References

How to tube feed

Abstract

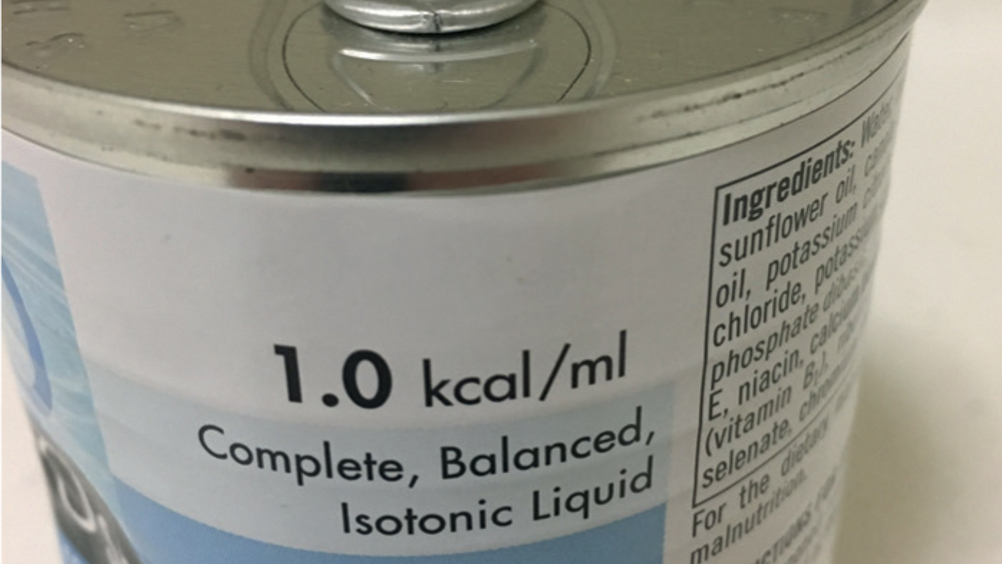

There are many different enteral feeding tubes available for use in veterinary practice to support the nutritional management of a wide variety of patients. This article aims to provide practical advice and guidance with regards to all stages of tube feed administration to ensure it is done safely and the tube is of maximum benefit to the patient and its recovery from illness or injury.

Freeman et al (2011), in the WSAVA nutrition guidelines, described nutrition as the fifth vital sign because adequate nutrition is vital to the healing, health and wellbeing of all animals. There are many indications for enteral feeding of veterinary patients due to many injuries and diseases resulting in a patient being unwilling or unable to ingest adequate calories to maintain health. Examples include mechanical or physical problems such as maxillofacial trauma following road traffic collisions, primary gastrointestinal problems affecting nutrient absorption, or anorexia as a result of metabolic derangements (Ross, 2016). Smith (2019) also highlighted the fact that many patients fail to eat enough food towards the end of their life for various reasons, including patients with conditions such as chronic kidney disease. Whatever the underlying reason for the malnourishment, feeding tubes are an excellent intervention to help support such patients, and it is vital that all veterinary professionals are comfortable with their use to ensure maximum patient benefits.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.