Communicating with owners of animals approaching the end of their lives is a challenge that veterinary surgeons, veterinary nurses and reception staff will face. Research conducted in Canada by Adams et al (2000) stated that 70% of veterinary clients are emotionally affected by the death of their pet, further stating that as many as 30% of clients experience severe grief in anticipation of or after the death of their pet. The content, duration, and methods of end-of-life communication in both the veterinary and veterinary nurse curricula are highly diverse and variable (Shaw and Lagoni, 2007), with much of the training focussing primarily on post-euthanasia support. While post-euthanasia support is a valuable service for clients, end-of-life care frequently requires owners to make decisions of monumental consequence prior to the death of their pet, at a time when they can feel they sorely lack vital support (Shanan, 2011). It seems prudent to suggest therefore, that where the loss can be anticipated, as is the case with terminally ill patients, support for the client should begin prior to the actual loss.

Why do owners require support?

The moment of recognition that a cure is unattainable defines the beginning of palliative or hospice provision in an animal's care. When highly-bonded pet owners acknowledge this moment, it is normal for them to experience intense emotions, generally termed anticipatory grief (Shanan, 2011). During this phase, people realise that their present circumstances hold the potential for the loss of their pet and, even before the animal dies, they begin to display symptoms of grief (Lagoni and Hetts, 2012). How a pet owner's anticipatory grief is managed can have a strong impact on the grieving process and subsequent healing process after a loss.

The role of veterinary personnel in helping clients make decisions about their pets' end of life will invariably involve discussion regarding the option to intervene and end a patient's suffering by the act of euthanasia; this is a significant and unique difference between human and pet bereavement.

Despite on-going and controversial ethical debate, with a few exceptions, for example The Netherlands, human euthanasia is illegal throughout most parts of the world. Euthanasia-related grief is distinct because it involves making an active choice to end the life of a treasured companion and accepting personal responsibility for this decision (Dawson, 2013).

Pet owners have to make decisions while experiencing the intense emotions of acute grief. Such decisions can greatly influence some owners' subsequent grief and the healing process, therefore before engaging in conversations regarding euthanasia it is beneficial to gain a basic understanding of the normal grief responses and processes.

Understanding grief

Many veterinary personnel will be familiar with the five stages of the grieving process, namely, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance Table 1 which although designed for human loss are often applied for understanding grief reactions to pet loss.

| Denial | This is usually only a temporary defence for the individual. This feeling is generally replaced with heightened awareness of the situation and a feeling of being left behind after the death. A discussion about death cannot occur during this stage and in fact a client may seek a second opinion after the diagnosis of a terminal prognosis |

| Anger | This stage often occurs once the individual recognises that denial cannot continue. Due to feelings of anger and frustration, an individual can be difficult to communicate with during this stage due to misplaced feelings of rage and envy |

| Bargaining | This stage involves the hope that the individual can somehow postpone or delay death. Veterinary clients may ‘bargain’ for more time for their pet, alternative medications or may even offer gifts to veterinary personnel in exchange for a cure |

| Depression | During this stage, the individual begins to understand the certainty of death. Because of this, they may appear withdrawn, become silent and spend much of their time crying and grieving. It is not recommended to attempt to make plans or “cheer up” an individual who is in this stage as this is an important time for grieving that must be processed |

| Acceptance | In this stage, the individual begins to come to terms with the impending death and discussion surrounding the final weeks/days can often take place |

The five stage model was first introduced in 1969 by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross in response to her frustration at the lack of curriculum in medical schools on the subject of death and dying. While this model may be widely recognised, it is often misunderstood and perceived as a linear process with individuals experiencing grief expected to begin in the denial stage and progress through each stage in order, towards the ultimate goal of acceptance. Grief however is not a linear process; it involves complex emotions that cannot be neatly categorised and the lived experience of grief is frequently chaotic and undulating. Dawson et al (2008) stated that companion animal bereavement never occurs in a vacuum, but within the wider landscape of the owner's life, being shaped by other co-existing or past losses such as ageing, chronic ill health, human bereavements and other companion animal losses. Clients' reactions to grief may appear overly intense at times, but it is essential that veterinary personnel see each client as an individual and remember to view their reaction to the loss of a companion animal as contextual. For some clients, grief arising from pet bereavement will be minimal and resolve quickly; for others, however, it can be more protracted, painful and complex.

Rando (1984) stated that when the expression of grief is restricted, the healing period of recovery is prolonged, however when grief is freely expressed the healing time for recovery from loss is greatly reduced. This finding highlights the role veterinary personnel have in helping clients to better cope with the death of their companion, by actively encouraging open expressions of grief and by empathising with their situation (Adams et al, 2000).

Why does death need to be discussed?

Many veterinary personnel find end-of-life discussions challenging for a number of reasons, including a lack of sufficient training, time constraints, practice culture, impact on the veterinary-client-patient relationship and concerns about the client's emotional response (Buckman, 1992).

Extrapolating from evidence in human medicine, when end-of-life conversations are conducted skilfully they have the potential to validate and provide support for clients facing difficult decisions. When these are poorly executed however, they have the potential to lead to dissatisfaction with veterinary personnel or overall veterinary care, a reduction in client compliance and retention and the potential to complicate grief (Rosenbaum et al, 2004). Indicators of complicated grief include a prolonged period of grieving, intense responses, and interference with physical or emotional wellbeing (Glass, 2005). Clients displaying a complicated grief reaction may benefit from referral to a dedicated bereavement support professional sensitive to the needs of those grieving the loss of a pet. A valuable veterinary bereavement resource for all UK veterinary clients, however, is the Blue Cross Pet Bereavement Support Service (PBSS) which operates a telephone support service staffed by volunteers who have personally experienced pet loss. The service is available by telephone on 0800 096 6606 (8.30 am–8.30 pm).

Conducting a pre-euthanasia discussion

In veterinary medicine, the primary goal of end-of-life decision making is ensuring quality of life during the treatment or palliative care phase, and ultimately a peaceful, timely death for the patient. Making end-of-life decisions is associated with anxiety about death itself, but also financial implications and the uncertainty of facing the future without a treasured companion. Guilt is commonly experienced by clients when facing the loss of a pet by euthanasia; this often stems from owners' perceptions that they have failed in their responsibility to keep their companion safe, healthy, and alive (Lagoni et al, 1994). Dawson (2007) defined this this as ‘responsibility’ grief, caused by owners struggling to accept and accommodate their personal responsibility for the death of their companion by euthanasia.

Discussion prior to the actual euthanasia of a pet can be extremely helpful in lessening feelings of responsibility validating decisions and enabling owners to know they did their best for their companion. The aim of a pre-euthanasia discussion is to clarify the client's wishes regarding the pet's death, help to minimise regrets about how the death was handled, and to enable the client to better cope with the death of their companion (Shawand Lagoni, 2007). Forpre-euthanasia discussions to be beneficial, Shanan (2011) suggested it is essential to listen to what is most important to a family facing the prospect of euthanasia for their companion. This includes finding out what their concerns are, how they want to spend their time as their options become limited, and what kind of compromises they are prepared to make, prior to offering further information and advice. Conversations such as these are frequently undertaken in veterinary practice, however this is often all that is discussed until the actual euthanasia takes place. It is imperative that wherever death can be anticipated, as is the case with hospice patients, details about the active dying process, quality of life and euthanasia, including such details as where the process should take place, who should be present, and after-death body care options should be discussed ahead of time with clients.

Shanan (2011) stated that when a companion animal is actively dying or when a decision has been made that euthanasia is necessary, it is essential that an owner should be in a position to exercise control over the physical and social environment that surrounds their beloved companion during the last moments of life. Veterinary personnel can educate owners by providing information about potential options and during pre-euthanasia discussions can encourage owners to formulate a plan in advance. This enables veterinary personnel to facilitate decisions at the time of crisis by reminding owners of the plans they have already made and/or guiding them towards options that the veterinary team believe are consistent with the owner's values.

For veterinary hospice patients, regular visits will reveal decreasing quality of life and pre-euthanasia discussions will often follow as a natural extension of hospice care. However, for all scheduled euthanasias, veterinary personnel have the opportunity to discuss how owners would like to proceed. Timing of such a conversation can be difficult to judge, however a study conducted in Switzerland by Fernandez-Mehler et al (2013) revealed that 68% of the veterinary clients they surveyed had thought about pet loss during their animal's life. Furthermore, nearly 90% expected veterinary staff to talk about the after-death body care of their pet, with 38% of clients expecting this to happen prior to approaching the end of the pet's life. While it is certainly difficult to discuss the topic of death without actual reason, this study highlights that this is exactly what some clients may wish to do. One possible solution may be to have information material available in the waiting room with the invitation for clients to seek additional advice and information if they wish.

A pre-euthanasia meeting helps orchestrate a humane, family-centred euthanasia. When time permits, the visit can help clients prepare for the procedure, make informed decisions, and even complete financial transactions in advance if they wish. The aim is that when the time arrives for the euthanasia, all the client has to focus on is their pet.

A pre-euthanasia discussion must include discussion of what will actually happen during the euthanasia; explaining the protocol while clients are thinking clearly makes the procedure less frightening (Ruby, 2010). It is important to clarify clients' current understanding of the procedure and to listen for any information they may want to share or questions they may have. It is essential to explain how the euthanasia solution will work, and how quickly it can take effect. While distressing to hear, it is necessary for clients to be informed about such things as bladder and bowel movements, muscle tremors and agonal respiration. Such reactions are far more distressing to clients if they do not know to expect them.

Owners may envisage holding their pets in their laps or cradling them in their arms. Often the reality, however, is the pet is surrounded by veterinary personnel raising veins and administering medications; this can leave owners feeling ‘shouldered out’ of their own pet's euthanasia (La Jeunesse, 2012). Such a situation can be avoided by placing an intravenous catheter into either the cephalic or saphenous vein for drug administration during owner-present euthanasias. Such a procedure will enable appropriate delivery of the required drug but will also facilitate different ‘staging’ scenarios for how clients and staff can be physically positioned during the procedure (La Jeunesse, 2012).

Family present euthanasia

A number of options are available regarding who is present during an animal's last moments and immediately after death. While some clients feel they must be alone, it is increasingly commonplace for clients to request other family members to be present during euthanasia, a fact which reinforces the role of pets as treasured family members. This can raise the difficult issue of whether children should be present during the euthanasia procedure. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the in-depth detail surrounding children and pet loss; the following discussion is intended as a starting point only. It is essential to remember that children vary in their sensitivity their resiliency and in their attachment to their pet, so each case must be dealt with individually.

Only the parent or guardian of the child can ultimately make the decision as to whether a child should be present during the euthanasia process, however veterinary personnel may be called on to give guidance. Many parents feel the need to protect their children from the sensitive issue of death, however not talking about it or not telling the truth does not help a child to learn to cope with loss, which is an inevitable fact of life (Argus Institute, 2011). When discussing death with children, explanations should be simple and direct. The child should be told the truth using as much detail as they can understand. If the decision is made to allow a child to be present during euthanasia, they must have a complete explanation in advance of what they will see, so that there are no surprises (Exceptional Veterinary Team, 2014). Where the death can be anticipated, as is the case with terminally ill pets, preparation for death should begin prior to the actual loss. A number of resources are available to help with this preparation such as the Missing my pet book written by 6-year-old Alex Lambert after the death of his pet dog Star. The book explores the whole process of losing a pet, from the initial illness through to euthanasia and beyond. The book further explores other issues surrounding the death of a pet such as after death body care options and getting a new pet. The book also comes with a supporting booklet containing advice for parents. It may be advisable for veterinary practices to keep a small stock of such resources which can be loaned out to clients on request.

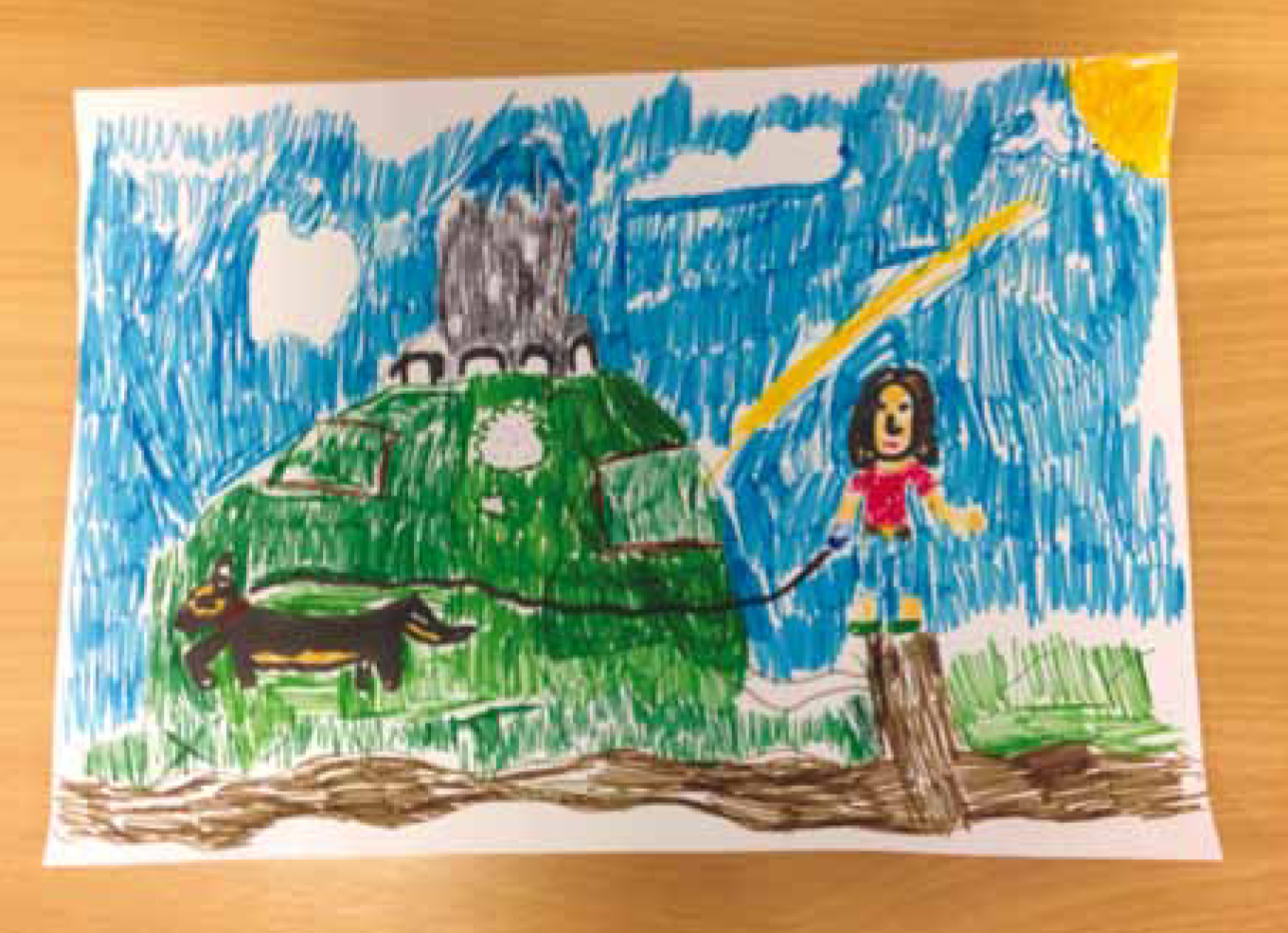

If the euthanasia procedure is considered too emotional for a child, having the opportunity to say goodbye before and after euthanasia may be considered. When death occurs, children can and should be included in the planning and participation of memorial ceremonies (Argus Institute, 2011). Such events can help children to say goodbye and give them the opportunity to understand the passage of death in a concrete way. Children can also be encouraged to express their grief by creating a memory box or scrapbook of photographs, or by drawing pictures of happy times together with their pet (Moga, 2012). Such images can be used by a veterinary practice to create a memorial wall which can be especially helpful to children as it enables them to honour their deceased pet which can be comforting if they return to the veterinary practice with another family pet.

Location

For communication to be effective, the right location is essential. Clinical environments can make clients feel uncomfortable so the provision of a ‘farewell room’ is a valuable asset for a veterinary practice; such a room should ideally be in a quieter location of the practice. To create an atmosphere of calm for both pet and owner, a number of features can be incorporated into such a room including walls decorated in a warm colour with framed prints replacing clinical posters, upholstered chairs, plants, calming aromatherapy oils such as chamomile or lavender and the provision of cushioned floor matting to facilitate floor-based euthanasia, an option increasingly offered in the United States where owners are allowed to get on the mat with their pet thus enabling them to be in close proximity during the animal's final moments. The placement of an intravenous catheter greatly facilitates this process.

Many veterinary practices will not have the luxury of space to dedicate to a farewell room, however thought should still be given to the location of pre-euthanasia discussions and the euthanasia procedure. Discussions should be scheduled for ‘quieter’ times of the day and the consultation room in the quietest area of the practice should be used. All staff must be aware of what the room is being used for; the sound of laughter and loud conversation outside a consulting room can be upsetting and is disrespectful to clients, especially if the disturbances are coming from veterinary staff (La Jeunesse, 2012). Moving the consultation table away from the centre of the room, and not standing directly behind it will all help to remove any ‘institutional’ feel to the room which may act as a barrier to communication. The physical proximity and the relative positions of the client and healthcare personnel in a room are known to influence interaction (Morgan, 2008). An experiment in which a cardiologist removed the desk from his office on alternate days indicated that the presence or absence of the desk had a significant effect on whether the patient was at ease or not. The findings highlighted that only 10% of patients were perceived to be at ease when the doctor's desk was present and the doctor was sat behind it. This figure increased to 50% when the desk was absent (Pietroni, 1976). Moving the consulting table to the side of the room instead of the centre and not standing directly behind it during discussions may make veterinary clients feel more at ease and thus more likely to discuss sensitive issues with staff.

Veterinary practice culture

Gorman et al (2005) stated that the veterinary practice culture influences whether end-of-life communication is valued by the veterinary team and thereby addressed, or overlooked. Ratanawongsa et al (2005) investigated the experience of third-year medical students dealing with dying patients. Their study identified role modelling, acknowledgement of the death, and interactions with team members as instrumental factors in skill acquisition and development of helpful coping mechanisms. Senior veterinary personnel are role models not only in demonstrating skills but also in fostering positive attitudes — how such key team members deal with challenging conversations and express their emotions towards death and dying may have an impact on how the rest of the team does. Promoting an atmosphere of collegial support, respect, and empathy serves as the foundation for providing care to clients and their pets (Shaw and Lag-oni, 2007). Just as with any other area of veterinary practice, it is necessary to involve the whole team in producing and adhering to bereavement support protocols.

It has been reported that veterinary surgeons are present at the death of their patients five times more often than other healthcare professionals (Hart and Hart, 1987; Villalobos, 2014). Williams and Mills (2000) stated that providing emotional support to pet owners contributes to stress among members of the veterinary practice team. This is in congruence with Mannette (2004) who stated that creating a practice culture that promotes self care and work-life balance is essential to preventing stress, compassion fatigue and burnout.

Conclusion

Pet owners have to make difficult decisions surrounding their pet's end-of-life care, while experiencing the intense emotions of acute grief. Such decisions will greatly influence some owners' subsequent grief and may prolong the healing process. The provision of euthanasia for companion animals places veterinary personnel in the unique position to anticipate the loss of a treasured companion and to assist owners by providing information about available options and by encouraging them to formulate a plan which suits them and their pet ahead of time. Shanan (2011) suggested that knowing they did their best with the information they had will enable owners to have an easier time forgiving themselves and ease any negative thoughts that the decision to end their pet's life was made a little too early or a little too late.