References

CPD article: Weight loss considerations in the older cat

Abstract

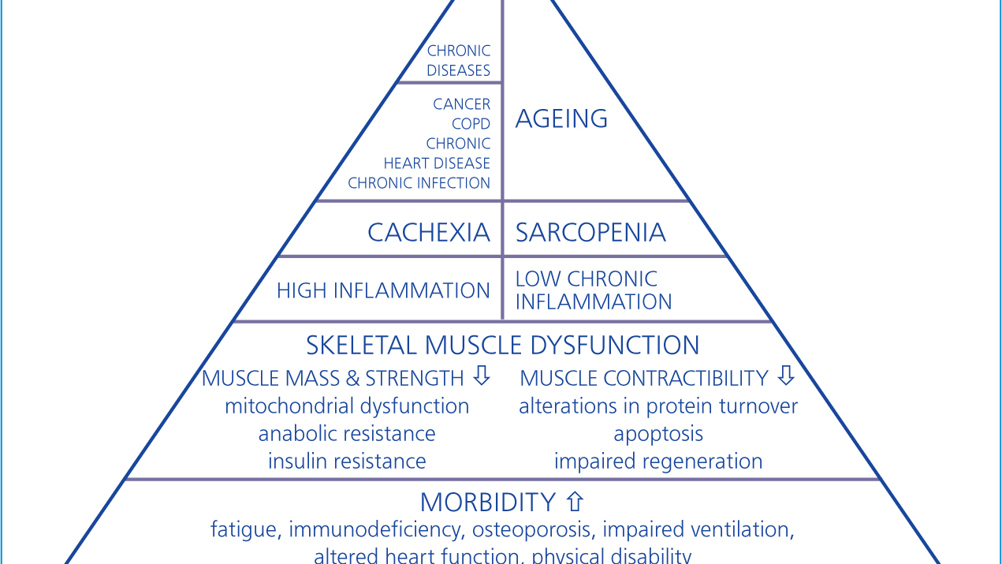

The companion animal population is continuing to live longer, with approximately 40% of pet dogs and cats aged 7 years or older. Continued improvements in veterinary care and disease prevention strategies, veterinary nutrition, breeding and husbandry are just a few of the factors contributing to pet longevity, resulting in a significant population of senior small companion animals. This article considers the most common causes of weight loss in the older cat through review of the definitions and pathophysiology of muscle loss, and examining the most common concurrent metabolic and endocrine diseases associated with weight loss in the older feline patient.

The average age of companion animals is increasing with approximately 40% of pet dogs and cats aged 7 years or older (Laflamme, 2012). Continued improvements in veterinary care and disease prevention strategies, veterinary nutrition, breeding and husbandry are just a few of the factors contributing to pet longevity, resulting in a significant population of senior small companion animals (Day, 2010; Biourge and Elliott, 2014; O'Neill et al, 2015).

Cats are considered ‘senior’ at 11–14 years old and ‘geriatric’ at 15 years and above (Caney, 2009), and while age itself is not a disease, special consideration should be given to this when they present for consultation as increased age is associated with a decline in organ function and immune response, as well as the development of physiological changes (Lumbis, 2018). 15% of cats over 12 years of age have a low body condition (Armstrong and Lund, 1996) and after 14 years of age, cats are at 15 times greater risk for being underweight (Courcier et al, 2012).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.