References

Moral distress, compassion fatigue and burn-out in veterinary practice

Abstract

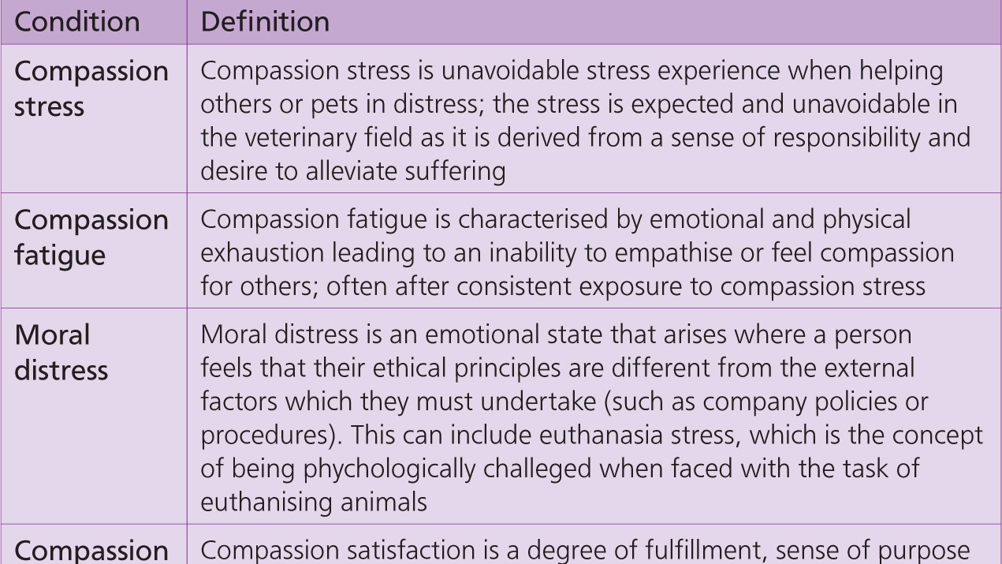

Concerns regarding compassion fatigue and burn-out in veterinary practice are steadily increasing. Burn-out is defined as the state in which a person feels emotionally, physically and mentally exhausted. Work-related stress can have a significant impact on our quality of life and unfortunately lead to burn-out, moral distress and compassion fatigue. As veterinary professionals are exposed to ethical dilemmas and stressful situations daily, it is important that they are aware of the signs of burn-out and how it can be managed.

Veterinary professionals are becoming increasingly concerned about compassion fatigue and burn-out. The incidence of burn-out is on the rise among veterinary professionals, and negatively affects personal and professional wellbeing, and the provision of care to patients. There is evidence that the emotional exhaustion component of burn-out correlates with physical and mental health (Lovell and Lee, 2013). Several studies have shown that emotional exhaustion and mental health illnesses are significantly higher among veterinary surgeons (VS) and registered veterinary nurses (RVNs), with the rate of suicide in the veterinary profession four times the rate of the general public (Halliwell and Hoskin, 2005; Bartram and Baldwin, 2008). In order to source timely help for mental wellbeing, it is helpful to establish what the causes of burn-out and compassion fatigue are to help understand them.

The veterinary environment can be inherently stressful and demanding, as veterinary professionals often deal with euthanasia and end-of-life care, economics, staff shortages, and even bullying in the workplace. Veterinary professionals are known to have perfectionist personality traits that can lead to working long hours, poor sleep patterns and as a consequence, lack of supportive relationships in the work and home environment (Crane et al, 2015; Armitage-Chan et al, 2016). Burn-out is a gradual process but it can sometimes feel unexpected or sudden should the person fail to recognise the signs and symptoms.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.