As hind gut fermenters, rabbits and other lagomorphs constantly require low-quality roughage and fibre to ensure continued gut motility, because of their highly specialised digestive tract. Many factors can contribute to the development of gastrointestinal stasis, characterised as reduced motility of the digestive tract. This can be caused by incorrect, or lacking, nutrition, but also as a result of stress and some medications used within the practice (Prebble, 2012). As with many herbivores, rabbits themselves must digest a significant quantity of vegetation to meet their nutritional needs, with the caecum and colon being of greater importance than that of canine and feline species (Carabaño et al, 2010). Because of the special nature of their digestive systems, they also have more microbial activity in their digestive tract when compared to other species, to aid digestion of vegetation and roughage.

One major part of rabbit nutrition behaviour is the consumption of a special type of faeces called caecotrophs. These caecotrophs contain vitamins and amino acids produced by microbial activity, and are directly consumed from the anus (Pollock and Irlbeck, 2011). This process allows for a much more efficient digestive system as it enables the absorption of essential compounds that would be lost by other species.

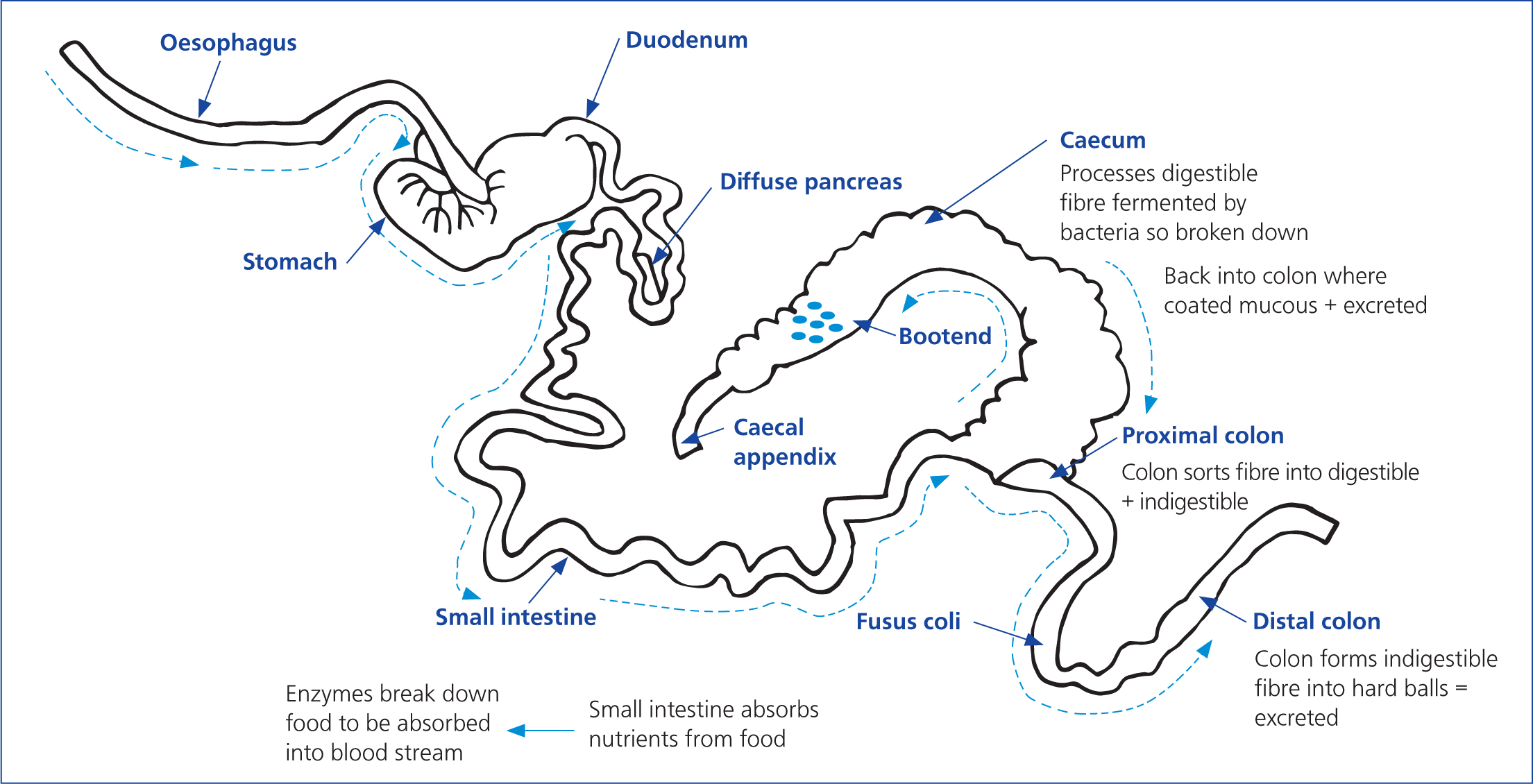

In addition to the importance of the caecum and colon, the stomach is also vital to rabbit digestion. This is always partially filled, as rabbits need to constantly ingest food to ensure continued gut motility. It has a weak muscular layer, and after caecotrophy, another compartment known as the fundic region acts as a storage cavity for caecotrophs (Carabaño et al, 2010). The stomach itself is linked by a small intestine with a coiled caecum (Figure 1), and is important for the secretion of bile digestive enzymes and buffers (Carabaño et al, 2010). Through passive or active transportation throughout the mucosa, the small intestine allows the greater part of digestion to take place (Carabaño et al, 2010). There are many other tissues associated with the gut, and various factors such as pH levels that contribute and assist in digestion; however, it is beyond the scope of this article to go into extensive detail (see Blas and Wiseman, 2010).

Feeding: the ideal diet

As discussed, rabbits require a source of low-quality roughage, as well as a handful of non-selective pellets, and some fruit/vegetables in small amounts. Ideally, they should receive at least 80% of their bodyweight in hay, as well as an adult-sized handful of fresh greens and vegetables (PDSA, 2021a). Bowls are not always required, as rabbits are used to foraging for their food in the wild. Rabbits' teeth grow throughout their lives, and the specific chewing action of eating grass and hay, along with the abrasiveness of the silica in the grass leaf, helps to keep their teeth worn naturally (Bourne, 2009). Muesli style diets should not be fed as they can predispose and excerbate any dental issues (Bourne, 2012). Feeding of a highly calorific diet such as muesli, excessive pellets and low levels of grass and hay can also lead to obesity (Stapleton, 2014).

Fresh water should also be available at all times (PDSA, 2021a). Any changes to their diet should be completed gradually, and the rabbit's weight should be closely monitored. Exercise should be encouraged, and it is important that rabbits have as much space as possible, however, it is important to ensure that rabbits are being feed fruit and vegetables that are safe to eat, and that any outdoor exercise area is securely checked and maintained (PDSA, 2021a). If there is any decrease or reduction in the rabbit's appetite for any reason, then veterinary advice should be sought immediately.

Nutrition in the critical care patient

The rabbit's digestive system is important for ensuring the rabbit obtains the nutrients required, and correct and consistent feeding is essential, however, what action should be taken when things go wrong? Failure to meet the demands of the rabbit digestive system will disrupt the balance of the microflora of the gut (Oglesbee and Lord, 2020), and will result in bloat, or fatal damage to the digestive system itself, through damage to the gastrointestinal mucosal lining. There are several options for providing nutrition in the critical and hospitalised patient, including tube and syringe feeding, and the owner should be encouraged to bring in some of the animal's food from home to encourage them to eat. Both bedding hay and grass hay, and additionally alfalfa, can be kept in the hospital, as well as several different options for syringe feeding (Pollock, 2011) (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Table 1. Foods for the herbivore patient (including brands)

| Species | Feed |

|---|---|

| Herbivore (chinchillas, degu, prairie dog, guinea pig, rabbit) | Syringe/tube feeding Emeraid IC HerbivoreEmeraid sustain herbivoreGround pellet slurryOxbow critical care |

| Solids PelletsHayGreensCarrot topsVegetables with a low calcium content |

Providing any critical care nutrition depends on the disease process and/or the patient's specific requirements. Malnutrition has been associated with many concerns including a higher infection risk, prolonged hospitalisation and increased fatalities; endotoxic shock has been reported as a result of bacterial proliferation and bacterial translocation in anorexic rabbits (Rosen, 2011). Therefore, it is important that when providing critical care nutrition, the chosen diet is provided in sufficient quantities. A full examination must be carried out before starting any nutritional supplementation, and it should be recognised that for any critically ill patient, the stress of being in a hospitalised environment can affect food consumption and metabolism (Hamlin, 2011). Nutritional needs should be calculated using resting energy requirements (RER) as well as consideration for the provision of water, protein, vitamins, minerals, fats and carbohydrates. Micro enteral nutrition, i.e. the provision of very small amounts of water, electrolytes and easily absorbable nutrients directly into the gastrointestinal tract, should be considered (Ackerman, 2019).

Ongoing treatment

Few drugs are licenced for use in rabbits, meaning that many are prescribed under the cascade when treatment is needed. Some medications must be avoided or used with great care as they can affect the microflora within the gut and may result in overgrowth of bacteria such as clostridium, enteric dysbiosis and/or enterotoxaemia (DeCubellis and Graham, 2013). Prokinetics are also often used in conjunction with treatment to help try and increase and encourage gut motility (Mayer, 2015). It is important to converse with the leading clinician regarding the medical treatment plan and its potential implications for the patient.

Implementing critical care nutrition

In terms of critical care nutrition, there are various options. The main ones discussed throughout the literature are syringe feeding and nasogastric tube feeding.

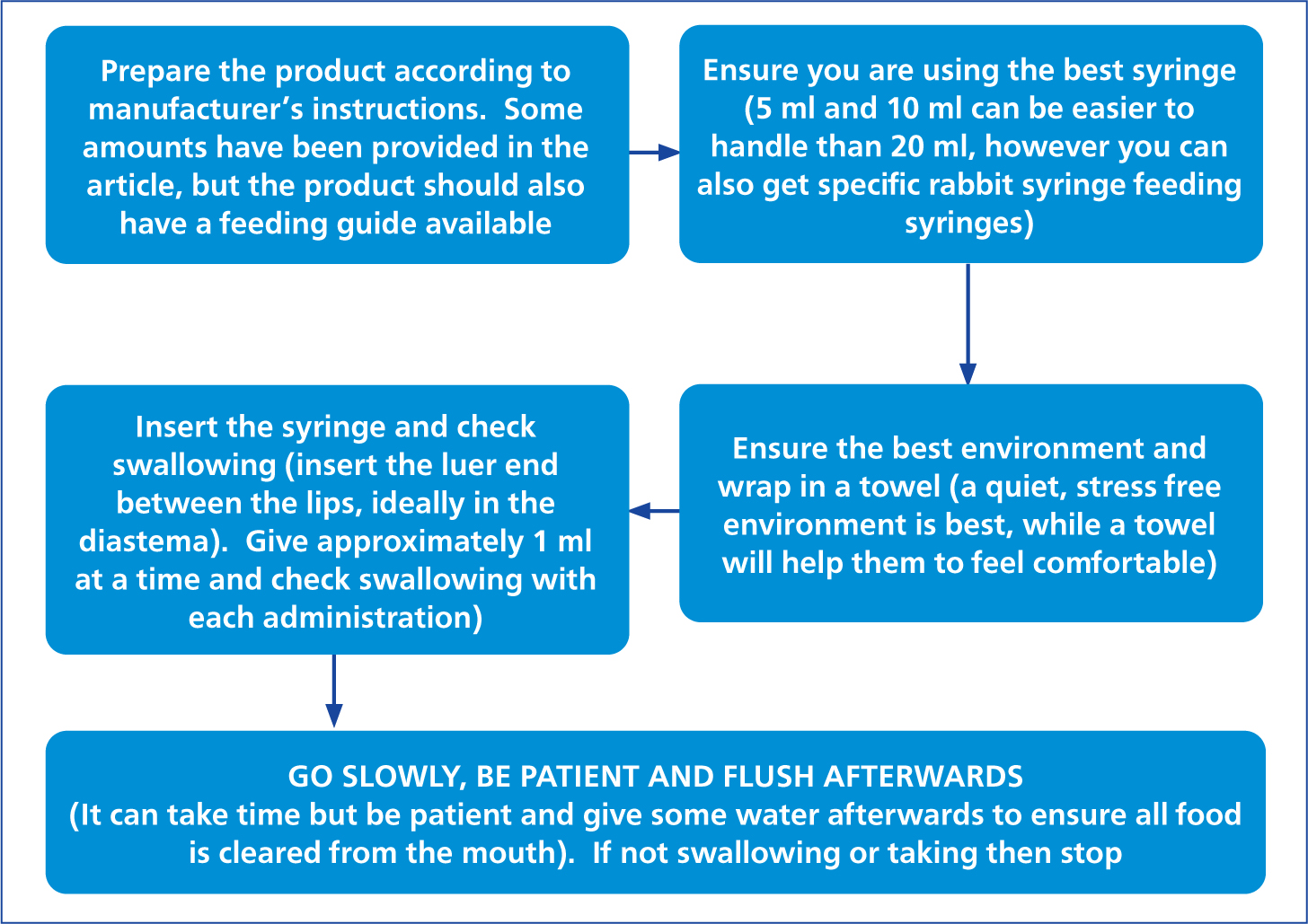

Syringe feeding should only be initiated on veterinary advice and once a blockage in the rabbit's gut has been ruled out. There are a number of species-specific foods available, however, the main ones include those made by Burgess, Oxbow, Lafeber and Supreme. The majority of these are mixed with warm water and the consistency can be altered to suit the individual rabbit's needs. Other foods, such as carrots or fruit puree, can be added to the mix to make it more appetising, and to allow it to pass through the tube more easily if necessary. It should always be ensured that the rabbit is swallowing and taking the food properly during the syringe feeding (RWAF, 2021) (Figures 3 and 4).

Recommended amounts to be fed vary between sources, however, an amount of 8–12 ml/kg of feed should be given (RWAF, 2021). Oxbow critical care advises that for herbivores, the general amount should be 3 tablespoons of dry product or 50 ml mixed product daily per kilogram of bodyweight, however, they do also provide a feeding chart with recommendations according to size. Syringe feeding is a short-term solution, and as soon as the rabbit is eating by itself, then their normal diet should be gradually reintroduced.

It is important to note that Emeraid is a semi-elemental diet, and is very different from some of the other tube feeding diets available. In an elemental diet, the elements have been broken down into small and easy to absorb components. This is beneficial, because critically ill patients do not have the energy required for effective digestion in addition to that required for healing and repair of the body. Therefore, elemental nutrition provides small and simple to absorb components, such as as amino acids, so that patients can still receive the nutrition that they need. This type of nutrition is well tolerated in patients with gastrointestinal problems, particularly malabsorptive states like inflammatory bowel disease, dietary sensitivities, infectious enteropathies, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, neoplastic infiltration of the bowel, or pro ventricular dilation disease in birds (Pollock, 2018). The Emeraid system provides species-specific nutrition, and is designed for the patient recovering from critical illness or suffering from chronic medical conditions. There are many products available, however Emeraid Sustain Herbivore, is a high fibre recovery diet designed for the long-term feeding of debilitated small herbivores (Pollock, 2018).

It is important with any syringe feeding that the correct syringes are used, especially for the Oxbow Critical Care, as adding warm water can make the fibre swell, so it is useful to remember to use the syringes provided with the product.

It is also important to check the hydration status of the rabbit (Burgess, 2021). Ensure fluids are warmed before giving; intravenous (IV) boluses are considered a good choice for both welfare and access. The solution administered should be physiologically balanced.

Generally, in the author's experience, the lateral ear vein is used because of the ease of access, placement, and the volumes that can be administered. Saphenous and cephalic veins may be used, with marginal veins only used when there are no other sites possible (Rosenthal, 2001). A fluid rate of 10–15ml/kg of isotonic crystalloids should be administered, followed by a 5 ml/kg infusion of Hetastarch over 5 to 10 minutes (Lichtenberger, 2008). Blood pressure should be checked, and maintenance rate given once it is over 40 mmHg systolic. Any warming procedures should be done slowly over about 30–60 minutes for both the fluids and the patient through the use of hot water bottles (Lichtenberger, 2008).

Blood work is also extremely important, especially when treating cases such as hypovolaemic shock in the initial phase. Ideally the packed cell volume (PCV), total protein (TP), glucose and blood urea nitrogen should be measured. It is important to note that most biochemical parameters of rabbits can be measured from plasma or serum. Blood also clots easily, especially at room temperature and will do so quickly if not mixed with the correct anticoagulant (Melillo, 2007).

There are various protocols for both cases of dehydration, and gastric stasis. The use of a rehydration formula is extremely important to ensure correct volume of fluid is delivered (Lichtenberger, 2008):

Volume (1) = hydration deficit × body weight (kg) × 100.

Nasogastric tubes

A further method of administering nutrition involves the placement of a nasogastric (NG) tube. In a critically ill patient, or one undergoing surgery, this can be an extremely useful way of delivering nutrition and fluids when other methods are not feasible. In addition to rabbits that are impossible to syringe feed, or are not taking food from a syringe, animals with anorexia for more than 24 hours, jaw trauma, acute trauma, hepatic lipidosis, and those that will undergo oral, pharyngeal, oesophageal, gastric or biliary tract surgery are all candidates for placement of an NG tube (Brown, 2010). As well as being able to eat, drink and swallow around the tube, thus promoting the return of normal feeding, this tube also provides a way to deliver calories and fluids, and thus helps to rehydrate the stomach contents (Brown, 2010). Keto acidosis and hepatic lipidoses can develop in rabbits that have been anorexic (Rosen, 2011; Harcourt-Brown, 2011) and especially in overweight rabbits (Brown, 2010).

Typically, a 5Fr to 8Fr tube is used, however, this can vary depending on the size of the rabbit. The distance from the tip of the nose to the last rib is measured, and a formulation of Oxbow Critical Care Fine Grind or Emeraid Herbivore should be used, as these are hay-based and will pass through these tubes easily. The full method of placement is outside the scope of this article, however, complications can include placement in the trachea, epistaxis, damage to the mucosa, tube blockage, reflux, aspiration and nasal discharge (Brown, 2010). The tube is easily removed with the rabbit awake and can remain in place for weeks or until the rabbit is eating well on its own.

There are many factors that need to be considered when placing a tube, and x-rays should be taken after the placement as tracheal placement is possible and seems to be easily tolerated in very sick rabbits. Considerations include the level of debilitation of the rabbit, the possibility and if surgery is present, and especially the temperament of the rabbit, as tube feeding can be less stressful than syringe feeding in some cases. A full health check should have been conducted before, and any blood work and fluid therapy requirements already calculated and worked out, as this will need to be considered when the feed is being administered and calculated. Local anaesthetic is also recommended as this will help during placement (Paul-Murphy and Pollock, 2011).

In terms of welfare considerations and contraindications, severe trauma to the midface or recent nasal surgery would negate the placement of NG tubes. Relative contraindications could include alkaline ingestion, oesophageal stricture and coagulopathy (Paul-Murphy and Pollock, 2011).

Conclusion

It is clear that there is still a long way to go to ensure the nutritional provision for rabbits in the clinical setting is maintained. Lots of factors need to be considered to ensure a swift recovery from a variety of medical situations. Mitigating these factors, either by stress reduction or the use of medications, is essential to facilitate the patient's health. It is also important to understand the anatomy of the patients in practice, and providing them with the correct nutrition is essential from the offset. Although rabbits are popular in the UK, owner education is needed to improve the welfare of these animals and to encourage understanding of their unique biology.

KEY POINTS

- Providing the correct nutrition is key to helping to maintain a healthy digestive system as well a healthy gut microflora.

- Critical care nutrition in the rabbit patient needs to be tailored to the individual patient, using the correct and most suitable products.

- The correct method of syringe feeding should always be employed to reduce the risk of further complications that could be detrimental to the rabbit's health.

- All aspects of critical care must be looked at including weight and intravenous (IV) fluid provision, as well as the correct and most appropriate choice of feeding tube if this is applicable.

- Any medications should always be given on veterinary advice and syringe feeding should only be initiated once a blockage has been ruled out.