Emergency anaesthesia can be very challenging for the veterinary team. Patients presenting with acute blood loss cause concern regarding cardiovascular and respiratory function, and the ability to perfuse tissue appropriately. An anaesthesia protocol and use of checklists will help to minimise some of these potential complications, while also ensuring the team is well prepared for the unexpected.

Shock is a syndrome which requires careful assessment and rapid treatment. Shock occurs as a result of inadequate cellular energy production or the inability of the body to supply cells and tissues with oxygen and nutrients, and remove waste products.

Shock can be categorised as hypovolaemic, cardiogenic, distributive and/or obstructive. Hypovolaemic shock is one of the most common categories of shock seen in veterinary practice (Pachtinger, 2014).

In hypovolaemic shock, perfusion is impaired as a result of an ineffective circulating blood volume. This hypovolaemia can be relative or absolute.

In relative hypovolaemia, the fluid from the circulatory system does not leave the body. This means that the blood volume is normal but the patient is hypovolaemic as a result of widespread vasodilation. This may be owing to various factors such as disease or anaesthesia.

In absolute hypovolaemia, there is a decreased volume of fluid (blood) within the circulatory system. This may be owing to:

This article will focus on absolute hypovolaemia resulting from acute blood loss.

Patients will often present to the veterinary practice in a hypovolaemic state secondary to haemorrhage, and are at an increased anaesthetic risk owing to multiple changes and/or injuries: these patients are often tachycardic, hypotensive with a reduced cardiac output because of a loss of circulating blood volume. When patients experience blood loss of more than 10% of their blood volume, this will result in hypoperfusion (Table 1) (Muir and Hubbell, 2012). If left untreated, this will lead to metabolic acidosis, hypovolaemic shock and increased morbidity and mortality.

| Normal blood volume | Normal plasma volume | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dog | 80–90 ml/kg | Dog | 36–57 ml/kg |

| Cat | 60–70 ml/kg | Cat | 35–53 ml/kg |

The majority of trauma patients suffer injury-induced haemorrhage, leading to hypovolaemic shock (Driessen and Brainard, 2006). If left untreated, hypovolaemia will lead to irreversible hypoxic tissue injury, circulatory collapse, and multiple organ failure. Even with immediate intensive care treatment, many trauma victims, animals and humans alike, either die within the first 48 hours of hospital arrival (Heckbert et al, 1998), or die later from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) leading to multiple organ dysfunctions (MODS) days to weeks after initial admission (Rudloff and Kirby, 1994).

While all patients should be stabilised as much as is practically possible prior to induction of anaesthesia and correction of hypovolaemia is preferable to ensure perfusion is restored, 100% stabilisation is not always achievable and will not be possible until surgical intervention (e.g. haemoabdomen owing to ruptured splenic mass) is performed.

At present, peri-anaesthetic mortality for healthy dogs and cats is approximately 1 in 2000 (Posner, 2014). The American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) have developed a scale to rate a patient's physical status from 1 to 5 (Table 2). Unfortunately, the morbidity and mortality associated with anaesthesia in critically ill patients is significantly higher and associated with increased odds of anaesthetic death (Bille et al, 2012). This may be in part owing to the selection and use of anaesthetic agents.

| ASA scale | Physical description | Veterinary patient examples |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal patient with no disease | Healthy patient for ovariohysterectomy or castration |

| 2 | Patient with mild systemic disease that does not limit normal function | Controlled diabetes mellitus, mild cardiac valve insufficiency |

| 3 | Patient with severe systemic disease that limits normal function | Uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, symptomatic cardiac disease |

| 4 | Patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Sepsis, organ failure, heart failure |

| 5 | Patient that is moribund and not expected to live 24 hours without surgery | Shock, multiple-organ failure, severe trauma |

| E | Emergency patient | Gastric dilatation-volvulus, respiratory distress |

Previous studies have demonstrated that the dose of an inhalant agent required to maintain anaesthesia is reduced in the hypovolaemic dog (Eger et al, 1965; Mattson et al, 2006). A large-scale, multicentre study of nearly 80 000 general anaesthetic and sedative procedures in cats (Brodbelt et al, 2007) showed a strong association between ASA classification and anaesthetic-related death. Increasing ASA status by one grade (e.g. ASA I/II to ASA III) was associated with a four-fold increase in the odds of death in this population. The hypovolaemic patient is likely to fall between grades 4 and E, depending on the severity of blood loss and/or the time taken to arrive at the veterinary practice.

It should also be noted that while external wounds are often easily identified by the veterinary team on initial presentation, patients presented in a hypovolaemic state have often suffered trauma and additional injuries that are ‘hidden’ on initial presentation, such as a pneumothorax, which will have a significant impact of the risks associated with anaesthesia. In an article looking at the assessment and management of the severely polytraumatised small animal patient, it has been documented that most deaths were caused by intrathoracic, intra-abdominal and central nervous system injury (Dennis, 2006), and these will obviously have an impact on ASA status and, subsequently, anaesthesia risk.

Hypovolaemia affects the volume of fluid in the intravascular space; because intravascular fluid makes up a small proportion of overall body water (1/15th of total body water), any loss can have a profound effect. Patients will show varying degrees of clinical signs, depending on the severity at presentation. These include:

These clinical signs occur because of the body's physiological response to the reduction in circulating volume when losses exceed gains. Fluid will start to move from the interstitium (<1 hour) into the intravascular space, and splenic contraction will occur to release red blood cells from the spleen. The patient will experience a release of catecholamine to increase the heart rate and there will be activation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) to help the body hold onto fluid (sodium and water). The RAAS is a signalling pathway responsible for regulating the body's blood pressure. If the hypovolaemia is not addressed appropriately, patients will have inadequate perfusion of the peripheral tissues causing a progression to hypovolaemic shock.

Hypovolaemic shock consists of two phases:

It is worth noting that changes in packed cell volume (PCV) will be slow if hypovolaemia results from blood loss owing to splenic contraction.

When hypovolaemia is a result of blood loss, emergency surgical intervention and anaesthesia may be necessary to locate and control internal haemorrhage caused by post-traumatic injury. In these patients, intravascular volume losses exceed gains, resulting in a fall of circulating blood volume. This will cause a reduction in ventricular preload producing a reduced and variable cardiac output (Clutton, 2014).

Anaesthesia in this patient group should aim to:

In absolute hypovolaemia, the correct administration of intravenous fluid therapy is required to correct actual losses and maintain ventricular filling pressures, cardiac output and perfusion status. In otherwise healthy dogs and cats, intraoperative fluid therapy usually does not need to exceed 5 ml/kg/hour (Muir, 2012). When blood loss occurs during a surgical procedure, it is easier to estimate losses through calculating the number of swabs saturated with blood and measuring volume of blood in the suction bottles (remembering to subtract any flush used) (Figure 1). In the patient that is already hypovolaemic owing to acute blood loss when presented to the practice, blood loss can be more challenging to calculate and a decision will be made based on clinical signs and blood analysis. It has been reported that seemingly small volumes of blood loss may not be tolerated in sick debilitated or traumatised patients (Moon-Massat, 2014). Volume resuscitation of hypovolaemic patients should aim to achieve a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 70 mmHg (but not above), as this will improve perfusion but minimises the risk of dislodging any clots that have formed (Figure 2).

It is important that accurate monitoring is used to assess gains from infused volumes against losses from haemorrhage and urine. Central venous pressure (CVP) has always been the preferred indicator of blood volume, but is normally only used in the referral and university settings. A newer method is available called the plethysmographic variable index (PVI) (Figure 3), which measures dynamic changes in perfusion index (PI) during one or more complete respiratory cycles, and is considered a breakthrough measurement that can help non-invasively and continuously assess fluid status of patients. In human studies, PVI has been shown to help clinicians predict fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients under general anaesthesia, defined as a significant increase in cardiac output after fluid administration (Masimo, 2011).

A successful anaesthetic outcome in any patient group should focus on excellent patient care and management throughout the entire anaesthetic procedure, and try to minimise the impact that anaesthesia has on the major body systems. Unfortunately, there is not one protocol to meet the needs of every patient and it is up to the veterinary surgeon to design an appropriate protocol to meet the individual patient's needs.

Pre-anaesthetic assessment and preparation

The pre-anaesthetic period is extremely important to ensure successful anaesthesia. This section will cover what it should include.

Patient assessment and stabilisation

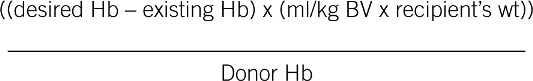

The patient assessment includes a thorough history taking, physical examination and diagnostic tests to help determine the patient's physical status prior to anaesthesia (see Table 1). While all patients should be stabilised as much as is practically possible prior to induction of anaesthesia, 100% stabilisation is not always achievable with the hypovolaemic patient as previously discussed. Fluid resuscitation to correct volume deficits in the hypovolaemic patient will be necessary, although the best choice of fluids is controversial. Ideally if a patient has lost >20% of their total blood volume (>10% in debilitated animals) (Egger, 2014), blood lost should be replaced with blood products such as whole blood or packed red blood cell (Box 1). If blood lost is <20% in a healthy animal (<10% in a depilated animal), they can be treated with administration of a crystalloid such as Hartmann's solution at three times the volume lost or a colloid at equal volumes lost. Some people avoid colloids owing to their documented negative effects on coagulation. Others feel they should be considered in patients with a total protein of <4.5 g/dl (Machon, 2009). Volulyte® (Fresenius Kabi) is licensed for giving during haemorrhage.

Where rapid fluid resuscitation is required, or where huge volumes of crystalloids would put the patient at risk of over-infusion or haemodilution (decrease in the proportion of red blood cells relative to the plasma), hypertonic saline (7.5%) may be more appropriate. It is administered at 4 ml/kg over 10 minutes prior to crystalloid administration.

Oxygen administration will help address hypoxia while either packed red blood cells or whole blood are administered to replace lost circulating volume and oxygen-carrying capacity. Critical haemoglobin concentrations (i.e. the value below which oxygen delivery is unable to meet tissue oxygen demand) may be as low as 3–5 g/dl (i.e. a PCV of 9–15%) (Machon, 2009) and PCV greater than 15–20% is ideal prior to anaesthesia to ensure that adequate oxygen delivery can be achieved.

Preoperative fasting should always be performed but when presented with an emergency patient, it is better to presume they have a full stomach and take necessary precautions associated with the patient regurgitating, especially during intubation. Problems such as hypotension, hypovolaemia, hypothermia and sympathetic nervous system activation also slow gastric emptying, and care should be taken to mini-mise the risks of vomiting or regurgitation with subsequent aspiration in patients presenting with these problems (Machon, 2009).

Development of an anaesthesia and analgesia plan

Unfortunately, most anaesthetic agents will have an effect on the patient's heart rate, stroke volume, cardiac contractility, systemic vascular resistance and therefore cardiac output and blood pressure. These effects combined with a patient who is already having issues in maintaining adequate delivery of oxygen to tissues can present many challenges to the anaesthesia team.

During anaesthesia, the aim should be to select drug combinations that have a minimal effect on the patient's cardiac output, to keep adequate (although not always normal) tissue perfusion and oxygenation. Drug doses may need to be reduced in these patients owing to a reduction in volume distribution (Clutton, 2014). Ultimately doses that achieve a suitable depth of anaesthesia with minimal ventilator and cardiovascular depression should be administered.

Drugs should be selected on their ability to maintain systemic vascular resistance. Many drugs such as acepromazine cause vasodilation and should be avoided in the hypovolaemic patient, as these can cause a relative hypotension (see Table 3). A well thought out analgesia plan will enable inhaled anaesthetic agents to be significantly reduced, resulting in less reduction of SVR.

| Example of drugs that cause a reduction in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) | Example of drugs that do not change systemic vascular resistance (SVR) |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Preparation of anaesthetic drugs and equipment

The veterinary nurse who invests time in ensuring that all anaesthetic machines, breathing circuits, an-aesthetic monitors and ancillary equipment are available and functioning correctly will be rewarded in the long run. Being prepared has a significant impact in reducing emergencies during the anaesthesia and surgical period. The implementation of safety checklists has been paramount in reducing anaesthetic and surgical complications in human medicine, and their implementation is gaining recognition in the veterinary setting with the help of organisations such as the Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists.

Premedication

A well thought out premedication plan has a huge number of benefits. These include:

Hypovolaemic patients may have a delayed absorption of drugs administered subcutaneously, so intramuscular or intravenous administration via a peripheral catheter may be better as this allows drugs to be titrated until the desired response is seen. Drug combinations such as opioids and benzodiazepines cause minimal negative effect to the cardiovascular system so can be very useful in cases where cardiovascular compromise is being experienced.

Induction

While there are pros and cons to all induction agents, the veterinary team is often restricted by what they have available to them in their individual settings. Propofol is best avoided in hypovolaemic patients; it can cause moderate hypotension because of reductions in cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance, which can become severe in hypovolaemic patients (Kastner, 2014). In a study comparing the cardiopulmonary effects of anaesthetic induction with isoflurane, ketamine-diazepam or propofol diazepam in hypovolaemic dogs, there was evidence that a ketamine-diazepam induction combination maintained significantly higher blood pressures after induction (Fayyaz et al, 2009). Ketamine can however cause decompensation in the very critical patient as it stimulates their already hardworking cardiovascular system as a result of stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. This causes an increase in heart rate, myocardial work and oxygen consumption.

Psatha et al (2011) looked at the clinical efficacy and cardiorespiratory effects of alfaxalone, or diazepam/fentanyl for induction of anaesthesia in dogs that are a poor anaesthetic risk. The study concluded that induction of anaesthesia with alfaxalone resulted in similar cardiorespiratory effects when compared with the fentanyl-diazepam-propofol combination, and that alfaxalone is a clinically acceptable induction agent in sick dogs (Psatha et al, 2011).

Etomidate is a good choice when cardiovascular compromise is a concern, as it causes no change in heart rate, vascular tone, stroke volume or contractility (Sager, 2012). However, it has gone out of favour as etomidate inhibits 11-B-hydroxylase, which is an enzyme important in adrenal steroid production. A single-induction dose blocks the normal stress-induced increase in adrenal cortisol production for 4–8 hours, and up to 24 hours in elderly and debilitated patients, and its use has declined in recent years because of a perceived potential morbidity (Lupton and Pratt, 2008).

The aim should be to ensure that the induction phase is as stress-free as possible with gentle and calm handling of patients to avoid catecholamine release and arrhythmias. All patients undergoing anaesthesia should have an intravenous catheter placed to allow for induction agents to be titrated to effect. Patients should be pre-oxygenated for a few minutes prior to induction to allow time for monitoring equipment to be attached and to help to prevent hypoxaemia during the induction and intubation phase. Hypoxaemia is extremely significant in patients who have lost a large blood volume and, therefore, oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Induction should be fast and smooth in emergency patients who are at a greater risk of regurgitation and aspiration owing to a lack of starving. The patient's head should be held up until intubation has been achieved, and the endotracheal tube is secured and cuff inflated, before placing the patient's head down. Masked inductions should be avoided as they take too long to gain a secure airway.

Maintenance

Inhalants such as sevoflurane and isoflurane both cause dose-dependant cardiovascular depression; the use of multimodal anaesthesia and analgesia will enable the volatile agent to be reduced. Concurrent administration of opioids, either via a constant rate infusion (CRI) or intermittent slow bolus administration and/or local anaesthetic techniques (where appropriate), is particularly useful in reducing volatile agent requirements and reducing their negative effects.

During anaesthesia maintenance, it is important that the patient is continuously monitored by someone who has an understanding of basic physiology and of the technology being used. The anaesthetist/nurse should monitor more than one parameter throughout the whole procedure, ensuring findings are documented correctly every 5 minutes. Use of an anaesthetic record is important as they encourage regular monitoring and assessment, and allow earlier recognition of changes in vital organ function.

Initially, the patient's response to acute blood loss is to increase cardiac output by increasing heart rate, systemic vascular resistance, contractility and stroke volume. In addition, they will have an elevated respiratory rate and tidal volume, to try and increase oxygen uptake, and will also increase oxygen extraction within the tissues (Egger, 2014). Once all of these things have occurred, delivery of oxygen to the tissues is reduced despite the body's best efforts, and oxygen content must be increased to prevent the development of shock. Appropriate airway support must be ensured while the patient is intubated and during recovery to support oxygenation and ventilation. Circulatory function should be supported with the delivery of intravenous fluids and aggressive treatment of hypotension. Prevention of intraoperative hypothermia is always important but the effects associated with hypothermia in the hypovolaemic patient can cause a significant increase in postoperative morbidity and mortality. Hypothermia causes CNS depression, bradycardia, hypotension, hypoventilation, and decreases in metabolism, urine output and anaesthetic requirements.

Recovery

Recovery begins as soon as the volatile agent is switched off and forms the last period of anaesthesia. It ends when the patient is fully awake and responsive, which can vary considerably from patient to patient, depending on their pre-anaesthetic status and whether they experienced any complications during surgery.

The recovery period is often overlooked despite it being the time when many complications can arise. The confidential enquiry into perioperative small animal fatalities (CEPSAF) documented that 47% of all anaesthetic-related deaths in dogs, and 61% of those in cats, enrolled in the study took place within the recovery phase, with the majority dying within the initial 3 hours of recovery. Many of these deaths were thought to be a result of respiratory or cardiovascular complications, often occurring when patients were not being observed.

The veterinary team that plans ahead for complications will feel more confident during this phase. The recovery area should be warm, draft-free, well-stocked, and have the availability to perform advanced monitoring and administer oxygen if required. There should be a designated member of staff in charge of recovering patients and these patients should not be left unattended until they are stable enough to be transferred to wards.

A recovery protocol will ensure in-house stand-ardisation, and documentation of findings should alert staff to any gradual changes in patient status. Many patients will require ongoing heat support. The potentially disastrous effects of hypothermia experienced during the maintenance phase of anaesthesia can continue to cause problems for the patient in the recovery phase. In people, postoperative shivering has been shown to increase oxygen consumption by over 800% and may be sufficient to physically disrupt sutured wounds (Machon, 2009). It is important to stop active heat-warming before the patient becomes normothermic, to prevent hyperthermia.

Post-anaesthetic monitoring should be continued at regular intervals and documented to help assess vital organ function. The strength and quality of the pulse, as well as the heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, mucous membrane colour, and CRT, should be monitored every 10–15 minutes. More intensive patients may require additional monitoring such as blood pressure, electrocardiogram (ECG) if cardiac arrhythmias were a concern intraoperatively (e.g. splenectomy), and estimation of arterial oxygen saturation (SPO2) using a pulse oximeter to determine whether oxygen supplementation is required.

These patients will require ongoing intravenous fluid therapy and laboratory tests to monitor PCV and total solids (TS), with the potential need for intermittent blood gas analysis and regular assessment, to ensure no further blood loss is experienced. Intravenous catheters need to be maintained and patients should receive regular pain scoring to assess analgesia requirements. A nutritional assessment should also be performed.

Conclusion

These patients present many challenges for the veterinary team. The routine use of ASA grading systems, anaesthetic checklists and practice protocols will enable the team to work as efficiently as possible in an emergency situation.