References

Use of broad-spectrum parasiticides in canine and feline parasitology

Abstract

Companion dogs and cats are exposed daily to several internal and external parasites, and to pathogens transmitted by arthropods. Efficacious prophylactic and therapeutic measures are of paramount importance to controlling the occurrence and diffusion of parasitosis and arthropod-borne diseases, as well as protecting both human and animal health. Several broad-spectrum parasiticides are available on the market and represent a crucial tool for the treatment and/or prevention of several canine and feline endo- and ecto-parasites.

Dog and cat health can be threatened by several parasitic diseases caused by intestinal and cardiorespiratory helminths and vectorborne pathogens. A plethora of antiparasitic products is available on the market and several broad spectrum parasiticides allow the control of both endoparasites and arthropod vectors of dogs and cats. Thus, an all-round knowledge of the biology of parasites and their vectors is pivotal to choose and use these molecules properly.

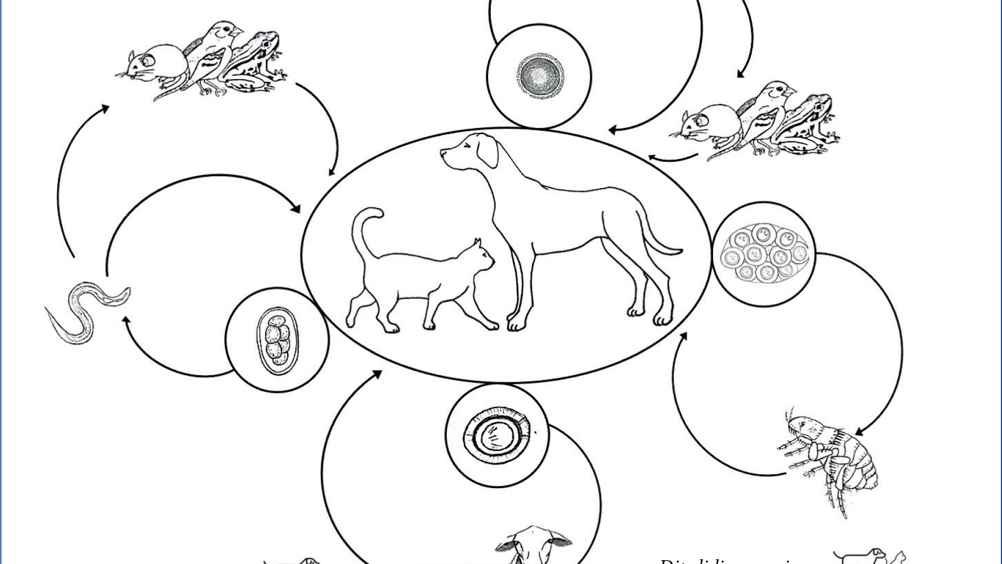

Intestinal helminthes of companion animals are of primary importance in daily clinical practice (Figure 1). The roundworms (ascarids), Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati (Figure 2), infecting dogs and cats respectively, are the most common intestinal parasites of dogs and cats worldwide (Overgaauw, 1997; Epe, 2009; Traversa, 2012), while Toxascaris leonina (infecting both dogs and cats) is less distributed. Vertical transmission, resistance of the eggs in the environment, number of eggs produced by adult females and availability of paratenic hosts, are a winning strategy for the spread of ascarids. Adult animals suffer from intestinal distress, while puppies and kittens also show ‘pot belly’, poor growth, vomitus and/or diarrhoea with frequent expulsion of adult worms still alive and viable. Heavy infections cause potentially fatal occlusions, intussusceptions and perforations (Epe, 2009). Ascarids represent a threat to humans, who become infected by ingesting Toxocara larvated eggs from the environment. Especially in children, Toxocara spp. causes the so-called visceral, ocular and cerebral larva migrans syndromes (Robertson and Thompson, 2002). Numerous green areas and playgrounds in suburban and urban contexts are highly contaminated with roundworm eggs, which become infective from 2–6 weeks after their emission in the environment (Traversa et al, 2014).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.