References

Syringomyelia and Chiari-like malformation

Abstract

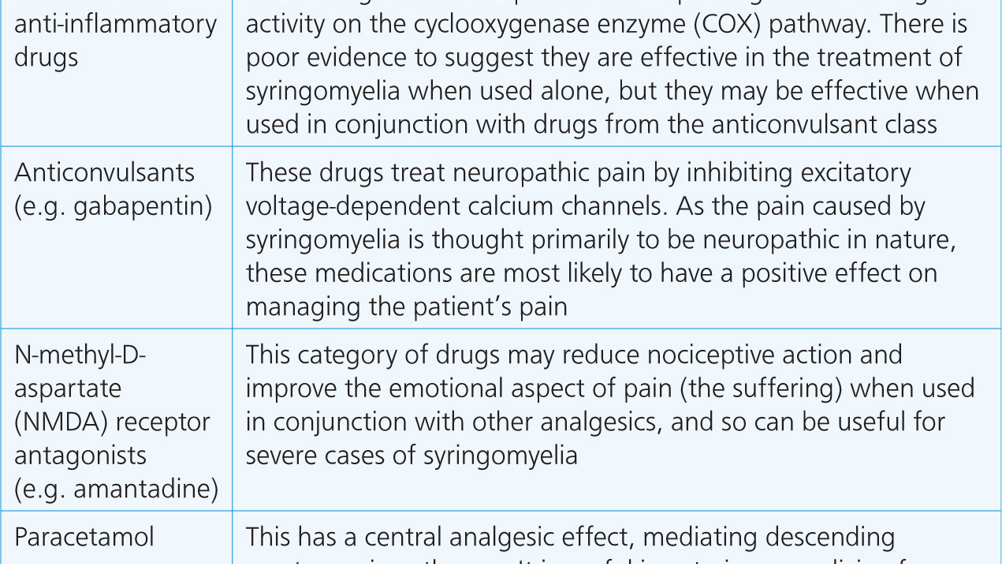

Syringomyelia is a heritable condition caused by fluid-filled cavities in the spinal cord as a result of the abnormal flow of cerebrospinal fluid. This results in a number of debilitating clinical signs, including neck pain (which often manifests as scratching or ‘phantom scratching’, head shy behaviour and vocalisation) and neurological deficits. Management may be conservative or surgical but, in most cases, the condition is progressive, regardless of the treatment option pursued.

Syringomyelia is a debilitating, painful condition that affects both humans and canines, and is particularly prevalent in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS).

Syringomyelia can be defined as the collection of fluid within the cervical, thoracic and, on occasion, the lumbar spine. The collection of this fluid is caused by overcrowding in the cranium, which leads to herniation of the cerebellum through the foramen magnum (the opening at the base of the skull through which the brain and spinal cord are connected) (Hechler and Moore, 2018). This is thought to be primarily caused as a result of an abnormality in the shape of the skull related to brachycephalic syndrome, known as Chiari-like malformation (Hechler and Moore, 2018). Although the CKCS is the breed most often associated with this condition, it can affect many other toy brachycephalic breeds, including the Griffon Bruxellois, Affenpinscher, Chihuahua and Papillon (Wijnrocx et al, 2017).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.