By the time most puppies reach adulthood, they will have increased their birth weight by 40 to 50 times (Case et al, 2010). However, as there is a great variation in dog size, from tiny Chihuahuas at around 2 kg to Irish Wolfhounds at around 70 kg bodyweight, growth periods vary. Small breed dogs generally reach adult body size at between 9 and 12 months of age, and large and giant breeds not until they are 18–24 months old (Case et al, 2010); and there are also variations between male and female growth rates.

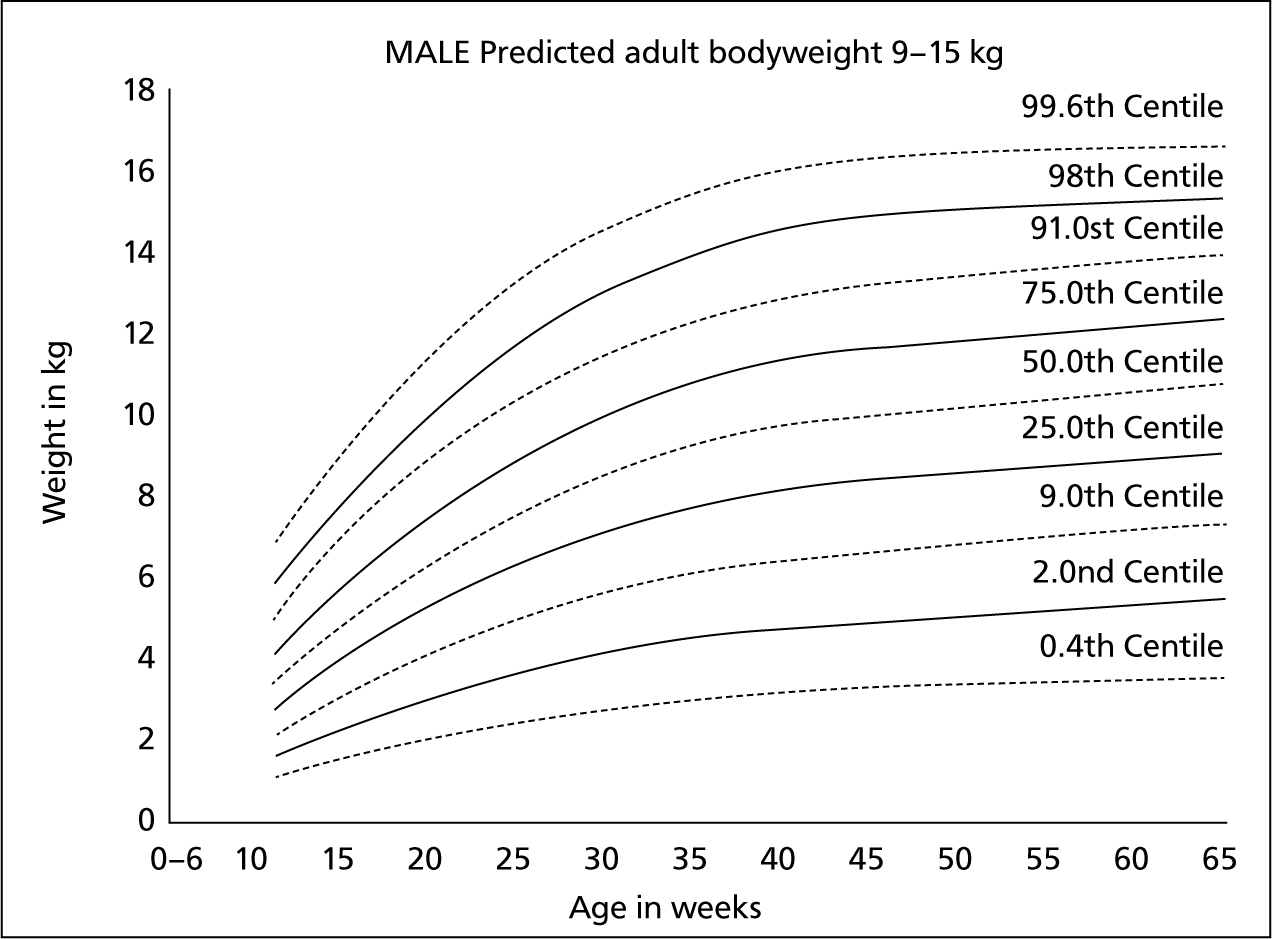

It can be tricky to work out whether a puppy is growing at the correct rate, but an excellent resource to help monitor ideal growth rates are the gender and size specific evidencebased Puppy Growth Charts, which have been developed by the Waltham Centre for Pet Nutrition (WCPN) and can be downloaded from: https://www.waltham.com/waltham-puppy-growth-chart-resources.shtml (Figure 1).

The veterinary team plays a vital role in correcting malnutrition during the growth phase, plotting fortnightly growth on the chart and recommending adjustments either to feeding quantities or indeed a complete change of diet if growth is not ideal. This should be seen as an ideal ongoing opportunity to educate owners on all aspects of pet care and bond clients to the practice.

The growth period can be broken into three stages — pre-weaning, weaning and post-weaning.

Pre-weaning

Puppies are helpless at birth, unable to stand, hear or see, and totally dependent on their mother for the first few weeks of life. During the pre-weaning stage, the dam will ideally provide all the nutrients required via her milk, unless she is unable to for any reason, such as disease, death or low milk yield. Unfortunately, this pre-weaning stage carries the highest mortality rate at around 20% (Chastant-Maillard et al, 2012; Mila et al, 2014a,b, 2015). One important contributing factor to this — along with maternal behaviour and the knowledge and experience of the breeder — is the quality of the mother's diet during the last trimester of pregnancy.

With very few antibodies (only around 10–20%) crossing the placenta (Case et al, 2010), puppies rely on the high quality, and adequate quantity of colostrum to support healthy development. This will provide passive immunity against some infectious diseases during the first 4 months of life. Colostrum is also important for the provision of other bioactive factors (Chastant-Maillard et al, 2017), such as lysozyme, which prevents the growth of certain types of bacteria in the digestive tract, and bile salt-activated lipase, which aids digestion of fat.

A study of 294 puppies by Toulouse Vet School found that low birth weight dramatically increased the risk of death in the first 2 days of life and, in total, almost 50% of neonatal deaths occurred before 1 week of age. Two main factors were found to affect birth weight: size of the breed and size of the litter; and for accuracy, due to the variations in dog sizes, low birth weight was defined independently for each breed size. Mila et al (2014) found that neonatal mortality was directly correlated to the quality of passive immune transfer, meaning that the health of the dam's immune system is key to providing high quality colostrum, and also found that oral supplementation with hyperimmunised canine plasma had no impact on decreasing mortality rates. However, a more recent study (Mila et al, 2017) found that puppies supplemented with hyperimmune egg powder showed increased growth, and a lower risk of acquiring canine parvovirus infection. Mila et al (2014) recommended that close attention should be paid not only to the quantity of natural canine maternal colostrum produced by the dam, but also that puppies begin suckling in the first 4 hours of life. This is because digestive absorption of maternal antibodies becomes progressively more difficult as time passes, and after 12–16 hours, the digestive barrier will be fully closed and transfer of maternal antibodies no longer possible (Chastant et al, 2012).

Also vital during growth is the omega 3 essential fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is vital for neurological and retinal function (Case et al, 2010). Indeed, a study of 48 dogs by Zicker et al (2012) showed improvements in cognitive, memory, psychomotor, immunologic, and retinal functions in growing dogs supplemented with DHA from fish oil. Therefore it is recommended that high quality growth diets should be used that include DHA from fish oil, as these are a better choice for puppies' health.

During the first few weeks, puppies and kittens require very high fat, high protein milk. Table 1 shows the differences in milk composition between species, and illustrates why it is inappropriate to feed cow's milk if hand-rearing a puppy, as the levels of all nutrients in cow's milk are insufficient to fulfil the needs of puppies. While the immune system is still developing, a number of studies have shown that supplementing with antioxidants, specifically with lutein, vitamin A and E and betacarotene, may help boost the immune response to vaccination during the first few months of life (Kim et al, 2000; Koelsch and Smith, 2001; Khoo et al, 2005).

| Dog | Cow | |

|---|---|---|

| Lactose (g/litre) | 33 | 47 |

| Protein (g/litre) | 75 | 33 |

| Fat (g/litre) | 95 | 36 |

| Energy (kcal/litre) | 1460 | 640 |

| Calcium (g/litre) | 2.4 | 1.2 |

| Phosphorus (g/litre) | 1.8 | 0.9 |

It should be noted that two other key nutrients for consideration during growth are calcium and phosphorus, which should be present at optimal levels, as recommended by the European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF) 2018. These are 1:1–1.5:1 for large breeds and 1:1–1.8:1 for small and medium breeds. Recommended amounts, according to FEDIAF, are shown in Table 2, and dietary calcium and phosphorus supplements should never be added to a complete balanced diet for dogs (Case et al, 2010). Due to the immaturity of the intestinal wall in young animals, calcium absorption is passive during this phase and therefore unregulated (Case et al, 2010). The consequences of this will be analysed in more detail later.

| Effect of nutrient level on skeletal development | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient | Low | Medium | High | Nutritional recommendation |

| Protein | Decreased growth rate if deficient | Normal growth rate | Normal growth rate | Diet should contain a minimum of 26–28% protein per 100g |

| Energy | Decreased growth rate if deficient | Normal growth rate | Increased growth rate and risk of skeletal disease and the development of obesity | Calorie density of roughly 360–400 kcals per 100 g diet |

| Calcium | Decreased growth rate. Decreased bone mineral content and strength | Increased bone mineral content. Proper conformation. Reduced risk of hypertrophic osteodystrophy (HOD) | Increased bone mineral content and strength. Poor conformation. Increased risk of HOD | 0.8–0.9% of diet Ca:P ratio = 1:1–1.8:1 |

Weaning

At weaning, around 3–4 weeks of age, puppies will still be growing rapidly and need an energy dense, moist diet, as the teeth are still erupting. This should be highly digestible to avoid digestive upsets (Debraekeleer et al, 2010), as diarrhoea is a common problem in weaning puppies (Baralon et al, 2014). It is also prudent to avoid frequent changes of diet during this stage for the same reason. As the immune system is still developing at this stage, the addition of antioxidants is sensible, and it has been shown by Khoo et al (2005) that when added at levels exceeding official recommendations, puppies' response to vaccination was improved, giving them higher titres following standard vaccination protocols. Therefore, the inclusion of high levels of antioxidants within a good quality growth diet are desirable.

Mohan-Gibbons et al (2012) studied rescue dogs with food-guarding behavioural issues and their key finding was that once in their new home, food guarding in most cases ceased to be a problem. Possibly this was because the perceived competition for food at the rescue centre no longer existed. One could recommend, therefore, that ensuring adequate numbers of bowls during weaning may help reduce the development of this common behavioural problem. In addition, practically, it is ideal to feed a weaning diet that is also suitable for the dam to eat, as puppies learn from their mother and a good quality weaning diet will provide all the essential nutrients required by the dam during lactation and weaning. Normally, weaning should be complete by about 6 weeks of age (Figure 2).

Post weaning

Post weaning, the animal will grow most rapidly until it reaches adulthood. As already mentioned, this phase in dogs' growth varies with different breed sizes, but it is the most rapid growth period for all. The need for energy is greater than at any other stage of a dog's life, with the exception of lactation (Case et al, 2010). This growth phase can be broken into two stages: puppy, which is the early phase before reproductive maturity; and junior, which is after sexual maturity has been reached but while the animal is still growing.

Energy requirements for growing puppies were defined by WCPN (Alexander et al, 2012) (Figure 3). This clearly shows the huge increase in energy requirements for growing puppies and makes it clear that the ideal growth diet should be very energy-dense and provided over several meals because of the sheer volume of food an animal may need to consume to fulfil its daily requirements.

Particular care should be taken with large and giant breeds because their gastrointestinal tract is relatively small, at around 2.7% of their overall bodyweight compared with a human's at around 11% and a small dog's at around 7% (Grandjean, 2006). Given the high energy requirements required by puppies, coupled with an immature digestive tract, one could suppose that feeding an energy-dense diet may be beneficial to puppies and potentially reduce the risk of diarrhoea and thereby facilitate better nutrient absorption.

In general, young animals post weaning tend to be very active and curious, so a high calorie diet is useful to facilitate this (Case et al, 2010), but of course, individuals do vary, so it is important to tailor advice to each puppy. Post weaning, but during the remaining growth phase, the diet should remain of high energy density, with high digestibility, and adhere to the latest published FEDIAF guidelines. If a diet too high in energy was fed, the growth rate would be accelerated (and conversely, if too little energy was provided, growth rates would be retarded), but there is no benefit to speeding up the growing process and in the case of large and giant breed dogs, this may be detrimental, or even catastrophic, to their health (Hedhammer et al, 1974). Fresh water should be freely available during all life-stages and ad lib feeding avoided. Ideally, puppies should have their daily ration split over 3–4 meals until the age of around 6 months, and then meals reduced to twice a day.

Note that as the puppy approaches adult weight, growth slows down and there is a shift in energy utilisation from growth towards daily maintenance requirements (MER). The basic calculation for MER is, according to FEDIAF: 110 x bodyweight (BW)0.75 but each dog should be treated as an individual and by performing a nutritional assessment on each puppy, and by taking into account factors such as health, activity levels, body condition score and sexual status, an accurate MER recommendation can be established.

Key nutrients for consideration during all stages of growth

Back in 1991, a study of Great Danes by Nap and Hazewinkel looked at how growth was affected by increasing protein and calcium. They concluded that it was excess calcium that was responsible for orthopaedic growth deformities, not increased levels of protein. The levels and ratio of calcium (Ca) to phosphorus (P) are a vital consideration during growth and should be present at optimal levels, remain in the correct ratios, as previously stated (noting that levels in larger dogs are lower but in a similar ratio). Ca and P should not be over-supplemented, as defined by FEDIAF.

Other potential complications of over-supplementation of Ca is hypercalcaemia and hypophosphataemia (Case et al, 2010) leading to calcium deposits in the kidneys, causing chronic renal failure and serious effects on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, cardiac function and possibly neurological effects (Gardbaum, 2013). Hypercalcitoninism was also shown by Stephens et al (1985) to occur in dogs fed excess Ca during growth, which resulted in slowing of articular cartilage formation and the possibility of eventual detachment of that cartilage, as seen in osteochondrosis. Unfortunately, supplementing calcium, by adding bone meal to the diet, is still commonly recommended by some breeders today (Case et al, 2010). It should be stressed that dietary calcium and phosphorus supplements should never be added to a complete balanced diet for dogs, as stated earlier (Case et al, 2010).

Finally, copper and zinc, two minerals which work in synergy, are both important considerations during growth (Booles et al, 1991), with copper being vital for osteoblast activity during skeletal growth and to absorb and transport iron, amongst other things (Case et al, 2010). Zinc is important for protein synthesis.

Protein requirements are higher in growth than in adulthood because of muscle building in addition to normal maintenance needs. Protein quality varies widely and the biological value is generally measured by assessing the amino acid profile and the digestibility of the protein source (Hoffman and Falvo, 2005). Animal proteins usually provide all the essential amino acids, but the addition of certain vegetable protein sources, for example wheat gluten, can improve digestibility (Nery et al, 2010).

Consequences of inappropriate feeding

A recent publication highlights the pitfalls of inappropriate nutrition during growth, describing the case of a 6-month-old Giant Schnauzer that presented with intermittent lameness and pain (Tal et al, 2018). The owner had been feeding a complex homemade diet based on an internet-sourced recipe since acquiring the puppy at 2 months of age. Analysis of the diet showed many deficiencies and excesses leading to a diagnosis of nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism and rickets. Changing the diet to one formulated for large puppy growth corrected the problem to some extent, but the dog was left with a permanent hunched posture and 1 year later tired easily during exercise. This highlights the importance of correct nutrition during growth, particularly for large breeds.

Inappropriate feeding during growth can lead to catastrophic skeletal abnormalities, particularly for large and giant breed dogs. First, feeding a diet too high in energy can cause accelerated growth. The Hedhammer (1974) study showed that giant breed puppies fed ad libitum a high energy food displayed a multitude of skeletal abnormalities, including enlargement of the costochondral junctions and the epiphyseal-metaphyseal regions of the long bones, hyperextension of the carpus and sinking of the forelimbs, all of which resulted in pain and lameness. In later studies, feeding a diet excessively high in energy, and the resultant rapid growth, was found to contribute to canine hip dysplasia (CHD) (Case et al, 2010); and in a 2-year study of 48 growing Labradors, feeding one group ad lib compared with a second group that was fed 25% less of the same diet, Kealy et al (1992) found that those fed with fewer calories grew more slowly, had better joint formation, and the incidence of subsequent CHD and osteoarthritis was reduced.

The importance of maintaining an ideal bodyweight

Finally, maintaining an ideal bodyweight right from the start is vitally important for long-term health. With obesity on the rise and being characterised by an expansion of white adipose tissue mass, understanding the way that adipocytes (cells which store fat) react to excessive energy intake is important; in puppies, they increase in number and never go away. In adult dogs they expand in size as a result of excessive energy intake, therefore overweight puppies with higher numbers of adipocytes are much more prone to weight gain and much harder to manage in the long term (Smith et al, 2006). Kealy et al (2002) also showed that 25% calorie restriction to keep dogs lean (BCS 4-5/9) throughout their lives significantly increased lifespan and the onset of age-associated diseases, compared with the control group.

Conclusion

To summarise, growth dramatically affects the nutritional requirements of puppies. If the adult animals are to be of optimal size, form and health, it is imperative that close attention is paid to nutrition from the outset. The growth periods are fast and dynamic with certain specific nutrients essential for the correct formation of musculature, organs, the skeleton and various functions, including vision and brain development. Inadequate or over-nutrition during growth can have catastrophic consequences.