Fleas are considered the most prevalent ectoparasite, with sources stating that 1:5 cats and 1:10 dogs have fleas at any given time (Elsheikha, 2017). According to The People's Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report, 82% of dogs and cats and 13% of rabbits in the UK were treated for fleas in 2017 (PDSA, 2017). Despite this, many owners are not aware of how pets can become infested with fleas.

Broadly speaking, there are two main situations in which a client will approach veterinary staff for advice on fleas:

Many clients may understand the need for preventative flea treatment, but not the necessity for regular prophylaxis in conjunction with environmental control methods. Those with an established infestation may have previously sought advice or treatment elsewhere which has been unsuccessful.

The role of the veterinary nurse (VN) is to educate clients on the life cycle of the flea and its associated control measures, its links with the tapeworm Dipylidium caninum (D. caninum) and how to treat an established infestation, while also managing the client's expectations.

Flea life cycle

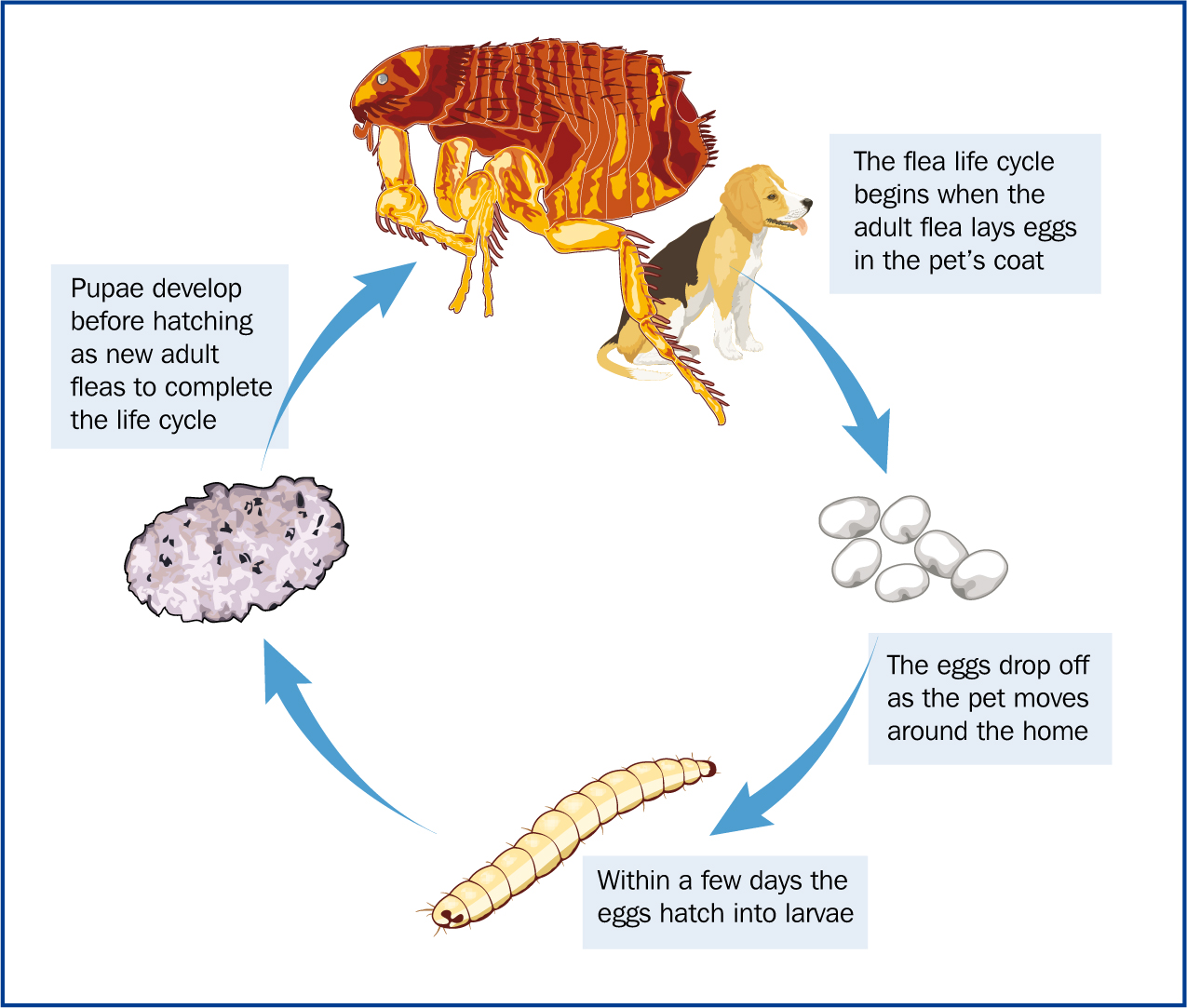

Adult fleas lay eggs within 24 hours and can lay 40–50 eggs per day. The eggs hatch in 1–6 days and the larvae can then pupate in as little as 10–20 days under warm, humid conditions. Adult fleas can then emerge from the pupae in 3 weeks. Under most household conditions, the life cycle can be completed in less than 8 weeks. The speed and multiplication of this life cycle means that an infestation with even just a few fleas can lead to heavy environmental contamination of homes very quickly. At any one time, 95% of the flea problem exists in the home as eggs, larvae and pupae (Figure 1).

Although adults can emerge from the pupae within a few weeks, if conditions are unfavourable, pupae can remain viable for 1–2 years. This means that infestation can be established even if mammalian hosts have been absent for some time. Pupae hatch in response to heat and movement and so are reactivated by the presence of possible hosts. These can be unfortunate people entering a home that has been vacant for months or even years.

Link between fleas and D. caninum

D. caninum tapeworms are typically up to 50 cm in length and live in the intestines of cats and dogs. Fleas and lice act as intermediate hosts. Infection occurs either by grooming off fleas or by ingestion of infested prey. Humans may also be infected by accidental ingestion of fleas in contaminated food items or under fingernails. The adult tapeworms are of low pathogenicity, but segments are highly motile and can cause revulsion and reduction of the human–animal bond when found moving around the anus of pets or in bedding and on furniture. Both zoonotic risk and prevention of infection comes from adequate flea control. Regular infections with D. caninum in household pets implies poor flea control and may act as a sentinel for more significant zoonotic flea-borne pathogens such as Bartonella spp.

Control measures

Treatment of the pet

Adult fleas can lay eggs within 24 hours so the adulticide chosen must kill fleas within that timeframe. They must also be administered frequently enough to continue to prevent flea egg-laying. The time after application of the adulticide at which fleas survive long enough to lay eggs is known as the ‘reproductive break point’. If the reproductive break point is reached, flea control will fail. Frequent swimming or shampooing may affect the efficacy and duration of action of imidacloprid and fipronil spot-on solutions, so this should be considered when choosing a product. Many flea products are also effective against other parasites so other parasite control requirements will influence product choice.

Environmental control

Environmental treatment to reduce eggs, larvae and pupae will decrease the time required to bring an infestation under control. Spray cans containing a larvicide/ovicide and an insect growth inhibitor used in household environments are useful to reduce flea and larval numbers, while also preventing development into pupae. When treating the environment directly, all areas the pets frequent, such as cars, furniture and bedding, must be treated. Effective penetration of chemicals from aerosol-based products can be poor unless used from the correct distance and after removal of obstructing objects such as children's car seats, pillows, and cushions. These should be treated separately. Care must be taken to ensure that instructions are followed carefully and that fish, birds, invertebrate pets and cats are removed while treatment is taking place. There is no defined ‘safe time’ for the return of these animals into the environment post treatment. However, once the product has settled onto surfaces and is no longer present in the air, pets can be returned. This would typically be in approximately 2 hours time if the product was used appropriately and the room well ventilated. VNs and veterinary surgeons (VS) are advised to consult the manufacturer guidelines for the chosen product.

Systemically acting products containing lufenuron can be used in pets to prevent flea eggs from hatching. Some adulticides such as imidacloprid and selamectin are shed into the environment after the pets have been treated, reducing environmental egg and larval contamination. Many spot-on flea products also contain the growth regulator Smethoprene to achieve a similar effect. Daily vacuuming of areas frequented by flea-infested pets has also been demonstrated to reduce pupae numbers in the environment (Hink, 2007), as has hot-washing of pet bedding to at least 60°C. Although an adulticide alone used on all pets frequently enough will break the flea life cycle, without treatment of the environment, some flea infestations will take many months to eliminate.

Role of the nurse

The VN has an integral role in delivering flea control advice. Clients often feel more comfortable speaking to VNs and asking them questions as they are commonly perceived to be more approachable and to have more time to offer than VSs (Tottey, 2015).

A VN who has been trained by the Animal Medicines Training Regulatory Authority (AMTRA) as a suitably qualified person (SQP) can be useful as they can prescribe and dispense certain anthelmintics under the remit of their qualification. The benefit of this is that they do not need to consult with a VS prior to supplying a client with a product (Ackerman, 2012). The provision of advice is not limited to SQPs — all VNs can offer advice to clients. The ideal VN is one who is both enthusiastic and passionate about flea control and educating clients (Tottey, 2015). If multiple staff members are offering advice, protocols should be standardised to ensure advice is accurate and consistent. Training and support should be given to less experienced VNs or student VNs to ensure advice is correct and the delivery is polished. Clients need to feel confident that the VN knows what they are talking about; otherwise, they may not comply with the advice (Wild, 2017).

As previously mentioned, the two main incidences in which a client will seek flea control advice are when they have an established infestation or when they need preventative treatments. VNs can give this advice in a variety of settings such as in dedicated nurse clinics or over the phone. However, we must also aim to give advice when the client is not seeking it in order to prompt and remind them about the need for regular treatment, e.g. at a postoperative check or when booking in for a vaccination appointment. Often clients have good intentions regarding flea control but simply forget about the need for repeated treatments. Reminding the client when he or she is in the practice or by using a text/email reminder system can prove to be an effective way to increase compliance.

A 2012 study by Onepoll of 2000 British cat and dog owners found that 25% of clients would welcome discussions on parasite control (Gerrard, 2016). A client information evening could provide an opportunity to educate multiple clients at the same time on topics such as flea control; one-on-one sessions could then follow in which individually tailored plans could be formulated.

Preparation is key

When offering advice to clients, it is useful, where possible, to have a clean and tidy consulting room. By taking the client into a quiet room that is free from external noise and distraction, communication is often improved as the obstacles to communication have been minimised.

Many areas in a veterinary practice are clinical but a consulting room dedicated to nurse clinics should be decorated with appropriate posters and models, as these can be used to aid discussions. It is also useful to have a flea comb available to perform coat brushings, weighing scales (if the room size allows) and a computer so the VN can easily access the client/patient's clinical history.

How should we communicate with clients?

First impressions are very important; this is often what a client remembers and a positive interaction has been shown to cement the client's bond with the practice, thus increasing client compliance. If the client has phoned for advice, the front-of-house staff should have a friendly tone of voice and the reason for the call should be quickly identified so that it can be transferred to the most appropriate person for advice (if required).

For clients attending an appointment (pre-booked or walk-in), again, the front-of-house staff are usually first to greet them. Where possible, it is useful to have an awareness of which clients are coming in for an appointment and with which animal; this enables the ‘booking in’ process to be more personal.

Prior to calling the client into the consulting room, the VN should familiarise themselves with the patient's clinical history. The VN should also ensure he or she has a clean, tidy, professional appearance and a name badge should be worn so that the client can easily identify who they are communicating with (Ackerman, 2012). When calling the client into the consulting room, Faulkner (2017) notes that using the patient's name rather than the client's surname, as well as making a fuss of the pet, demonstrates that the VN cares about the patient, and the personal approach contributes to a positive relationship with the client. A friendly facial expression and tone of voice, as well as open body language, should be maintained throughout.

There are seven documented Cs of communication as discussed by Hedberg (2016). When considered, they can enable clearer communication. The seven Cs are:

The VN should begin the consultation by obtaining a detailed history from the client. Many clients will offer information and it is essential that the nurse listens carefully. Clients who feel their opinion is valued are more likely to take the advice offered. In conjunction with this, the nurse must also ask prudent questions (both open and closed) to direct the client to disclose information necessary to formulating a control plan.

Active listening is a useful technique, which involves asking the client a question and then repeating their answer back to them. This useful method can enable the VN and client to ensure that each has understood the other, which builds rapport and increases compliance (Ackerman, 2012; Loftus, 2012).

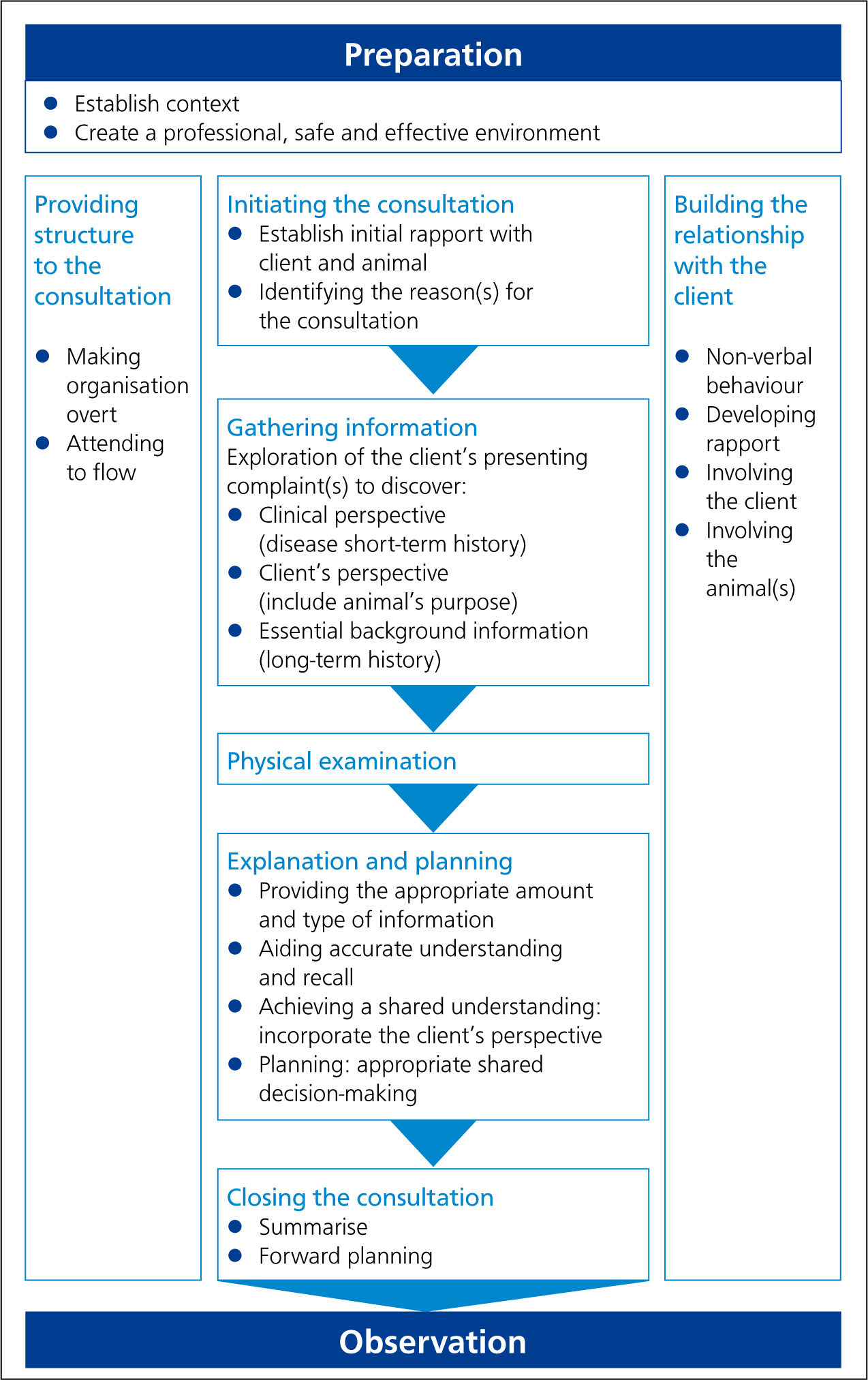

The Cambridge-Calgary consultation model (Figure 2) provides a framework or structure on how to gather information, explore it and then summarise this to the client. Reference to this model can be useful for VNs who are unsure about how to structure a consultation. Wiggins (2016) believes that use of this model can facilitate easier and clearer communication.

Flea control consultations need not only be based on conversation; they can also be interactive. Provision of information in a variety of formats is beneficial as this caters for all learning styles. Different methods of providing information include:

How can we ensure our clients are treating their pets correctly?

Many issues with flea control relate to client understanding and subsequent compliance. Clients may not administer the treatment correctly, frequently enough or treat all the animals (and at the same time), and may not treat the environment fully (Elsheikha, 2017). Clients may also not have an awareness of the difference in efficacy of veterinary products compared with those provided by other retailers; the previously mentioned Onepoll study found that 38% of owners believed them to be equally effective (Gerrard, 2016). While high street retail products (AVM-GSL products) have their place, VNs must educate clients on the differences (Gerrard, 2016).

Risks posed by fleas

While we do not want to scare clients, it is vital that we provide them with all of the necessary information. This includes the risks associated with fleas so they can make informed decisions. It has been shown that clients who feel involved with the decision-making process are more likely to take the advice given and continue regular treatments. A greater understanding of the health implications for themselves and their pet can also increase compliance.

A summary of the risks fleas pose is as follows:

Fleas can affect a variety of species

The most common flea is Ctenocephalides felis—the ‘cat flea’: this can infest a variety of species including cats, dogs, rabbits and hedgehogs. While this is the most common, there is also the dog flea; Ctenocephalides canis, which can be found on dogs and occasionally cats. Then there is the human flea; Pulex irritans, which can infest humans and animals (Elsheikha, 2018).

Unprotected pets in the house

A common misconception is that pets kept exclusively indoors cannot be affected by fleas. It is vital for VNs to educate clients that fleas can enter the home on other animals or clothing/material. Unprotected pets can pick up fleas when out and about, be that in the garden or out on a walk from where wild, stray or other untreated animals have been (Elsheikha, 2017).

Fleas can survive on a variety of species so it is imperative that all animals in the household are treated frequently enough (according to manufacturer guidelines) and at the same time. In the absence of this, fleas can continue to breed despite the client administering treatment.

Life cycle of the flea and environmental stages

Adult fleas comprise only 5% of the total flea population; the other stages are present within the environment. Therefore, without sufficient environmental control, re-infestation can continue even if the animals have been treated. An integrated approach is required; treat all pets with a suitable long-acting adulticide (refer to manufacturer's guidelines on frequency of dosage) and implement environmental control measures as follows:

Coat brushings: does the pet currently have fleas?

A full clinical examination should be performed; if any abnormalities are detected, the patient should be referred to the VS. Coat brushings are a useful technique to use in a flea advice consultation. This can help determine if the pet has a flea problem at this time and can help when explaining the life cycle of the flea. The coat should be brushed onto damp white paper or cotton wool using a flea comb. If the dirt shows blood red, this indicates flea dirt and presence of fleas. It is vital for VNs to explain that it is rare to see the fleas themselves (they are small and fast-moving) and that this basic test provides a good alternative assessment.

Choosing the correct product

Product choice is key to good compliance. By involving the client in the decision-making process, the VN can tailor the control plan to the client's preferences and the animal's lifestyle. It is important to consider the following when choosing a product (although this list is not exhaustive):

Conclusion

VNs have an integral role to play in the implementation of flea control plans. Through education of clients on the life cycle of the flea, including its environmental stages, the risks they pose to both pets and humans and their control measures client compliance can be increased. VNs must work in partnership with their clients to reach mutual, informed decisions which will improve the health and welfare of the pet and cement the client–practice bond.