Veterinary nurses (VN) play a vital role in the education of clients on parasite control. Many clients feel more comfortable discussing parasite prevention with a VN as they are perceived to be more approachable and may have more time to offer the client (Tottey, 2015). There are a wealth of opportunities for discussing parasite control, be that in a dedicated parasite clinic, in reception, over the phone or following on from a veterinary consultation. No matter what the scenario, clients should always have access to the best information and a passionate, informed VN. By communicating efficiently with clients, compliance and satisfaction for the client and VN can be increased. Compliance benefits the client through obtainment of knowledge and understanding and therefore also benefits the pet as their health and welfare is improved. Excellent compliance is also beneficial to the practice as the client bond is strengthened and staff have increased satisfaction and motivation (Ackerman, 2012).

Cats and dogs are exposed to an ever increasing range of parasites. Some are considered to be ubiquitous and exposure is therefore hard to avoid — this is true for cat fleas and the roundworm (Toxocara spp.). Regular treatment for these parasites is essential as there is both disease and zoonotic potential. Prevention for other common parasites is based on risk, e.g. lifestyle and geographical location. Parasites to consider in the UK include: ticks, Ixodes spp. and Dermacentor reticulatus; tapeworms, Echinococcus granulosus, Taenia spp., Dipylidium caninum; and lungworm, Angiostrongylus vasorum. These parasites have the potential to cause significant disease to pets and present a zoonotic risk to clients and veterinary staff (Morgan et al, 2005; Overgaauw and Van Knapen, 2013; Craig 2014).

The role of the VN in parasite control and for the aforementioned parasites will be discussed within this article. For more information the reader is directed to the previous article ‘Parasite control clinics and the role of the veterinary nurse’ published in The Veterinary Nurse in April 2017 (Richmond et al, 2017).

Basic parasite control for veterinary nurses

Fleas

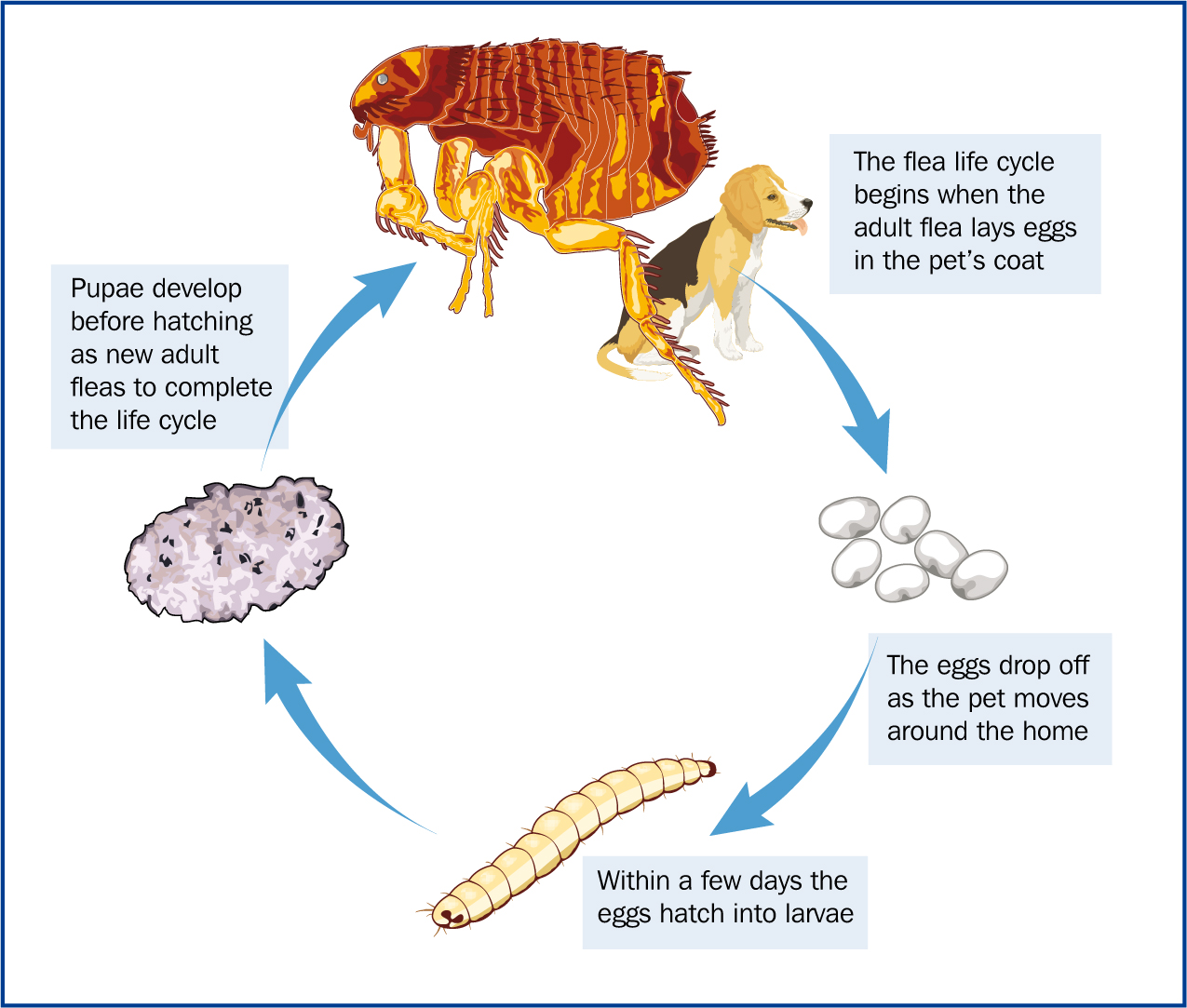

Due to climate changes and the use of central heating in homes the environmental stages of the cat flea can persist all year. This results in an increased flea challenge and the establishment of infestations if routine prophylaxis is not utilised (Coles and Dryden, 2014).

Preventative treatment for fleas

Roundworm

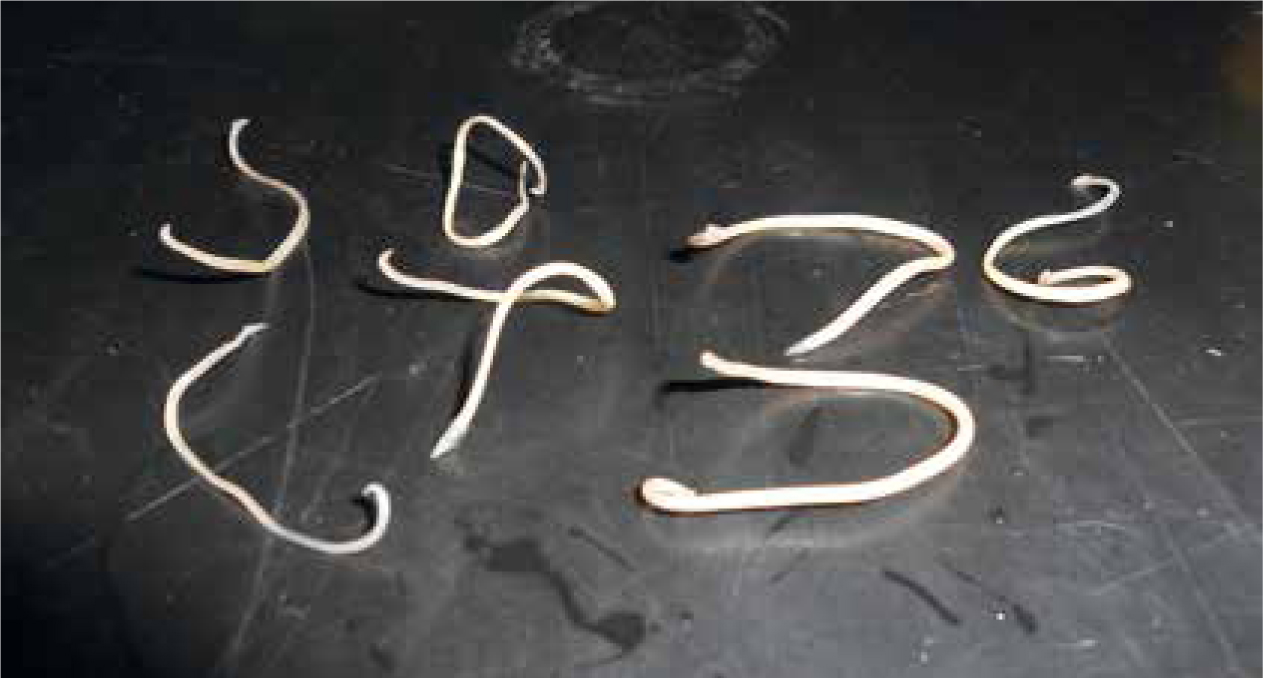

All puppies and kittens are infected by Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati (Figure 2) at or after birth via the transplacental (puppies) and transmammary (puppies and kittens) routes (Overgaauw and Van Knapen, 2013). In the UK (wider prevalence ranges have been demonstrated in European studies), if untreated, 5–10% of adult domestic dogs and 10–26% of adult domestic cats shed Toxocara eggs (Turner and Pegg, 1977; Wright and Wolfe, 2007; Overgaauw and Van Knapen, 2013; Wright et al, 2016). The eggs contaminate the environment where they develop to embryonated eggs which present a zoonotic risk to humans.

Preventative treatment for roundworm

Ticks

Due to the milder climate ticks are able to feed throughout most of the year leading to increased tick exposure to pets (Smith et al, 2011). 2.37% of ticks have been shown to carry Borrelia spp. which causes Lyme disease (Abdullah et al, 2016). Recent research has demonstrated an established endemic focus of Babesia canis in Essex (Phipps et al, 2016).

Does the pet need preventative tick treatment?

There are several factors to consider:

Preventative treatment for ticks

Tapeworm

E. granulosus is zoonotic and results in the development of large fluid filled hydatid cysts. Dogs are infected through consumption of these cysts and humans via ingestion of infective eggs passed in dog faeces. Cats and dogs with flea infestations are at risk of D. caninum and those which hunt/scavenge or are fed a raw, unprocessed diet are at risk of Taenia spp. (Wright, 2013; Richmond et al, 2017).

Does the pet need tapeworm treatment?

Preventative treatment for tapeworm

Lungworm (A. vasorum)

A. vasorum (Figure 3) is transmitted through the ingestion of slugs, snails and/or grass which may contain them. A. vasorum is endemic within the UK, however the distribution is non-uniform (Richmond et al, 2017).

Does the pet need lungworm prophylaxis?

Preventative treatment for lungworm

A dedicated parasite nurse?

The ideal VN to communicate with clients is one who is enthusiastic and passionate about parasite control, the education of clients and improving the care of pets (Tottey, 2015). Whether to have one dedicated parasite nurse or several will depend on the practice involved. If multiple VNs are chosen it is vital that advice and protocols are standardised. It is imperative the VN/VNs involved keep their knowledge up to date, parasites are both diverse and complex and this should be appreciated (Elsheikha, 2017b). Less experienced VNs or students should not be excluded from being involved, as this is vital for training and improving self confidence. They should, however, receive adequate training and support, to ensure delivery is polished, advice is correct and the VN does not feel nervous/stressed (Wild, 2017).

Consideration should be given to whether it is useful to have the VN/VNs undertake the suitably qualified person (SQP) qualification offered by the Animal Medicine Training Regulatory Authority (AMTRA) (Figure 4). This would enable the VN to prescribe and dispense POM-VPS and NFA-VPS anthelmintics. Utilising an SQP negates the need for consultation with a veterinary surgeon prior to prescribing/dispensing a product (Ackerman, 2012).

Since the introduction of the Royal Charter in February 2015, registered VNs are accountable for their actions and there are legal, ethical and professional consequences of decisions made. VNs should also ensure they are working within the principles of the Code of Professional Conduct (Wild, 2017).

Communication

The first impression

First impressions are vital; this is often what the client remembers, therefore ensuring this interaction is positive is paramount to client bonding and compliance. Greeting clients by name and paying their pet attention (Figure 5) is appreciated and helps to cement the bond between the practice and client. This requires a whole team approach, a client's first interaction with the practice is normally with the front of house staff over the phone or face to face, therefore all staff need to be aware of the importance of this. It may not always be possible, but having an awareness of which client is due in for an appointment and the animal they are bringing can help make the ‘booking in’ process more personal. For clients coming in for advice without an appointment, quickly establishing who they are and the type of advice needed allows the client to be seen promptly by the correct member of staff.

If the client is waiting for an appointment, the front of house team should keep the client updated on waiting times. Emergencies can occur at any time, many clients are understanding of this but having options available such as re-scheduling appointments or offering a tea/coffee can help reassure the client they have not been forgotten about.

If parasite advice is being given via a nurse clinic or appointment (pre-booked or walk-in), prior to calling the client into the room the VN should ensure the room is clean and tidy and that they are familiar with the pet's clinical history. It is imperative the client feels the VN is prepared for the consultation. The VN should have a clean and tidy appearance, with long hair tied back and a name badge should be worn (Ackerman, 2012). When the VN calls the client into the room, again a personal approach should be adopted, calling the client in by the patient's name is preferred to using surnames. Ackerman (2012) and Faulkner (2017) assert making a fuss of the pet and using the pet's name helps show the client that the VN cares about their pet.

Some clients may call for advice over the telephone, in many cases this call will be taken by the front of house staff and then transferred to the VN for advice. Front of house staff should obtain the client and pet's name and the reason for calling so the VN can then greet the client by name, enabling a personal approach to still be adopted. While communicating over the phone consideration should be given to tone of voice; this should be kept light and friendly.

Body language

Consideration should be given to body language and other non-verbal methods of communication. The VN should adopt an open body position with arms by the side of the body rather than crossed in front of the body. Hand gestures may be used to emphasise points. The facial expression used should be pleasant, the VN may not agree with some of the client's opinions but this should not be revealed within the facial expression. Eye contact should also be made with the client, although some VNs or clients may find this uncomfortable initially. There should be no barriers between the client or the VN so the positioning of the table within the room (if applicable) and computer screen needs to be well thought out. If the client chooses to sit it is advised that the VN also sits down so communication is at the same level and eye contact can be made.

How to question the client and what to ask

A detailed history should be obtained from the owner. Many clients offer the VN information, it is important the client is given the opportunity do this but that the VN also directs the client to disclose the information required to identify parasite risk and therefore formulate a control plan. This is performed through careful use of both open and closed questioning (Ackerman, 2012; Loftus, 2012). Questioning in this manner not only allows information to be obtained but also builds rapport with the client, which is essential for good compliance.

The following questions are examples (not an exhaustive list) of what should be asked:

Listening closely to the client and showing a genuine interest in what they have to say is just as important as asking the correct questions. A client who feels their opinions are valued is more likely to utilise advice given (Ackerman, 2012; Loftus, 2012). Active listening is a helpful technique for ensuring the client and VN both understand what the other is saying. The VN asks a question and then repeats the client's answer back to them to ensure the meaning has been understood, the client then has the opportunity to expand on their answer as needed (Loftus, 2012).

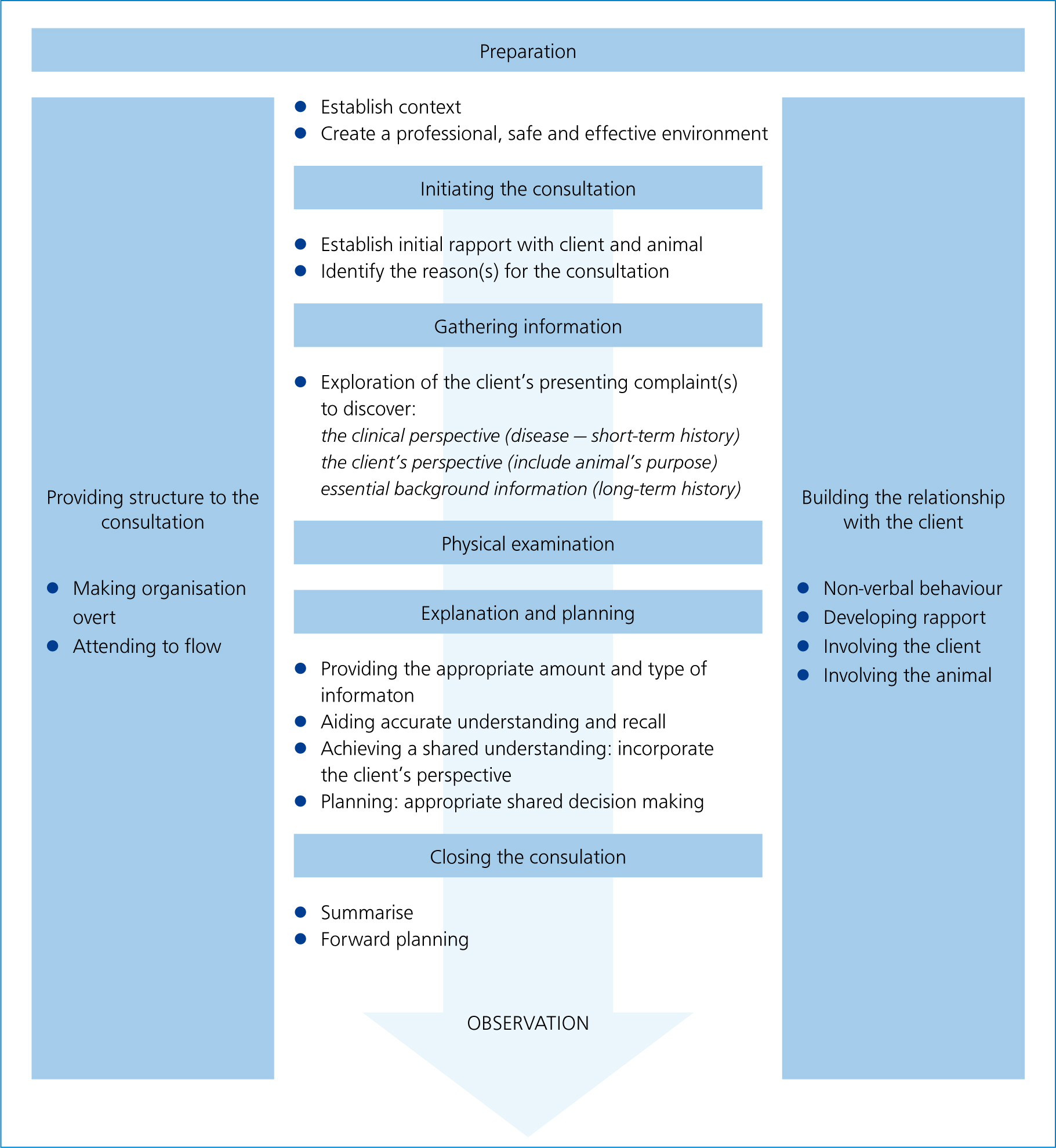

Figure 6 shows the Cambridge-Calgary consultation model which has been adapted by the National Unit for the Advancement of Veterinary Communication Skills, which makes it relevant for use by veterinary professionals (Ackerman, 2012). The model can help the VN utilise active listening as it provides a framework/structure for gathering information, exploring it and summarising it to the client (Wiggins, 2016). Wiggins (2016) states utilising a model in this way enables client communication to be structured, however, a personal approach should still be adopted.

Avoiding the use of medical jargon

Compliance can be increased by avoiding the use of technical/medical terms and Latin names for parasites (Wiggins, 2016). A simple description is often more effective and the use of diagrams and pictures to explain lifecycles enables the client to understand the need for different stages of prevention, e.g. treating both the patient and house for fleas.

Client learning styles

There are a number of different learning styles; visual, auditory and kinaesthetic (MindTools, 2017). To increase compliance using a variety of teaching methods to deliver information can be beneficial. Different techniques may involve:

It may not be appropriate to discuss learning styles with clients or ask what their style is (they may not be aware) but adopting a range of teaching techniques may benefit client compliance and bonding/rapport.

The 7Cs of communication

Improved communication can help to improve client communication and compliance and subsequently the health and welfare of the patient. Hedberg (2016) discusses the 7Cs of communication which can be considered with reference to the veterinary setting:

VNs should be aware of their own strengths and weaknesses when communicating with clients and should aim to improve these via practicing and obtaining advice or training.

Examining the patient

Regardless of the method used to deliver parasite advice the pet should undergo a thorough clinical examination. If any abnormalities are detected the patient should be referred to a veterinary surgeon for further examination (Orpet and Welsh, 2011). The patient's weight should be recorded to ensure accurate dosing.

Compliance

Client compliance is vital for the success of parasite prevention, parasite control plans will fail if clients are non-compliant. Elsheikha (2017b) states there are several factors that can lead to poor compliance including:

Having an understanding of these factors enables the VN to overcome them and achieve a positive change in client attitude with a resultant benefit to the pet. Developing a partnership with clients and involving them in every stage of the decision-making process allows the formulation of the control plan to be a mutual decision, increasing compliance and client satisfaction (Elsheikha, 2017b).

The VN's role does not end after advice has been given and the client has left with a suitable product. The VN must regularly meet with the client to evaluate and review the control plan to ensure it is up to date and compliance is achieved (Elsheikha, 2017b).

Information resources

For up to date parasite forecasts and advice for both veterinary professionals and clients the reader is directed to the UK and Ireland branch of the European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP). ESCCAP also have waiting room displays highlighting the parasite risk to clients which can be downloaded (www.esccapuk.org.uk).

Available from Veterinary Prescriber is an online module on Angiostrongylus vasorum aimed at veterinary staff (www.veterinaryprescriber.org).

Conclusion

Parasite control plans are growing in popularity due to the increasing parasite threat both in the UK and abroad and due to the risk of disease to pets and zoonosis in humans. The VN plays an integral role in implementing individualised parasite control plans and educating clients on the importance of adequate control, the benefits to the pet and how to employ suitable control measures and administer prophylactic treatments. The VN can deliver advice to clients in a variety of settings. Developing a partnership with clients so control plans are a mutual decision increases compliance and satisfaction for the client and VN.