Veterinary nurses who provide nutritional advice to clients with pruritic dogs are faced with an ever-increasing array of low-allergy diets. Selection of a diet can be difficult because each animal's requirements are unique. However, as most itchy dogs should be food-trialled at some stage in the work-up of their skin disease, it is important to be able to guide clients about the best diet for their pet. Recent studies have demonstrated that the selection of an appropriate diet and client education around the diagnosis and treatment of their pet's condition aids compliance (Tiffany et al, 2019), and hence increases the chances of establishing a diagnosis.

Clinical signs of cutaneous adverse food reaction

A diagnosis of cutaneous adverse food reaction (CAFR) should be included on every list of pruritic skin diseases in the dog. While CAFR can affect any age or breed of dog, the literature does suggest some predispositions. Although CAFR has been recorded in dogs as old as 13 years, it is generally seen in much younger animals. About 22–38% of dogs start with clinical signs between 6 and 12 months of age (Olivry and Mueller, 2019), suggesting that dogs with CAFR tend to present at a slightly younger age than those with canine atopic dermatitis—although there is overlap between the two diseases. The Labrador, golden retriever, West Highland white terrier and German shepherd dogs account for about 40% of those affected (Olivry and Mueller, 2019).

CAFR is known to present with a wide range of cutaneous and non-cutaneous signs. Most dogs with CAFR are pruritic. The pruritus tends to be generalised, although pruritus is often directed at the ears, feet (Figure 1) and abdomen. Other manifestations of CAFR include bacterial skin infections, otitis externa which may be bilateral or unilateral, lick granuloma and ‘interdigital cysts’. The signs of CAFR also overlap with those of canine atopic dermatitis making the two diseases indistinguishable on the basis of clinical signs alone.

Non-cutaneous manifestations of CAFR are less well described but have been shown to include gastrointestinal signs (colitis, diarrhoea, increased faecal frequency), symmetrical lupoid onychodystrophy (Figure 2), conjunctivitis, sneezing and behavioural changes (Mueller and Olivry, 2018).

Making a diagnosis of CAFR

Unfortunately, there can be no shortcuts to the diagnosis of CAFR or food ‘allergy’ in dogs. Reactions to food remain a complex process. Allergy plays a part in some cases, and in these animals, it may be that circulating levels of antibody give an indication to the inciting cause. In food-allergic individuals, small amounts of the offending food can provoke a severe reaction and those signs can be dermatological or gastrointestinal. When food intolerance is involved, animals produce reactions to the food in a non-antibody-mediated fashion. In such cases, animals may be reacting to a component of the food that is producing a specific pharmacological reaction. In the author's experience, these reactions are often graded, where small amounts of the food trigger a mild response and increasing amounts produce a proportionately increased reaction. With such a range of mechanisms, the use of either intradermal allergy testing or in vitro blood sampling to diagnose food ‘allergy’ is, in the author's opinion, inappropriate and can never replace a properly constructed food trial.

Several new studies published in the last 12 months have confirmed again that both serum and saliva assays for CAFR are of little benefit. One study showed positive results in apparently healthy dogs (Lam et al, 2019), and a second study showed no difference in positive reaction between allergic and healthy dogs (Udraite et al, 2019). Both studies concluded that a well-formulated elimination diet remains the gold standard for a diagnosis of CAFR.

Every veterinary dermatologist has their favourite home-cooked combination for a food trial whether it be pork and lentil, fish and potato, lamb and rice, or boiled beef and carrots. There can be no right or wrong diet for any animal, providing the protein and carbohydrate is unique to that individual and the potential cross-reactivity of different protein sources is also considered. Foods that have been commonly implicated as causes of CAFR in the dog include beef, dairy products, chicken and wheat (Mueller et al, 2016). These are therefore probably best avoided unless you can be assured they truly represent novel foods for a particular dog.

A clinical history is paramount in deciding which foods to choose. When asked, owners are usually more than willing to provide information about dietary intolerance and preferences they have recognised in their pet. For example, it is always useful to find out if a client's dog will eat lamb before suggesting it as a suitable diet. Veterinary nurses play an invaluable role in being able to spend time with clients and get a full dietary history in order to be able to recommend an appropriate diet. Dog owners do not always appreciate that anything their pet is consuming needs to be considered as a potential allergen, including treats used to administer medication, so it is important that all dietary sources are identified.

Clients' personal preferences are important when selecting a diet. Quite understandably, vegetarians will often not cook meat for their pets. Busy working professional people will often not have the time to prepare a home-cooked diet. Owners of giant breeds will rarely be able maintain a home-cooked diet regardless of how conscientious their initial intentions. Table 1 gives a rough guide as to the amount of home-cooked food a dog will need. For an 80 kg St Bernard, this would therefore equate to about 1.6 kg of protein and 3.2 kg of carbohydrate daily. There is no doubt that some owners will find the time, however busy their schedule, to prepare food for their dog. However, for many, it has got to be convenient in order to work. Only the most dedicated of owners will cook 7 lb of rice every day for their Newfoundland.

Table 1. Approximate weights of home-cooked food needed by weight of dog

| Dog weight | Cooked weight of protein | Cooked weight of carbohydrate |

|---|---|---|

| 10 kg | 200 g | 400 g |

| 20 kg | 400 g | 800 g |

| 40 kg | 800 g | 1600 g |

| 80 kg | 1600 g | 3200 g |

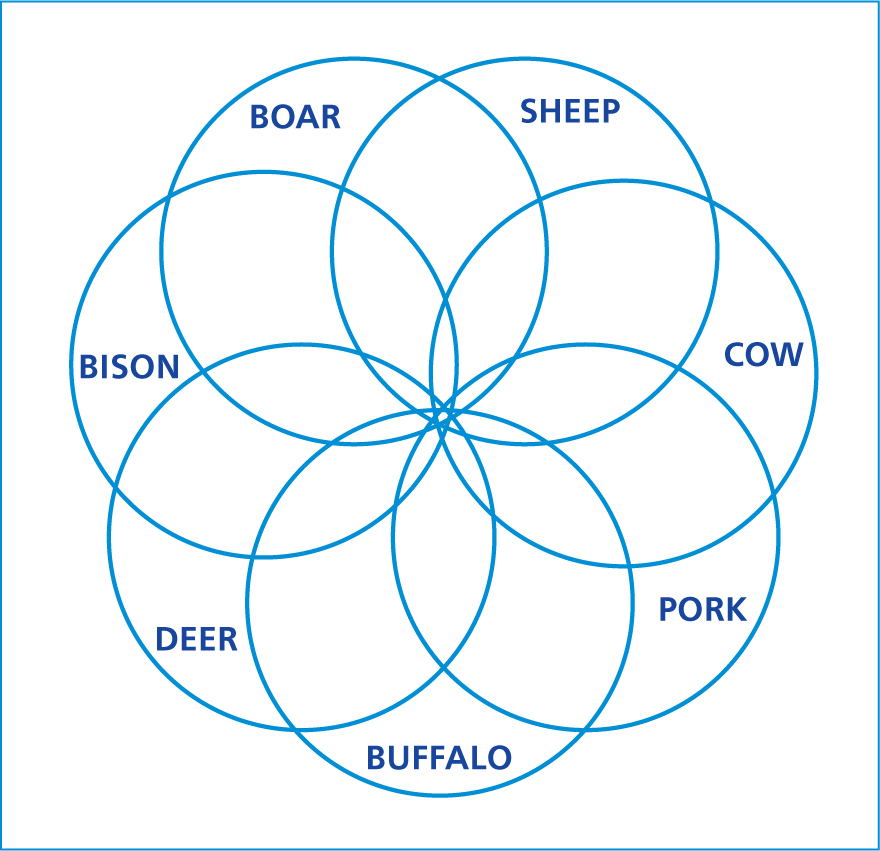

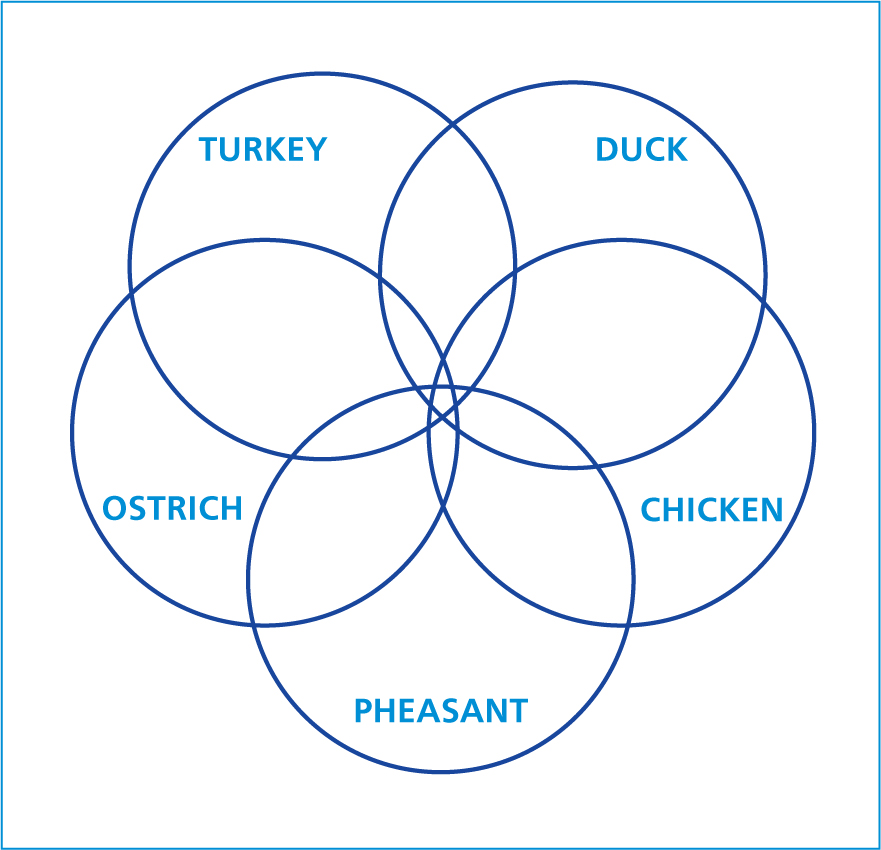

Cross-reactivity between different protein sources is well recognised in humans. Individuals with allergy to cow's milk often also have allergy to milk from other ruminants such as goat or sheep. Cross-reactivity is also seen between the different ruminant meats and there are published reports suggesting cross-reactivity between different poultry protein and fish proteins. Similar cross-reactivity is beginning to be recognised in canine food reactions (Bexley et al, 2017; 2019). In practical terms, this means that a dog that is intolerant to beef may also show similar reactivity to protein from related species, e.g. bison, buffalo and venison. Figures 3 and 4 demonstrate the different types of protein that may cross-react. The implication of cross-reactivity of proteins is that even if a protein appears to be novel, if it is related to a common protein, it is likely that a dog may be allergic to both (e.g. a novel protein such as bison may cross-react with beef).

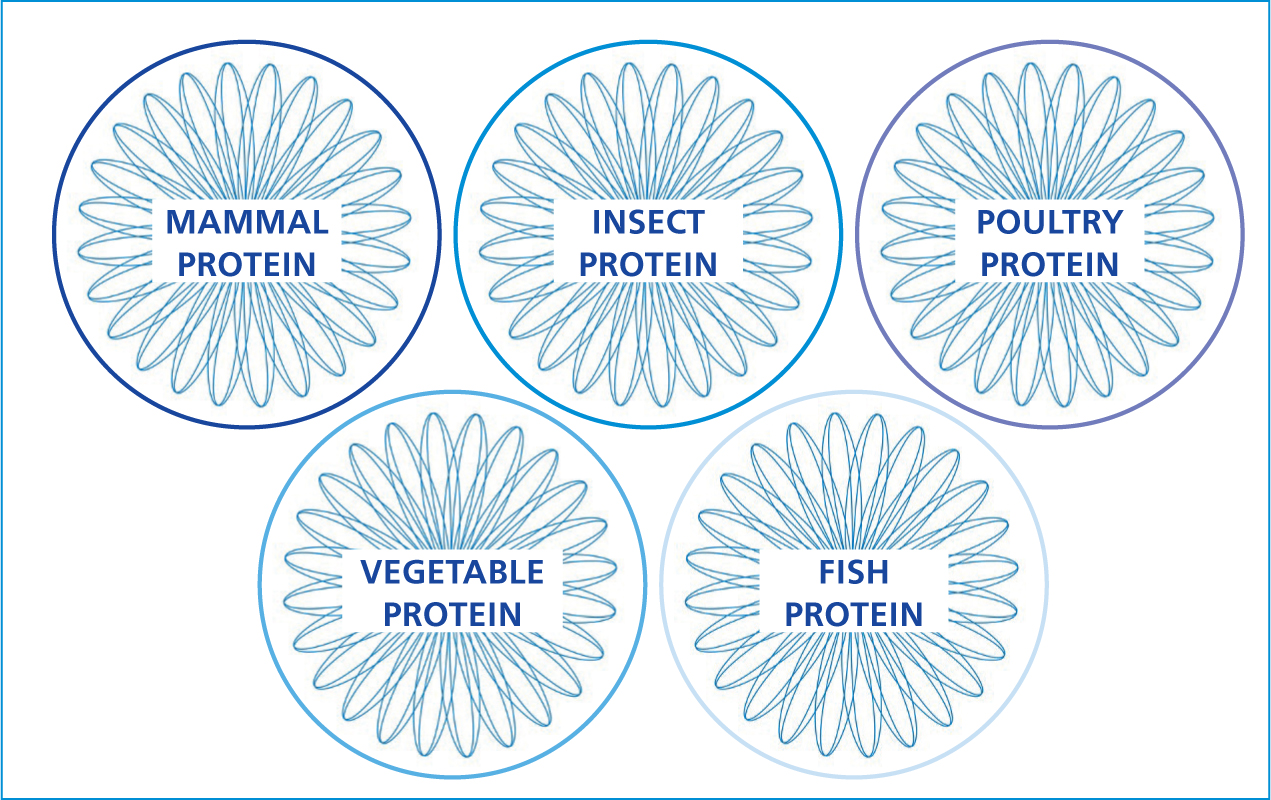

When choosing a novel protein, the author will tend to stay away from closely-related protein sources to minimise the risk of cross-reaction, and select a protein from a different group to those being consumed by the dog (Figure 5). As there is now a wide choice of different novel protein sources available in numerous commercial diets, e.g. vegetable-based diets and insect-based diets, the institution of a novel protein diet can be achieved. The selection of a novel carbohydrate should also be made on the basis of a carefully taken history to choose a food source that the dog has not consumed before; suitable carbohydrates may include rice, potato, sweet potato, pumpkin, squash or quinoa.

Contamination of commercial diets has also been reported in the literature. Numerous studies, using a variety of methodologies, have identified undisclosed foods within commercially prepared foods (Horvath-Ungerboeck et al, 2017; Kanakubo et al, 2017; Fossati et al, 2019). Sometimes these ingredients are hidden within a broad description on the label such as ‘animal derivatives’ in other cases, no declaration is made on the container that it contains anything other than the components specified on the main label. While it can be argued that many of the techniques used to identify foreign proteins are highly sensitive and not necessarily an indication of gross contamination, care should be taken in selecting commercial diets where the ingredients are not listed as individual items.

Hydrolysed diets seem to overcome many of the problems associated with cross-reactivity of proteins and contamination. Where the protein is highly hydrolysed and little of the native protein remains, they are unlikely to trigger cross-reactions. Studies assessing the contamination of commercial diets have shown the presence of undeclared proteins to be very rare (Olivry and Mueller, 2018). While a hydrolysed diet does help overcome some of the problems of diet selection, they are a relatively more expensive option than other commercial diets and the hydrolysis of proteins can lead to a reduction of palatability and mild gastrointestinal signs in some dogs. Several excellent hydrolysed diets are available which, in the author's opinion, provide an excellent and convenient way to undertake an elimination trial in a dog. Several studies have shown that even when dogs are allergic to a protein or carbohydrate, it does not invoke a reaction in most cases if the food has been hydrolysed (Bizikova and Olivry, 2016; Matricoti and Noli, 2018). It is therefore important when chatting to an owner than the ‘fussiness’ of the dog is checked. A hydrolysed diet may suit an active spaniel but not necessarily a West Highland White Terrier that may do better on a home-cooked diet. Table 2 summarises the different criteria that should be considered when selecting an elimination diet for a dog.

Table 2. Factors to consider when selecting a low-allergy diet

| Factor | Comment |

|---|---|

| Palatable | Palatability is essential; texture, smell and protein levels all contribute to this |

| Suitable formulation | The formulation should be appropriate for the breed; small kibble size for small dog |

| Convenience | Convenience contributes to long-term compliance. If an owner cannot sustain a diet because of lifestyle, inconvenience, etc, they are unlikely to continue with it |

| Cost | Cost becomes more critical the longer a dog is on a diet and the heavier it is. It is worthwhile to do some price comparisons; veterinary diets on a weight basis are often only slightly higher cost than pet shop products |

| Nutritionally complete | A home-cooked diet does not have to be completely balanced if used for a few weeks but must be if used over long periods or as a maintenance diet |

| Protein and carbohydrate source | The types of components will depend on the food history of the dog. What may be a novel protein, e.g. tofu, for one dog may not be for another. The potential for cross-reactivity of proteins is important |

| Hydrolysed diet | Hydrolysed diets where the whole protein has been broken down into smaller polypeptides through a process called hydrolysis to reduce their allergenicity avoids the need to select a novel protein; however, these diets have disadvantages in terms of reduced palatability and increased cost |

Owner compliance around feeding a diet is important. When prescribing a diet, it is important to ensure that owners are aware that the diet should be fed to the exclusion of all other food. Often, owners need to be told specifically that a corner of toast or licking out a yoghurt pot have to be stopped during the period of the food trial. The diet also needs to be fed for an extended period of time. There is currently no consensus on the duration of an elimination diet trial. One study suggests that a trial period of 5 weeks is sufficient to produce complete clinical remission in more than 80% of patients. Increasing the trial length to 8 weeks leads to complete remission in 90% of dogs (Olivry et al, 2016). These findings suggest that a diet trial should be a minimum of 8 weeks.

While a remission of clinical signs during the feeding of an elimination diet is a strong indicator of a CAFR, the diagnosis should really be confirmed by dietary challenge. Many dogs with canine atopic dermatitis show seasonal signs of pruritus, which means they may move into a natural period of remission while on a diet, giving a false impression. Challenge therefore helps to establish a definitive diagnosis and also allows for the formulation of a maintenance diet going forward. The veterinary nurse can guide owners here by helping to document reactions to different food as they are re-introduced, and select a diet that does not contain any components that are likely to trigger a reaction. New foods should generally be introduced every 5–7 days. A food log which can be brought to nurses' recheck appointment can be useful.

Conclusion

The veterinary nurse can play an important role in helping owners to select an appropriate elimination diet for their dog. There is no one diet that suits every dog so a careful history-taking and discussion with the owner is always needed to decide on the type of diet that is most suitable. The veterinary nurse can also encourage owners during the diet phase when compliance is essential and aid clients to undertake dietary challenge at the end of the trial to identify offending foods and select a maintenance diet.

KEY POINTS

- The veterinary nurse is an invaluable member of the veterinary surgeon-led team and should be used to advise clients on diets.

- An exclusion diet should form an integral part of the investigation of any pruritic dog.

- Selection of an appropriate exclusion diet should involve a careful history and discussion with the client.

- Home-cooked diets remain the gold-standard food trial for a dog but the risk of cross-reactivity of different proteins should be considered.

- Hydrolysed diets provide an excellent alternative to a home-cooked diet.