Nutrition is a broad subject, so this workshop looked at why nutrition is important and how veterinary nurses can weave nutrition into every conversation that they have with their clients.

Good nutrition can help to prevent problems, help with the management of certain conditions, help to increase life expectancy and promote good wellbeing and growth. In contrast, poor nutrition can create disorders, such as cleft palates, can impair the immune system, which means that recovery and healing can take longer (whether it is a broken leg, major abdominal surgery or kennel cough), and can lead to toxicities, deficiencies (such as rickets and scurvy) and illness.

In the UK, there are lots of technicalities about the terms which are used, so nutrition and nutritional supplements cannot be used for the treatment of conditions, but they can be used to help in the management of conditions.

An example is a renal diet. Controlling phosphate levels for renal patients can help extend life, on average their life-span is 2.7 years, so it is really important in this group to increase life expectancy. This is also the case for cardiac patients, cancer patients or obese patients – keeping these animals lean and promoting good wellbeing, good growth and a good body condition score can increase life expectancy. Good nutrition is really important in the overall health and wellbeing of the animal.

Pets should receive good antioxidants, proteins, vitamins and minerals to help boost the immune system. If puppies are given dehydrated colostrum in their diet this boosts the immune system to such a degree that when they are vaccinated, it increases the vaccine titres and the antibodies they produce and helps the efficiency of the vaccine.

What is preventative medicine?

Preventative medicine (which does not just include nutrition) can be subdivided into three parts:

- Primary prevention focuses on preventing disease before it develops (eg vaccination, flea treatments, wormers, preventing obesity)

- Secondary prevention attempts to detect a disease early and intervene early (eg preanesthetic blood tests, senior clinics)

- Tertiary prevention is directed at managing established disease in an individual and avoiding further complications (eg monitoring blood pressure in cardiac patients, renal patients, diabetic patients so that we can promptly treat hypertension if it starts to develop; dental care).

This article now looks at how nutrition fits into each part of this approach, and why veterinary nurses need to be talking about nutrition in every single consult.

Primary prevention

Examples include:

- Vaccines

- Fleas, ticks and wormers

- Keeping at an ideal body condition score

- Staying fit – talking to owners about how much exercise their pet is getting during every consult

- Eating the right foods

- Neutering (this can prevent pyometra, mammary tumours and prostate issues, but it predisposes the animal to higher weight gain)

- Dental hygiene.

Risk factors and preventative nutrition

- Breed of the pet

- Age of the pet (weight gain in dogs is quite linear, whereas cats are most likely to become obese in middle age, but then become underweight as they become older)

- Environmental aspects (where the pet lives and works if applicable)

- Who the pet lives with (humans and other animals).

The narrative of the animal and owner is important – understanding and knowing their back story gives a better understanding about the best care plan for the animal. For example, who lives with the animal, what do they like when they are out for a walk, can they be let off the lead? This narrative medicine allows care to be personalised for the specific animal and owner.

Obesity risk factors

The author's practice took the body condition scores for all animals for 10 years and found the following regarding the risk of obesity:

- Gender – females are more likely than males to be overweight or obese (odd ratio 1.49; P<0.001)

- Age – risk increases with age in dogs (odds ratio 1.07; P<0.001)

- Breed – highest occurrence of being above the ideal body condition score (3/5) was in hounds; and larger breeds were less likely to be overweight than smaller breeds (in a semirural setting). The breed significantly more at risk of being above the ideal body condition score is the King Charles Cavalier Spaniel (5.17 times more likely to be overweight than a crossbreed dog) followed by the smaller breeds (such as Border Terriers, Chihuahuas, cockers, dachshunds, Jack Russell Terriers). So if any of those breeds come in, particularly if they are female, we really need to talk to that owner about prevention of obesity.

The amount of energy that dogs require does not decrease as they get older. They are really good at digesting their food, whereas older cats are less good at digesting their food. A study found that dogs that were kept leaner lived 1.7 years longer than those that were allowed to eat whatever they liked.

Neutering

Neutering alters the metabolism. In work from the author's practice looking at the whole population of dogs in Plymouth over 10 years, 75% of dogs that were overweight had been neutered.

Once cats and dogs have been neutered, their metabolism will have dropped by 25–30% within 48 hours, so 25–30% fewer calories that are needed, almost overnight. Owners need to be made aware of this drop during post neuter appointments and at discharge, so that they understand about adapting the diet accordingly.

Post-neutering clinics

Dogs that had been neutered were invited to a postoperative neuter clinic, 3 months post surgery and their weight was monitored for 5 years. Every time a neutering surgical procedure was booked, the system generated a reminder that went out 3 months later and the animal came back in. This is a really good opportunity to monitor weight – they are normally about 9 months of age at this point. The animal is usually transitioning from a puppy diet over to adult food depending on the breed. If the animal is not seen then, they are unlikely to be seen until about 15 months of age for the first annual vaccination. Every animal is weighed and has a body condition score done.

Looking at the figures from this practice, neutered female dogs that did not attend the clinic had a prevalence of 9.25% having a body condition score greater than ideal, whereas in those who came in and saw the nurse 6.77% had a body condition score greater than ideal. None of those that came to the nurse clinic had a body condition score of 4.5 or 5, so there were no obese animals at all.

These animals were followed up for 10 years and those that came in and saw the nurse more regularly and were weighed more regularly had a prevalence of obesity half that of those that were not regularly seen and weighed.

Weighing animals each time they come in and making a nutritional recommendation is a simple intervention that could halve the number of obese animals.

Secondary prevention

Screening nurse clinics fit into the category of secondary prevention. Senior or wellness healthcare screening, blood pressure monitoring and yearly urinalysis are all examples where attempts are made to detect a disease early in order to intervene early and improve overall clinical outcomes.

Even if the owner does not want to go down the route of diagnostics (eg urinalysis, blood pressure measurement, blood tests) because they feel their pet is well, weighing the pet regularly can be a form of secondary prevention because weight loss is a very early indicator of disease for lots of conditions.

Screening through nutritional assessment

Screening the animal and weighing them is part of nutritional assessment. Before starting any form of nutrition a full assessment of the animal is necessary, with a full clinical history and assessment of the current health status. Nutritional assessment is one of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association five vital assessments, along with temperature, pulse, respiration and pain scoring.

When weighing the animal it is important to use scales that are appropriate for the size and species of the animal being weighed, so cat scales are really good for small dogs as well. Older scales often only go up in 100 g increments, which is not accurate enough if weighing a small dog or a cat, and some do not measure above 100 kg.

Body condition score

At this point, the animal should also have the body condition score done and recorded, along with looking at the individual animal, including the frame and feeling the animal. The nine point body condition score has been scientifically validated and this is what should be used.

Interestingly, if the nurse is emotionally attached to the animal that they are body condition scoring, that will influence the reading obtained. Work by a nurse from New Zealand showed that owners cannot reliably body condition score their own pets although they can reliably body condition score other people's pets – there is a bias there.

Accurately scoring animals

Churchill (2019) produced a useful diagram which is worth studying to make sure that the nurse knows how to actually feel for the ribs and part the hair properly, so they can see the skin and then feel the ribs, shoulders and hips.

Muscle condition score is also needed for senior animals to evaluate muscle mass. This includes visual examination and palpation over the temporal bones, scapulae, ribs, lumbar vertebrae and pelvic bones.

Marked muscle wastage is seen as an animal gets older because they are not exercising as much – there is this misconception that animals should not exercise as they get older. Body condition scoring and weighing the animal is important to show patterns of weight change.

Studies in cats have demonstrated an increased incidence of obesity with increased age up to 11 years, but after this peak a loss of body mass, fat and lean tissue tends to be seen. Cats need higher amounts of energy moving into this senior stage because of changes in the way that they digest their foods – they need higher energy and higher digestibility food. The speed of decline in body weight can be a predictor of mortality, with progressive decline in body weight reported in the 2 years before death. When weight loss is noted, particularly quick weight loss, the cat needs to be referred back to the veterinary surgeon to see why they are losing weight. It could be that they need a higher energy food, or it could be that they have hypothyroidism or renal disease.

Nutrient requirements

The energy requirement for senior cats can increase once geriatric stages are reached. Senior diets on the market differ depending on the viewpoint of the manufacturer. There are no written guidelines for the nutritional requirements of senior cats and senior dogs which makes things difficult.

FEDIAF have produced statements on senior nutrition with some recommendations, but there are no guidelines for senior pets. The requirements within this life stage vary much more than within any other age range, so nurses need to give personalised recommendations based on each animal's requirements.

Traditionally senior pet foods were quite restrictive on protein requirements, so senior pet food used to be lower in calories, protein and salt. Now it is clear that some senior cats need more energy than they did in kittenhood. So a lot of senior diets are now higher in calories, but are not restricting protein levels. This is important because cats have more impaired digestion and do not absorb protein as well as they get older so they need more good quality protein in their food. Protein requirement for senior cats is higher with increased protein turnover and reduced protein synthesis.

The important thing is the individual assessment, looking at each animal as an individual and making a nutritional recommendation based on that.

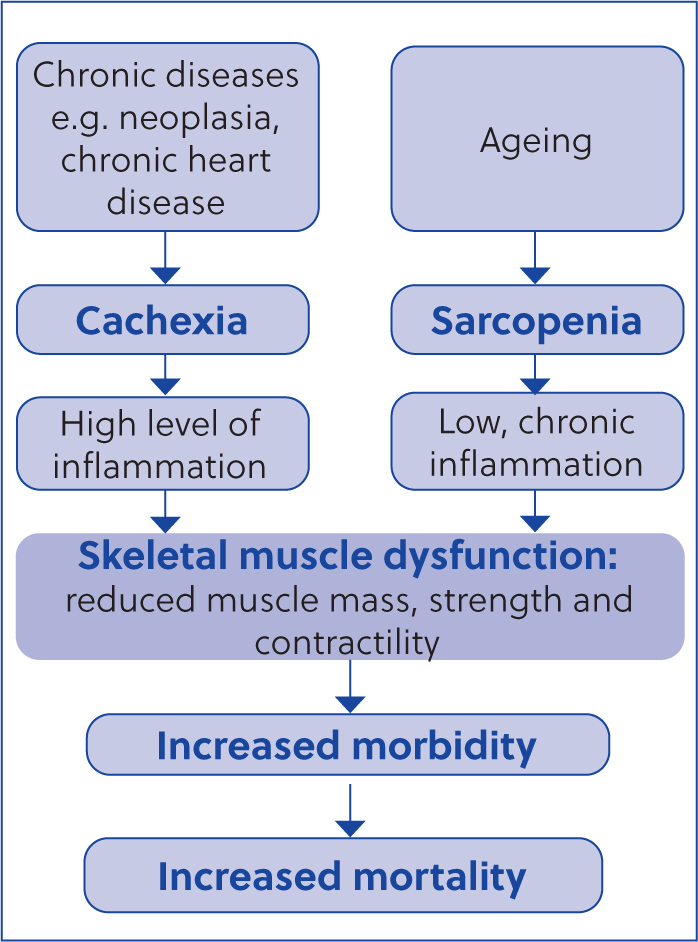

Figure 1 shows how sarcopenia and cachexia develop. When cats start losing weight, they develop sarcopenia, losing muscle mass and increasing morbidity and then mortality. So good nutrition that they can metabolise, digest and absorb is really important and there are some foods that really help combat cachexia. During cachexia there are really high levels of inflammation, so essential fatty acids are vital for this. Cardiac patients and renal patients especially need high levels of essential fatty acids because these help maintain body mass and combat other illnesses.

Tertiary prevention

Tertiary preventative healthcare tries to prevent deterioration in animals that have already been diagnosed with a condition, eg using phosphate binders in renal patients or essential fatty acids in cardiac patients. These are mainly managing the clinical signs, and in terms of nutrition mainly looking at weight loss, body condition score and muscle condition score and preventing them from getting any worse.

Consensus statements provide evidence-based recommendations for management, for example for mitral valve disease discusses controlling blood pressure, use of medications, sodium levels in diets and exercise, or IRIS renal staging which gives recommendations regarding phosphate levels at certain stages, diet, blood pressure control.

Cardiac changes and senior diets

A good example is the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement for myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs (Keene et al, 2019), seen in a lot of Cavaliers in the UK. They staged mitral valve disease to describe four basic stages of heart disease and heart failure (Table 1).

Table 1. American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine stages of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs and nutritional recommendations

| Stage | Category | Clinical signs | Nutritional recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Predisposed | No clinical signs | Advise owners about high sodium treats and human foods |

| B1 | Appears healthy (heart murmur likely, no cardiac remodelling) | No clinical signs | Advise owner to avoid high sodium diets (more than 100 mg/100 kcal) high salt treats and human food |

| B2 | Appears healthy (heart murmur and evidence of cardiac remodelling) | No clinical signs | Dietary sodium content of 50–80 mg/100 kcal and avoid high salt foods as above |

| C | Current or previous heart failure | Clinical signs of heart failure | Sodium content less than 50 mg/100 kcal |

| D | Heart failure refractory to treatment | Clinical signs of heart failure | Diet changes not done while dog is in hospital |

Knowing the stage that the dog is at allows them to be monitored and give medication as necessary, such as pimobendan to treat heart failure or amlodipine to treat hypertension. Table 1 gives nutritional recommendations for the different stages, that mainly relate to sodium intake in the diet. Despite them having heart disease, exercising these animals increases their physical fitness, which has other benefits such as decreasing their respiratory rates.

Phosphate

Waltham Science Institute demonstrated a new safe level of phosphorus in feline diets (1 g/1000 kcal of inorganic phosphorus and either 4.0 g/1000 kcal or total dietary phosphorus in combination with a calcium:phosphorus ratio of 1.0, or 5.0 g/1000 kcal or total dietary phosphorus in combination with a calcium:phosphorus ratio of 1.3), as phosphorus may contribute to chronic kidney disease in cats.

Not all phosphate salts are the same – while limiting the use of highly soluble phosphates appears to be important, there are insufficient data to support a specific upper limit for phosphate intake.

Prevention is better than cure

To highlight the scale of the impending issue, in 2018, the Pet Food Manufacturers Association (now called UK Pet Food) estimated that there were 9 million dogs in the UK and 8 million cats. During the pandemic that increased to 12 million dogs and 12 million cats. Initially veterinary practices saw a lot of puppy and kitten vaccinations, which have dropped off as traditionally animals tend not to be seen much between that first year of life and when things start to go wrong when they are a bit older.

It is important for veterinary nurses to discuss prevention at all points, weaving nutrition into all of those consultations. Puppy and kitten clinics are an ideal place for these, but it is also important to build up the owner's expectation of seeing the nurse regularly. One option is to take baseline bloods at a young age because these can provide a very useful comparison for the middle-aged and senior geriatric years.