The operating room is one of the most hazardous environments in the healthcare delivery system. By definition, surgery is invasive. Instruments that are designed to penetrate patient's tissue can just as easily injure the provider. Blood is everywhere. Speed is essential. Emergencies can occur at any time and interrupt routines. Preventing injuries under these circumstances is challenging (Gerberding, 2001).

The operating theatre has certain characteristics that increase the likelihood of accidents. For example, staff frequently use and pass sharp instrumentation without looking or letting the other person know their intentions. Workspace may be confined and the ability to see what is going on in the operative field for certain members of the team such as the scrub nurse or surgical assistant may be poor. This is further complicated by the need for speed, not to mention the added stress of anxiety, fatigue and, on occasion, frustration (Tietjen et al, 2003). Sound familiar?

Sharps injuries

The vast majority of sharps incidents in human surgery occur in the operating theatre and most are due to scalpel and suture needle injuries, which is not surprising given that these are the two most frequently used sharps during operations (Tietjen et al, 2003).

Scalpel injuries

Scalpel injuries most frequently occur when:

Suture needle injuries

Suture needle injuries most frequently occur when:

Avoiding sharps injuries

Almost all of these injuries can be easily avoided with little expense by:

The ‘hands-free’ technique for passing surgical instruments

The safest method of passing sharp instruments during surgery is the hands-free technique. The rationale behind this technique is to reduce the frequency of hand-to-hand passes between surgical personnel as much as possible (Association of peri-Operative Registered Nurses (AORN), 2001). It is designed to be one way of ‘regularising’ the passing of sharp items to increase predictability among surgical personnel who may or may not regularly work together, who wear surgical masks, face shields and goggles which can distort communication and when gestures that would enhance meaning cannot be made (Stringer and Haines, 2006).

Although opinions regarding what constitutes a sharp item vary, there is a growing consensus that items eligible for passing using the hands-free technique include:

Using the hands-free technique, the assistant or scrub nurse places a sterile kidney dish or other suitable small container on the operative field between him/herself and the surgeon. A plastic container may be more suitable, as a metal container such as a kidney dish may contribute to the dulling of sharp instruments over time. This may be avoided, however, by lining the kidney dish with a sterile cloth (Figure 2). Commercially made hands-free devices are available to purchase; these include sharps passing trays and magnetic drapes.

Whichever container is used it is designated as the ‘safe or neutral zone’ in which sharps are placed before and immediately after use. The assistant or scrub nurse alerts the surgeon that a sharp instrument has been placed in the safe zone, with the handle pointing toward the surgeon, by saying ‘scalpel’ or ‘sharp”’ while placing it there. The surgeon then picks up the instrument and returns it to the container after use, this time ensuring the handle points away from him/her (Tietjen et al, 2003). An alternative way to perform the hands-free technique is to have the assistant or scrub nurse place the instrument into a container and pass it to the surgeon. The surgeon then lifts the instrument out of the container, which is left on the surgical field until the surgeon returns the instrument to it. The assistant or scrub nurse can then pick up the container and return it to the Mayo stand (Tietjen et al, 2003). Such a procedure requires the cooperation of all members of the surgical team and is dependent on a willingness to change long established routines and systems of working. Ford (2014) suggested role play and simulation could form part of training measures to highlight and promote sharp safety awareness amongst veterinary staff members.

Operating room fires

Thankfully fire in a veterinary operating theatre is a relatively rare occurrence, however the risks are quite high and the consequences can be devastating.

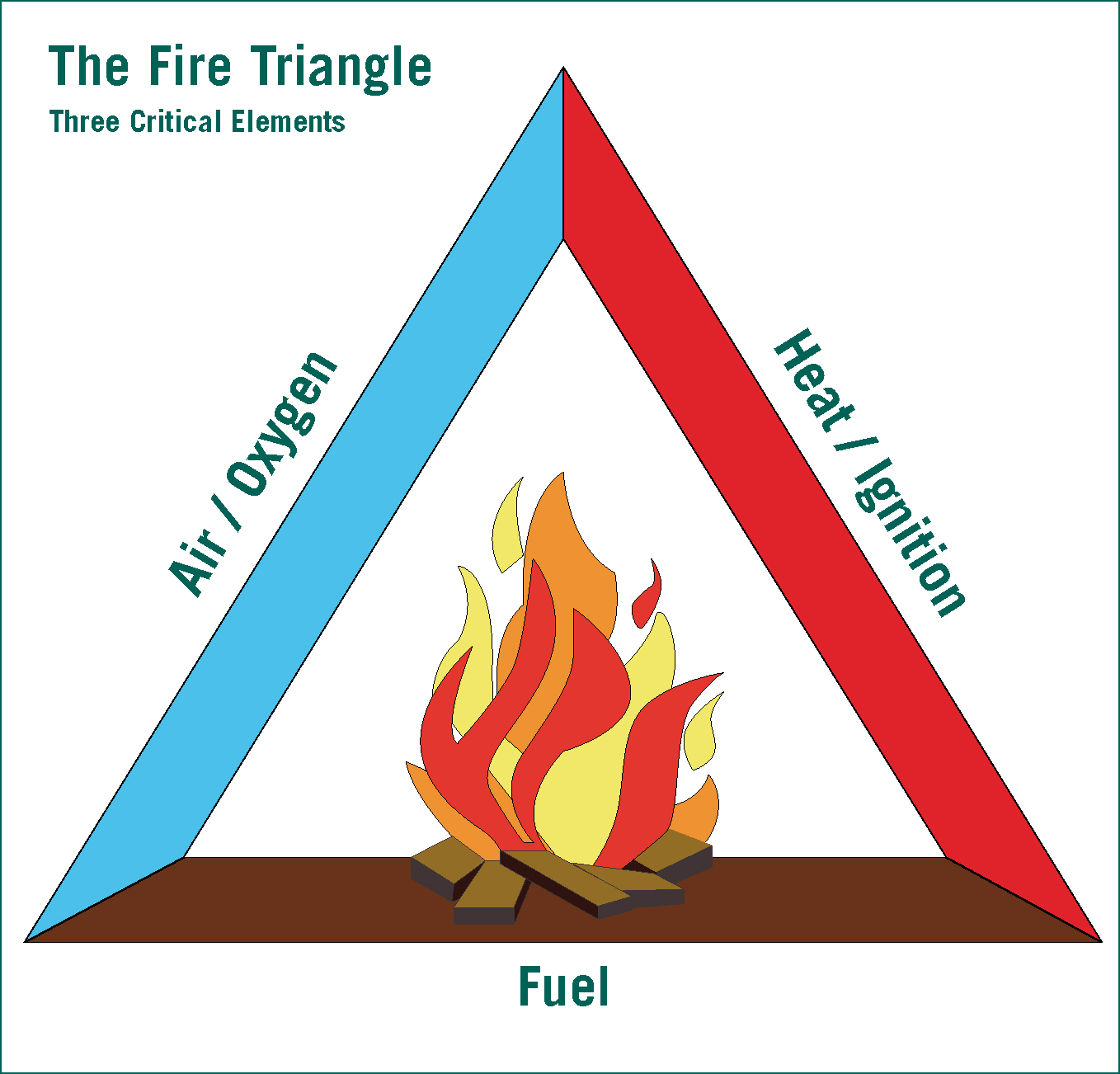

Understanding the ‘fire triangle’ is the most basic concept in fire prevention and control. In order for any fire to occur, three critical elements must be present (Figure 3):

When all of these three elements come together, combustion is the result. However, by removing one of these elements from contact with the other two, the threat of fire can be minimised.

In general practice situations personnel are usually safe as the three elements are kept apart. In the operating theatre, however, factors come into play that increase the risk of these three elements coming into intimate contact. Such factors include:

The theatre team must be aware that all of these elements, fuel, ignition sources and oxygen, are present in every operating theatre during every procedure, therefore every precaution must be taken to ensure they are kept apart. This may be achieved in part by:

Fire precautions

The handling of a fire extinguisher needs regular training as serious injury can result from misuse. Advice from the fire brigade or fire safety company should be sought with regards to which type of fire extinguisher is appropriate, based on the types of materials used in the area. Use of an inappropriate extinguisher could result in further damage. All staff members should be familiar with the location and operation of fire alarms, and evacuation routes (Figure 4) and procedures should be standardised across the team and fire drills held regularly.

Surgical lasers

Laser is the acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. Increasing knowledge and availability has made it more practical for veterinary surgeons to own such equipment hence lasers are more frequently found within veterinary operating theatres. It is imperative that all personnel who work in a practice where lasers are used are trained in laser hazards and safety as the use of lasers in a clinical setting can present significant hazards to the operator and nearby personnel (Berger and Eeg, 2012). Such hazards include:

Surgical smoke plume

Veterinary professionals are likely to have seen and smelled surgical smoke during procedures, but have they ever taken a moment to think about what this smoke is actually made of and if it could harm their health?

Surgical smoke plume is a potentially dangerous by-product generated from the use of lasers, electrosurgical pencils, ultrasonic devices, and other surgical instruments. As these instruments cauterise vessels and destroy tissue, fluid, and blood, they create a gaseous material known as smoke plume (Albrecht and Wasche, 1995). The amount, content, and particulate size of smoke plume can vary depending on the type of thermal tool used. Smoke plume and aerosols contain a wide distribution of particle sizes ranging from 200+ μm to <0.01 μm. The majority of particles in surgical smoke plume measure below 0.3 to 0.5 microns. Albrecht and Wasche (1995) stated this meant that 90% of particles generated during procedures were likely to be inhaled and deposited on the alveolar surface of the lung. This is in congruence with Andreasson et al (2009) whose findings revealed that the size of particles found in surgical smoke plume were small enough to reach alveoli in the lungs and move into the cardiovascular system, potentially causing inflammatory changes in the respiratory tract, nausea, carcinoma and cardiovascular dysfunction.

Laboratory testing from human operating theatres has shown that bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and viruses are present in pyrolised smoke. Researchers have recovered DNA of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and human papilloma virus (HPV) from surgical smoke and were also able to isolate intact viruses. The presence of intact viral DNA suggests that transmission through surgical smoke is a possibility (Garden et al, 2002).

While surgical smoke does contain compounds that are hazardous to health, it is difficult to conclude to what extent individuals are affected by these compounds. Al Sahaf et al (2007) stated that the ethically acceptable solution would be to inform those who are exposed to surgical smoke plume on a daily basis of the potential hazard and to make them aware of the precautions that can be taken. Such precautions include:

Surgical masks

Standard surgical masks provide filtration of particles larger than 5 μm. This is not satisfactory for use with laser surgery because the majority of the particulate matter in surgical smoke contains particles that are considerably smaller. High-efficiency masks are available which can filter particles as small as 0.1 μm, however these must be worn correctly ensuring they fully cover the nose and mouth and do not have any air flow around the perimeter of the mask. Masks must be worn in conjunction with a smoke evacuation system.

Filtered wall suction

Central wall suction systems with inline filtration are available for use during procedures where a minimal amount of smoke is produced. Filters must be checked on a regular basis to ensure they have not become clogged. Wall suction has a significantly lower suction rate when compared with most smoke evacuation units; therefore wall suction is not suited to many situations.

Smoke evacuation units

Smoke evacuation units are generally considered the most effective protection against the hazards of smoke-plume in the operating theatre. Portable systems are available, however, many newer human operating theatres are now installed with a central smoke evacuation system that is connected to several operating suites.

Anaesthetic vapours

Effective scavenging of waste anaesthetic gases, in particular the volatile agents and nitrous oxide, is extremely important as short-term exposure to such gases can affect a person's motor skills, reflexes and alertness, and over time may play a part in a range of health problems including renal, hepatic and neural disease (Saunders, 2004). There are three main methods of controlling the level of exposure of staff to waste anaesthetic gases:

Other hazards in the operating room

Electrical shocks

Electric shocks are usually the result of faulty equipment. Equipment should be regularly inspected for faults. Any faulty equipment should be immediately removed from use and sent to an appropriate engineer for repair. It should be positioned as far away from the anaesthetic gases as possible. Static electricity may be minimised by wearing surgical attire made of an antistatic material such as cotton. The covering of theatre personnel's hair and draping of animal hair will also prevent static build up.

Cleaning agents

Manufacturer instructions should be read carefully and appropriate personal protective equipment should be worn. Products used in the operating theatre should be carefully checked to ensure they are not conducive to fire or explosion.

Head injuries

As operating room lights are adjustable, they may be located in a position that could cause a head injury. Theatre lights should be kept up and out of the way until needed. Once surgery is finished, the light can be moved back up, out of the way.

Slips/trips/falls

The walking surface of the operating room is often contaminated with fluids making it slippery. The wearing of slip resistant foot wear is therefore advised.

Conclusion

The responsibility for making the operating theatre safer extends beyond concern for wellbeing of the patient to all personnel who together form the surgical team. The approaches highlighted in this article are practical and simple to apply. The key to success is to apply the principles and practices in an integrated and consistent manner, providing daily attention to detail and, above all, with support and commitment provided from all members of the surgical team.