temperature (4/8°C) and analysed within 48 hours.

Ticks, fleas and transmitted diseases

Ticks and fleas are the most common ectoparasites of dogs and cats (Figure 6). They cause damage to the host via different modalities, i.e. blood deprivation, skin lesions, neurological diseases (tick paralysis) or allergic diseases (flea allergic dermatitis). Ticks most often infesting companion animals in Europe, i.e. Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Ixodes ricinus, Dermacentor spp., can transmit several pathogens such as Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia conorii, Borrelia spp., Babesia spp., and Hepatozoon spp. (Diakou et al, 2019; Morelli et al, 2019; European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2021). Ctenocephalides felis and Ctenocephalides canis are the most common fleas of dogs and cats. Pulicosis implies the high contamination of the environment where the pet lives, as adult fleas feeding on the host represent only 5% of the whole insect population, while the remaining 95% (eggs, larvae, pupae) contaminate the environment (Traversa, 2013). Fleas can transmit pathogens: the cestode D. caninum, acquired by the definitive host following the accidental ingestion of the arthropod containing the cysticercoid, some species of Mycoplasma and Bartonella, responsible for diseases in companion animals and, sometimes, some species of the Rickettsia genus. Diseases transmitted by fleas and ticks also represent an important threat for human health. Among the above mentioned pathogens, Bartonella spp. (for which cats are often asymptomatic carriers), R. conorii (cause of Mediterranean Spotted Fever) and Borrelia spp. (Lyme disease), cause important diseases in humans (Oteo and Portillo, 2012; Traversa, 2013; Colombo et al, 2021).

Regular checks of dogs and cats for ectoparasites is important and relatively easy. Diagnosis of pulicosis can be achieved by the direct visualisation of fleas, especially in body areas with less hair (e.g. abdomen, groin). Alternatively, flea faeces (visible as black-brown debris in the animal fur), can be collected brushing the animal with a fine-tooth comb. Then, debris should be put on a wet damp cotton wool or paper towel and, if reddish aureoles appear, flea infestation is confirmed. The reddish areas represent undigested blood contained in flea faeces (Cadiergues et al, 2014).

In cases of tick infestation, the correct removal of the parasite is pivotal to prevent tick-borne diseases. The empiric use of substances to remove the tick is highly discouraged (e.g. oil or gasoline), as this could induce the parasite to intensify blood suction and regurgitation and increases the risk of pathogen transmission. Tick should be removed with fine-tipped tweezers as close to the skin surface as possible (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021) or using specific tick removal tweezers available on the market.

Treatment and control: broad-spectrum formulations

Dogs and cats may harbour more than one of the abovementioned parasites at the same time (Heukelbach et al, 2012; Giannelli et al, 2017; Traversa et al, 2017; Diakou et al, 2019). Animals with outdoor access are at higher risk of infection with endo and ectoparasites (Beugnet et al, 2014; McNamara et al, 2018; Chalkowski et al, 2019). Nevertheless, indoor pets can also be threatened by numerous pathogens (Beugnet et al, 2014; Montoya-Alonso et al, 2014). There is a common misconception that cats living indoor are not prone to being parasitised, while there are several modalities through which parasites can affect indoor housed animals. Dogs and cats may:

- Be fed with raw or undercooked meat containing infectious parasite stages

- Ingest parasite elements brought home by the owners, for instance with dirty shoes

- Prey small animals which can enter the house

- Be bitten by mosquitoes infected by heartworms (Atkins et al, 2000; Traversa, 2012).

Moreover, cohabitation between cats and dogs is another risk factor, as both animals may go outside (i.e. dogs are walked, and cats are allowed to free-roam) and some parasites, including ticks and fleas, are shared between dogs and cats (Conboy, 2009).

There is no single treatment or prevention schedule that is suitable for every dog and cat. The selection and administration of medications should be set according to the individual characteristics of each animal and based on an aetiological diagnosis (in the case of therapy), and/or on the parasite/s to be prevented (in the case of prophylaxis), according to the epidemiological scenario in each area. The individual factors to be considered for appropriate planning of control programmes are age, physiological state, environment, lifestyle, diet and movements, as also reported by the guidelines of the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) (https://www.esccap.org/). Moreover, control programmes for internal and external parasites must be planned on a case-by-case basis, also taking into account possible zoonotic risks and owner compliance. For example, the formulations that contain a macrocyclic lactone allow for the control of intestinal nematodes and, in many cases, the monthly prevention of filariosis, angiostrongylosis and/or aelurostrongylosis. Isoxazolines, present in monoproducts or in formulations with a macrocyclic lactone, are effective against fleas and ticks (and sometimes other arthropods). Antifeeding products can also be used to prevent tick and flea infestations. Moreover, if a broad-spectrum product contains praziquantel or imidacloprid, it guarantees the control of tapeworms and fleas respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of antiparasitic classes labelled for treatment and/or prevention of endo- and ectoparasites in dogs and cats

| Classes | Efficacy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endoparasites | Ectoparasites | ||||||

| Nematodes | Cestodes | ||||||

| Cardiorespiratory nematodes | Intestinal nematodes | T | F | M | L | ||

| Pyrazino-isoquinolines | - | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| Phenylpyrazoles | - | - | - | + | + | - | + |

| Insect growth regulators | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| Neonicotinoids | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| Isoxazolines | - | - | - | + | + | + | - |

| Pyrethroids | - | - | - | + | + | + | + |

| Macrocyclic lactones | + | + | - | - | + | + | + |

| Octadepsipeptides | +/- | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Tetrahydropyrimidines | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Benzimidazoles and Probenzimidazoles | +/- | + | +/- | - | - | - | - |

| Imidazothiazoles | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

T: ticks; F: fleas; M: mites; L: lice; +: labelled; +/-: labelled for treatment and/or prevention of some species; -: not effective/not labelled

Conclusions

A plethora of broad-spectrum formulations is available on the market (Table 1), allowing the veterinary practitioner to choose the most suitable product for the animal and its owner, in terms of spectrum of activity, method of administration, compliance, speed of action and persistence. The use of broadspectrum products is advantageous not only for companion animals, that can be protected from both endo- and ectoparasites, but also convenient for the owner and veterinary practitioners. These factors can thus result in increased owner compliance and improved control of parasitic diseases.

KEY POINTS

- Roundworms and hookworms are the most widespread intestinal nematodes. They can cause life-threatening conditions especially in puppies and kittens and have also zoonotic potential.

- Dipylidium caninum is the most common tapeworm of dogs and cats, in which infections are usually subclinical. Echinococcus spp. is less distributed and, while it has low pathogenic potential in animals, it causes potentially fatal disease in humans.

- Dogs and cat can harbor several cardiorespiratory nematodes. Among them, Angiostrongylus vasorum and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus brevior in cats and Capillaria aerophila in both, are the most relevant. Dirofilaria immitis and C. aerophila can infect humans.

- Fleas and ticks can transmit several pathogens to pets and humans, some of which can be life-threatening. Also, they cause direct damage to their hosts, i.e. blood deprivation, skin lesions, neurological diseases (tick paralysis) or allergic diseases (flea allergic dermatitis).

- Broad spectrum parasticides allow the control of both endo- and ectoparasites simultaneously, reducing the risk of infection for animals and, indirectly, for humans.