A 10-year-old male domestic shorthair cat was admitted to hospital following a road traffic accident (RTA). On admission the patient was mobile but reluctant to move. He was fairly bright and responsive but was vocalising and was reactive to examination of the left hind limb.

The veterinary nurse (VN) allocated to this case had extensive involvement with patient care in the initial 2 days post RTA. Involvement on the day of surgery included preoperative assessment and preparation, intraoperative anaesthetic monitoring and postoperative recovery and care including pain assessment and management.

History

On admission the cat's vital parameters were determined: heart rate (HR) was 168 beats per minute and respiratory rate (RR) 48 breaths per minute (Table 1). This elevation in RR may have been due to stress, pain or a cough the owner reported. Examination of the left hind limb was poorly tolerated implying trauma. The tail was fractured 12 cm proximal to the tip and there was no movement or sensation distal to this. Both were confirmed by radiography under general anaesthetic (GA). In-house blood analysis revealed mild hypoproteinaemia and anaemia. This was indication for further stabilisation before surgery due to the potential for hypoxia and an alteration in drug potency in the patient.

Table 1. Normal parameters for vital signs in a feline

|

|

Treatment on the day of the RTA included intravenous fluid therapy (IVFT), antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesia. IVFT, NSAIDs, opioid analgesia and antibiotics were continued for 2 days before being discharged and monitored at home. Meloxicam (Metacam®, Boehringer Ingelheim), buprenorphine (Buprecare®, Animalcare) and theophylline (Corvental-D, Elanco Animal Health) were continued at home. The patient was readmitted 6 days later for excisional arthroplasty of the dislocated left hip joint and amputation of the fractured tail.

Case description

Preoperative assessment and hospitalisation

On admission, the last time and doses of medication given at home were confirmed. It was checked that no vomiting or diarrhoea had occurred as this may indicate a reaction to medication. The patient's appetite and thirst were discussed. The owner confirmed starvation from six o'clock the previous evening, advised to reduce the risk of regurgitation under anaesthesia. Informed consent was obtained from the owner after the procedure and risks were understood. On admission the patient weighed 4.3 kg, which was checked to ensure drugs were dosed correctly and as comparison to previous admission. A jugular blood sample was obtained for in-house biochemistry and haematology by the VN allocated to the case. The blood results demonstrated a normal state of proteinaemia and red blood cell count (Tables 2 and 3). A HR was obtained while feeling the femoral and pedal pulses to check if any pulse deficits were present. Heart auscultation allowed the veterinary surgeon to check for murmurs and arrhythmias. A RR was taken while observing respiratory effort. Chest auscultation was performed to listen to inspiratory and expiratory respiratory sounds. Mucous membrane (MM) colour and capillary refill time (CRT) were assessed. Judging these parameters in the patient pre-operatively is vital for maximising the safety of the anaesthetic process and judging physiological changes (Barker, 2013).

Table 2. Haematology results

Table 3. Blood biochemistry results

The patient was kennelled in the cat ward, away from dogs and prey species. A pheromone diffuser (Feliway®, Ceva) was plugged in, the kennel was lined with newspaper, a thick mattress, VetBed® (Pet Life) and litter tray. The patient had a nervous temperament therefore the ward door was kept closed. There was no traffic through the ward and the kennel was easily visible through windows.

Preparation and premedication

All equipment and consumables required for the anaesthetic were prepared by the VN. A check of the anaesthetic machine, breathing system and endotracheal (ET) tubes were carried out to ensure they were safe to use (Box 1). A Jackson-Rees modification Ayres T-piece was selected with a 0.5 litre closed ended reservoir bag and an adjustable pressure-limiting (APL) valve connected to active scavenging.

Box. 1Protocol for check of anaesthetic machine, breathing circuit and endotracheal tube

- Turn on oxygen cylinder outside at the beginning of the day and check level of oxygen on the pressure dial. Ensure it is labelled ‘in use’

- Plug in oxygen pipe and active scavenging on the anaesthetic machine

- Check the breathing circuit for fluid and/or debris. Attach breathing circuit to fresh gas outlet and scavenging

- Turn on oxygen flow meter to check function

- Turn off flow meter and press emergency flush button

- Turn vaporiser dial to check it turns smoothly

- Check the level of volatile agent in the vaporiser (refill if necessary, although this should have been done after operating the previous day)

- Check the breathing system for leaks

- Close the APL valve and plug the end of the circuit

- Turn on the oxygen flow to inflate the reservoir bag. Turn off the flow when adequately inflated. Check for deflation of the reservoir bag and listen for the sound of gas escaping

- When finished, ensure APL valve is left open

- Check the endotracheal (ET) tube for fluid and/or debris. Inflate the cuff and assess for deflation. Ensure cuff is fully deflated after check.

Premedication was administered as part of a balanced anaesthesia (Box 2). The patient was restrained safely for the administration of 0.15 mg medetomidine (Sedastart®, Animalcare) and 0.06 mg buprenorphine into the right quadriceps, and 1.2 mg meloxicam was administered sub-cutaneously. The lights were turned off and the patient observed in the kennel as the pre-medication took effect.

Box. 2Drug dosages

- Medetomidine 1 mg/ml — dose 0.035 mg/kg

- Buprenorphine 0.3 mg/ml — dose 0.014 mg/kg

- Meloxicam 5 mg/ml — dose 0.3 mg/kg

- Propofol 10 mg/ml — dose 1.2 mg/kg, maximum dose for one anaesthetic episode 24 mg/kg

- Lignocaine hydrochloride 20 mg/ml (approximately 2–4 mg per spray) — dose two sprays totalling 4–8 mg (NOAH Compendium, 2015)

- Atipamezole 5 mg/ml — dosed as half the volume of medetomidine administered — 0.08 mg/kg

- Methadone 10 mg/ml — dose 0.5 mg/kg

- Oral meloxicam 0.5 mg/ml (Metacam, Boehringer Ingelheim) — dose 0.05 mg/kg

Signs of sedation included muscle relaxation and reduced response to touch and noise stimulus. The neck was extended straight to maintain a patent airway, and the patient was covered with a blanket to aid normothermia. RR was monitored closely. Alpha-2-agonists can have depressive effects on respiration (Golden, 1998). The patient was moved to the induction room and positioned in right lateral recumbency for induction. The fur on the left forelimb was clipped over the cephalic vein and wiped with spirit. The vein was then raised for intravenous administration of 5.5 mg propofol (PropoFlo Plus®, Zoetis). The propofol was dosed with respect to the alpha-2 agonist used for premedication and to effect over 40 seconds. Consequently, a volume slightly higher than calculated was administered but deemed safe after calculating the maximum dose for one anaesthetic episode (NOAH Compendium, 2017b) (Box 2).

The VN intubated the patient with the use of a laryngoscope. Two sprays — approximately 6 mg — of lignocaine hydrochloride (Intubeaze®, Dechra) were administered prior to intubation, with 30 seconds allowed for laryngeal relaxation (Dechra, 2015). The patient was intubated with a 3.5 mm cuffed endotracheal (ET) tube and put on a flow rate of 2 litres of oxygen per minute (Box 3). Isoflurane (isocare®, Animal Care) was used as a maintenance inhalational agent. The anaesthetic depth of the patient was assessed before administering isoflurane (Figure 1). The patient's pupils were positioned ventrally. There was a very slow and light palpebral reflex and no significant jaw tone. The rate and quality of the pedal pulse was assessed. There was an initial period of post-induction apnoea, however the patient spontaneously respired after 45 seconds, at which point the isoflurane was administered at a concentration of 2%, respecting the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) of 1.68% required for anaesthesia in cats (NOAH Compendium, 2017a).

Box. 3Fresh gas flow rate calculations

(4.3 kg x 15 ml) x 12 = 774 ml/min

Minute volume (ml/min) = tidal volume (ml/kg) x respiratory rate (breaths/min)

|

Flow rate (litres/min) = minute volume (ml/min) x circuit factor(Ayres T-piece circuit factor = 2.5–3)

|

(Tidal volume estimation of 15 ml recommended by Murrell and Ford-Fennah, 2011)

Hair over each surgical site was removed with clippers and then the surgical site was aseptically prepared with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate solution (HiBiscrub®, Mölnlycke Health Care), warm water and cotton wool. In the operating theatre, a second scrub was performed and then sprayed with a solution of 4% chlorhexidine gluconate, water and 70% propyl alcohol.

Anaesthetic monitoring and intraoperative management

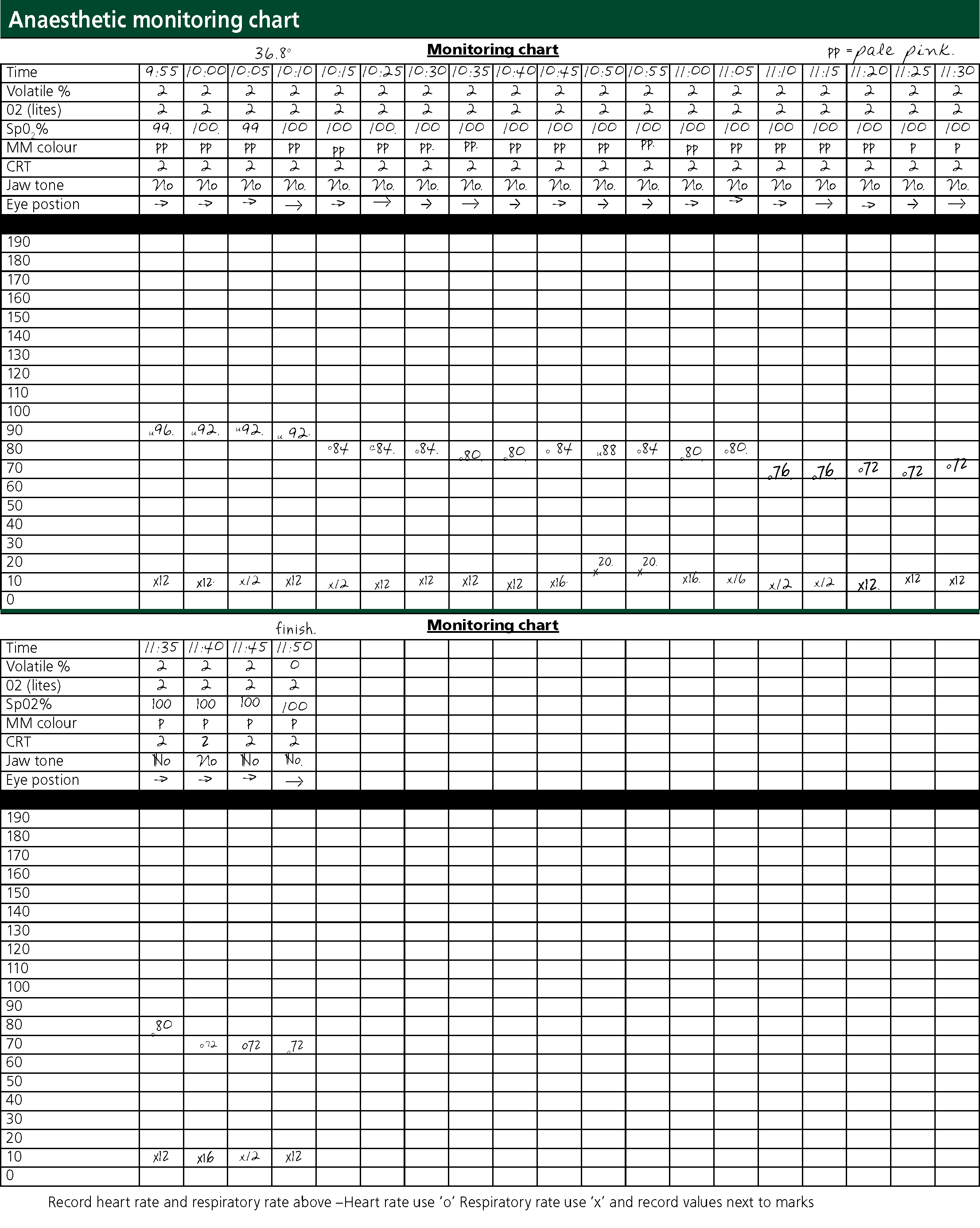

Throughout the anaesthetic, the RR and HR were manually monitored by an oesophageal stethoscope and observation. A pulse oximeter was placed on the patient's tongue to monitor haemoglobin oxygen saturation. Jaw tone, MM colour, CRT, eye position and palpebral reflex were monitored regularly to assess the plane of anaesthesia and whether the patient was at an appropriate depth for surgery (Figure 1, Box 4).

Box. 4Anaesthetic planes (Brouwer, 2000)

- Induction/voluntary excitement — the patient is conscious and may react to induction with an increased heart rate, respiratory rate or passing urine or faeces

- Involuntary excitement — the patient is unconscious and may have exaggerated reflexes and limb movements, irregular respiratory rate or vocalization

- Surgical anaesthesia

- Light — regular breathing, slow reflexes, eyeball starts to rotate downwards, weak jaw tone. Adequate for some investigations and procedures

- Medium — regular respiration, eyeball ventromedial, absent reflexes, greater muscle relaxation. Adequate for most surgery

- Deep — shallow, slow RR and may become more abdominal. HR slows and pulses weaken. Eye reflexes absent and pupil becomes central. This is unnecessarily deep for most procedures

- Overdose — thoracic muscles paralysed, respiratory difficulty and agonal gasping. Pulse is rapid and pupil begins to dilate

Eye lubricant (Lubrithal™, Dechra) was regularly applied to prevent corneal damage or ulceration (McMillan, 2015). Body temperature was to be taken by rectal thermometer, however the presence of faeces in the rectum made this difficult. A heat pad was used in theatre to aid maintenance of normothermia.

When the surgery was complete and wounds closed, the isoflurane was stopped and the reservoir bag emptied to remove residual isoflurane. Oxygen flow was continued for several minutes, but the ET tube was uncuffed and untied ready for removal. 0.35 mg atipamezole (Sedastop®, Animal Care) was injected into the lumbar muscle. The patient was extubated before laryngeal reflexes returned and moved to the kennel in the cat ward for recovery. A heat pad had warmed the bedding and close monitoring was continued.

The veterinary surgeon decided to wait until the patient was awake and could be accurately pain scored before further analgesia was administered.

Postoperative recovery and care

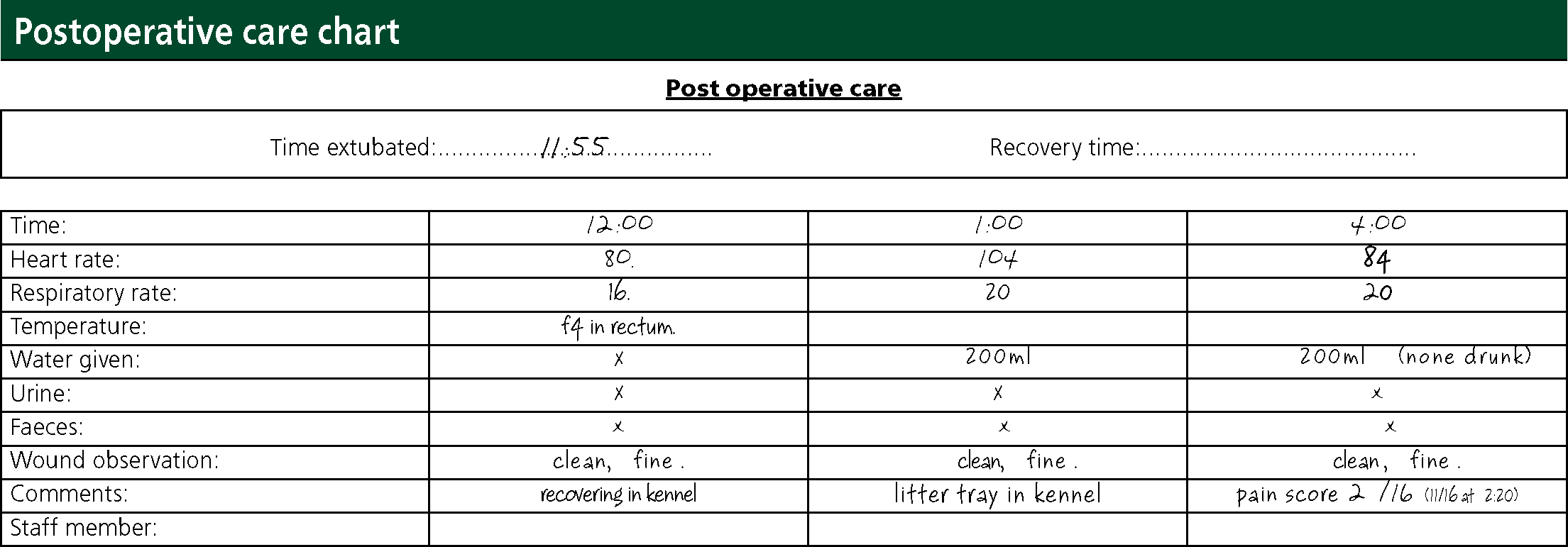

The patient was placed in right lateral recumbency to minimise pressure on the surgical site. An accurate rectal temperature was not obtained; the patient was kept on a heat pad and covered with a blanket to help maintain normothermia. Palpebral reflex, eye position and MM colour were monitored; HR, RR, urination, faecal output and wound assessment were also monitored and recorded on a post-operative monitoring chart 1 and 3 hours post operatively (Figure 2).

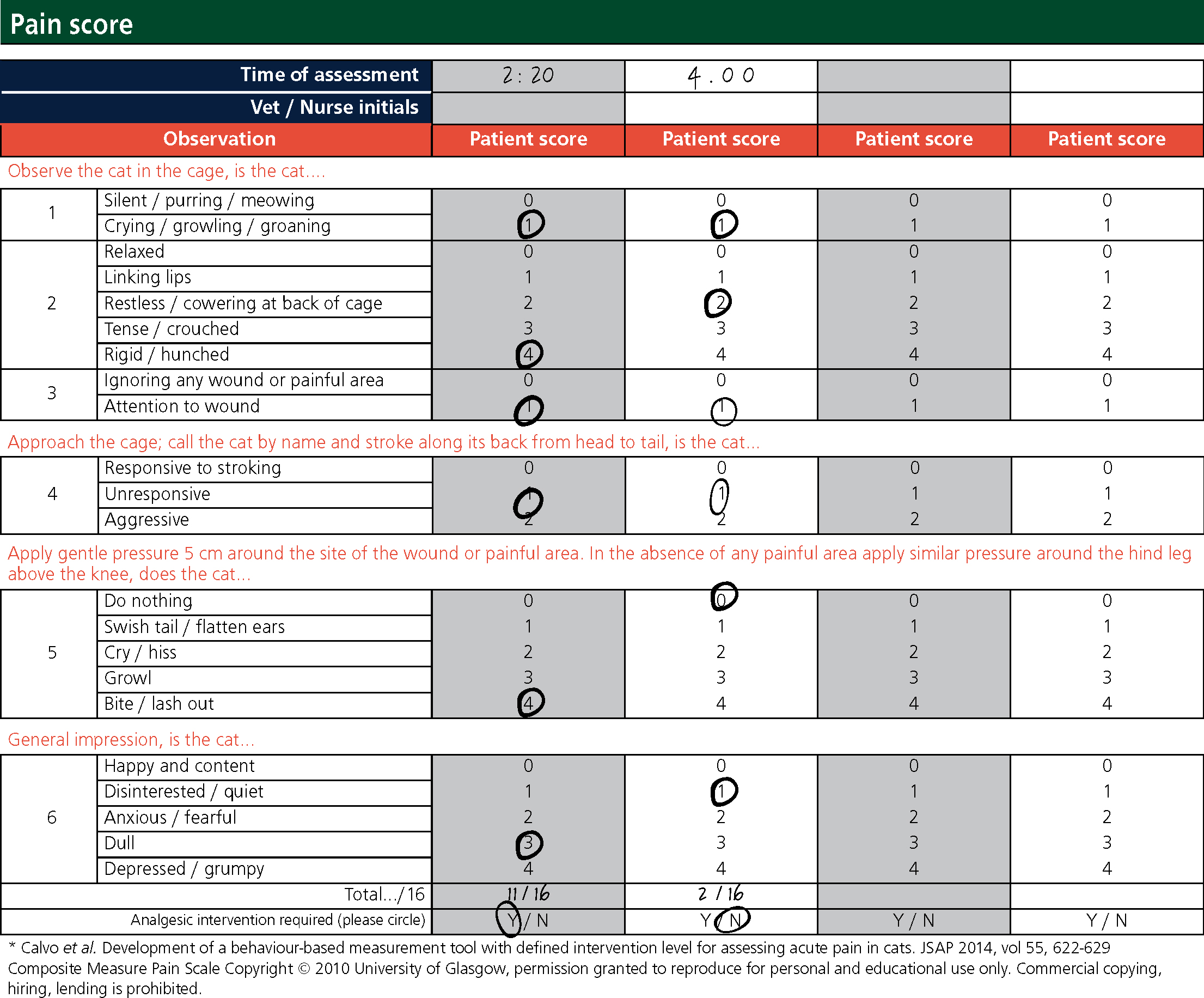

When the patient was adequately recovered, a Buster clic collar (Kruuse) was put on to minimise interference with the wounds. This was determined by the patient's eye position, mentation, and response to stimulus and surroundings. A litter tray and fresh water were put into the kennel and measured to monitor fluid intake. A Glasgow pain-scoring system was used around 2 hours and 4 hours post operatively to assess the need for analgesia (Figure 3). The VN reported pain scores to the veterinary surgeon and analgesia was prescribed; 2 mg methadone (Comfortan®, Dechra) was administered into the quadriceps muscle after the first pain score.

The veterinary surgeon discharged the patient that evening, approximately 6 hours after surgery, and advised the owners to continue with 0.08 mg sublingual buprenorphine three times a day, and 0.21 mg oral meloxicam once a day. A postoperative check was booked for 3 and 10 days’ time to reassess the patient's recovery.

Discussion

From previous hospitalisation, it was understood that the patient did not handle the practice environment very well and had a nervous, quiet temperament. Despite this, management of the ward environment allowed the premedication and recovery to go smoothly and without obvious signs of stress.

With respect to gold standard practice, intravenous access should have been established prior to premedication. Gaining venous access during a crisis may prove more difficult if there is circulatory collapse, meaning other routes of drug administration with slower onset are sought (Shellim, 2011). Furthermore, increasing the anaesthetic depth intravenously would have been an option and analgesia could also have been given intravenously. By inducing the patient without a cannula, safety of the patient, nurse and veterinary surgeon may have been compromised should the patient have ‘jumped off the needle’ while the propofol was taking effect with the needle in the vein.

The choice of breathing system was based on the weight of the patient. The Ayres T-piece — a non-rebreathing system — with APL valve allows for intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) if required, and also keeps resistance and dead space to a minimum. The respiration of the patient remained stable throughout, albeit relatively low at 12 respirations per minute. The patient maintained maximum oxygen saturation (Table 1 and Box 4) and there was no evidence of hypoventilation. If available, a capnograph would have been beneficial as a majority of anaesthetic issues are recognised by capnography before anaesthetists are aware (Killner, 2009). The VN managed the breathing system throughout the anaesthetic by checking connections, eliminating kinks in the system and compliance of the reservoir bag with the patient's respiration.

The anaesthetic was generally uneventful and the patient remained at a suitable medium plane of anaesthesia for surgery (Figure 1). The MMs were pink prior to premedication, however were paler pink for a majority of the surgery. This was not particularly concerning as vasoconstriction was to be anticipated from the medetomidine premedicant (Golden, 1998). CRT remained at 2 seconds however at times of painful surgical stimuli there was a mild increase in RR, HR and CRT. No increase in jaw tone or pedal reflex was observed. Central pupil position can indicate a deep plane of anaesthesia (Brouwer, 2000), however due to the mild cardiovascular responses to painful stimuli, it was decided to not decrease the inhalational agent. Despite these responses, no further analgesia was given. This was a vital time to intervene with analgesia and may have reduced the pain score achieved several hours post op (Figure 3).

Blood pressure monitoring did not take place. Hypotension under anaesthesia is not uncommon, especially due to vasodilation caused by inhalational agents (Hikasa, 1997), but may be rectified by decreasing the inhalational agent and administering fluid boluses (Mazzaferro and Wagner, 2001). The patient did not receive fluid therapy during the procedure meaning hypotension and fluid losses were not accounted for. Although no obvious issues arose, hypotension-related complications might have been pre-empted and prevented by the use of invasive or non-invasive monitoring.

Many factors can lead to perioperative hypothermia, for example the lack of skeletal muscle movement during anaesthesia (Archer, 2007). A reading of 36.8°C was obtained early on in the procedure, however the accuracy was questionable. The use of a temperature probe placed in the oesophagus could have been used if available. A heat mat was used to aid normothermia however efficacy of a heat mat partially depends on the heat penetrating through the bedding used. In theatre a thick VetBed® was used, restricting the amount of heat the patient could receive, therefore the use of a Bair Hugger™ may have been more appropriate. The heat pad was turned off in the kennel after recovery to prevent over heating, however the patient may have found it difficult to move off the heat pad sooner if they preferred and unfortunately the VN had to depend on subjective assessment of temperature because the large amount of faeces in the rectum may have meant rectal temperature readings were an underestimate of body temperature.

Pain scoring the patient provided an objective assessment indicating the need for further analgesia. Cats may conceal signs of pain and the patient's normal temperament mirrored some traits demonstrated by felines experiencing acute pain (Mathews et al, 2015). Multimodal analgesia was used by combining a full μ receptor agonist, a partial μ receptor agonist, an alpha-2-agonist and an NSAID, meaning different parts of the pain pathway were acted on to improve the analgesic effect. The use of methadone in the premedication could have been considered as lower pain scores and reduced need for additional analgesia has been demonstrated in patients premedicated with methadone as opposed to buprenorphine (Hunt et al, 2013). An epidural or nerve block could have also been considered for preven tative analgesia. Pre-empting pain prior to noxious stimuli is important to minimise the pain experienced immediately post operatively, which may lead to central sensitisation and further problems (Hoad, 2013a). In addition to this, the pain score was completed approximately 2 1/2 hours post surgery, and gave a score of 11 out of 16. The patient was alert 1 hour post surgery so a pain score could have been obtained earlier to assess comfort. Postoperative analgesia was especially important in this patient as cage rest is not indicated after excisional arthroplasty of a hip joint, where muscle tissue supporting the joint is to be maintained and strengthened through exercise to develop a synsarcosis.

The patient was discharged before being offered food approximately 6 hours after surgery. It is important to assess the level of appetite post operatively so intervention can be taken if necessary. Anaesthetic and surgical recovery can cause a 1.5 to two times increase in resting energy requirements due to the high calorie and amino acid demand for healing tissues (Hoad, 2013b). Although stress and discomfort may cause anorexia, the option for a patient to voluntarily receive enteral nutrition is important to promote the healing process (Firth, 2013). Therefore, food should have been offered as soon as the patient was suitably recovered.

Conclusion

The premedication, induction agent and maintenance protocol achieved a balanced anaesthesia with no apparent complications affecting recovery. The procedure was conducted smoothly with no immediate concerns regarding depth of anaesthesia or physiological distress.

The postoperative care and management of the recovery environment kept stress to a minimum, an important factor when considering the temperament of the patient. However, the analgesia protocol could have been revised to pre-empt pain and prevent the high pain score recorded post operatively. The incorporation of a full μ receptor agonist in the premedication may have reduced the requirement for further analgesic intervention, thus providing a more comfortable recovery overall. In contrast, the analgesia provided after the first pain score proved effective and the continuation of buprenorphine and meloxicam at home meant the patient had a comfortable recovery, as reported by the owner at postoperative check ups.

Additional patient monitors would have proved useful in monitoring the patient's temperature, respiratory gases and blood pressure, however the manual intermittent monitoring techniques and continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation proved successful. The use of fluid therapy to rectify losses during surgery should also have been considered to minimise hypotension and support fluid imbalances.

Key Points

- Thorough examination and stabilisation of a traumatised patient prior to surgery is paramount in supporting a safe anaesthetic.

- Checks of the anaesthetic machine, breathing circuit and endotracheal tube should always be performed prior to induction of anaesthesia.

- Monitoring of the patient and their vital parameters are to be conducted regularly throughout preparation, surgery and recovery and the anaesthetic and/or analgesia adjusted accordingly.

- Pre-emptive analgesia and regular pain scoring should be used to minimise pain experienced by the patient and maximise their welfare.

- Using a separate cat ward means the patient's environment may be better controlled and helps minimise unnecessary stress.