Nursing a variety of patients may present different challenges for veterinary nurses (RVN). An important challenge that the RVN may face, may be understanding the nutritional requirements for that particular patient while hospitalised, specifically canines and felines. Orpet and Welsh (2011) specifically consider nutrition within their Ability Model nursing care plan assessment framework. A nutrition plan should not be overlooked and should be incorporated into the nursing care plan. It can be easier to notice if the patient is eating their required daily amount of food if a plan for nutrition is created. If the patient has not eaten then a change to the patient's care and treatment plan sometimes occurs, possibly including more investigations or diagnostic procedures to determine why the patient is inappetent. A systematic approach of using assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation (APIE) may be applied to every patient which creates a nursing care plan and a holistic approach to nursing.

RVNs are aware of the importance of nutrition, however this does not guarantee that inpatients receive appropriate nutritional support. Appropriate nutritional support improves recovery from illness, reduces mortality, and improves responses to trauma and stress (Chan, 2004; Kathrani, 2016). Implementation of a nursing care plan specifically concentrating on nutrition requirements will assist the RVN in delivering the nutritional requirements. This may be achieved using a systematic approach using APIE — this article will discuss and explore this approach. Discussions regarding simple measures to aid the RVN when approaching and providing a nutrition plan for canines and felines will be included.

Importance of nutrition

Good nutritional support of hospitalised dogs and cats improves recovery from illness, reduces mortality and improves responses to trauma and stress (Chan, 2004). The purpose of providing nutritional support is to ensure the full nutritional requirement for the patient is being monitored. This can be accomplished by ensuring the provision of sufficient calories. The benefits of good nutrition have been proven to shorten hospitalisation in humans and dogs (Chambrier et al, 2012 ; Liu et al, 2012). It is vital that animals eat or drink as soon as possible after trauma, surgery or illness. This is to provide the essential nutritional requirements that are required for life (water, energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates, amino acids, essential fatty acids, minerals and vitamins). Baldwin et al (2010) discusses the importance of appropriate feeding throughout all life stages and how it can help prevent diet-associated diseases. Baldwin et al (2010) highlights just how important nutrition can be especially in unwell compromised animals.

Methodological approach to nutrition.

A successful approach to providing a nutrition plan includes four steps which comprise:

- Assessment in the form of an owner interview and nutritional history

- Planning which includes calculating energy requirements and calculating how much food to provide to meet daily requirements

- Implementing the nutrition plan by feeding the patient

- Evaluating the progress.

This approach uses the basis of all nursing care plans of APIE by delivering holistic patient focused care (Yura, and Walsh, 1967). These four steps, of approaching nursing care, were first introduced in 1967 and today human nurses and RVNs use adaptations of this method of nursing worldwide to ensure successful nursing.

Assessment

There is a vast amount of nutritional information available to ensure RVNs can provide a well-balanced diet to patients (FEDIAF, 2018). The owner should be approached for a dietary history and this should be acknowledged as part of the initial screening process of a nutritional assessment. This may assist the RVN in delivering a good standard of nutritional care and be beneficial in encouraging patients to eat while hospitalised.

It is recommended that each patient is considered individually after completion of a full clinical examination, including medical and nutritional history (Wells and Dumbrell, 2006: Freeman et al, 2011). Hospitalisation can be a stressful event for animals, therefore it can sometimes be beneficial to initially provide a hospitalised animal with the food that it typically receives at home. However, this may not always be appropriate. The RVN should individually assess the patient's current food intake and make appropriate dietary recommendations following consultation with a veterinary surgeon. Simply asking the owner what food their pet eats, bowl type, timing and frequency at home can be beneficial for RVNs when approaching in-appetence in a patient as this may encourage eating. The importance of recreating an animal's home environment to encourage spontaneous food intake has been discussed by Corbee and Kerkhoven (2014). It was suggested that creating a calm and relaxed atmosphere, including regular light cycles, will provide ideal conditions for encouraging food intake. To implement this care, it is further supported that RVNs are educated with the patient's normal daily routine including the type of nutrition they receive at home.

This nutritional assessment may be performed when the patient is admitted using a short form or questionnaire. A body condition score (Figures 1 and 2) is also recommended to be performed at this time and this can be useful to assess if a patient is underweight or overweight. It can also provide a baseline for comparison at a later stage in the patient's hospitalisation or further visits to the practice. The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) launched nutrition guidelines in 2011, RVNs may access and view the nutrition toolkit which includes a short diet history form and nutritional assessment checklist which may be useful when inter-viewing owners and gathering information. This may be accessed via: https://wsava.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/WSAVA-Global-Nutrition-Toolkit-English.pdf.

Planning

WSAVA (2011) have recommended that the decision about how much an animal should eat be based on a variety of published formulae to calculate the animal's resting energy requirement (RER), decreasing or increasing the amounts of food offered if weight gain and weight loss are apparent. Another highly discussed option is to calculate the animal's daily energy requirement (DER) (Thatcher et al, 2010). The animal's DER is based on the resting energy requirements (RER) with an addition of multiplying by a factor. There is suggestion that this method however is outdated.

There are several options for calculating RER, the two common methods are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Calculating resting energy requirements (RER)

| Two options for calculations of patient RER: |

| 1) 30(BW kg) +70 – If the animal weighs between 2 and 45 kg |

| 2) 70(BW kg)0.75 — a commonly used allometric calculation |

These calculations should be used as a guideline only and the amount of Kcal may be adjusted depending on weight gain or weight loss of the patient, and must always be considered an estimate of calorific needs.

Example of calculating RER in a 20 kg dog using option 1 from Table 1):

- (30 × 20 kg) + 70

- 600 + 70

- 670 Kcal (RER)

This information should be documented on the patient's hospitalisation sheet for all staff members to see. Doing so will ensure all staff members are informed of the quantity of expected oral intake of the patient required for them to achieve their RER, and highlight any discrepancies sooner (JoAnn, 2019).

RVNs that perform this organised approach are half way through the nursing process of creating a tailored nutrition plan for patients. The next important step is to apply the RER to calculate how much food to give to the patient. Baldwin et al (2010) discussed evaluating caloric density of pet food, and suggested that you may have to contact pet food manufacturer for this information. The food manufacturer is able to provide an accurate estimation of energy density within the chosen food.

An alternative and very simple method to calculate the energy content regardless of what type of food the patient is eating, is to use the information provided on a food label. This will be sufficient to calculate the Kcal per 100 g of the particular chosen food. Pet food labels contain a wealth of information, it is important for RVNs to have an understanding of how to analyse the information from them. Owners often ask veterinary staff which is the best food to feed their pets, therefore understanding food labels can be important (Chandler, 2014).

All animals will retrieve their nutrient energy from fat, protein and carbohydrates within the food. It is uncommon for food labels to include the carbohydrate amounts so a simple calculation of adding all the analytical constitutes together and subtracting from 100 will provide you with the carbohydrate amount.

An example of energy calculation of food from the analytical constituents from a food label can be seen in Table 2. An example of analytical constituents from a food label can be seen in Table 3. In this example there is 2.4 Kcal in each gram of food.

Table 2. Example of energy calculation of food from the analytical constituents from a food label

| Fat % (converted into grams by dividing by 1) x 3.5 |

| Protein % (converted into grams dividing by 1) x 8.5 |

| Carbohydrates % (converted into grams by dividing by 1) x 3.5 |

| Add totals together = Kcal per 100g of food |

Table 3.

Using the example from earlier, the amount of food that should be given daily is:

670 Kcal / 2.4 Kcal =279 grams of the selected food per day.

Implementation

The implementation part of the nursing process is delivering the planned nursing care to the patient, focused around stimulating oral eating successfully.

It is deemed best practice to assist and encourage oral feeding. There are many factors that may influence the route of providing nutrition including the nature of the disease or injury. For example, if a patient has a mandibular fracture then avoiding the oral cavity would be deemed preferable by placement of an oesophagostomy feeding tube. The ideal route of feeding should include as much of the gastroin-testinal system as possible, with the choice of route being discussed with the veterinary surgeon. In human hospitals assisted nutrition is implemented in critical patients with a review of their nutritional plan performed for those patients not orally eating at least two thirds of their estimated requirements (Chandler, 2012).

Placement of feeding tubes for nutritional support should be considered at the earliest convenience. Further discussion regarding feeding tubes is beyond the scope for this article (Table 4). Further reading is recommended (Collins, 2012).

Table 4. Different types of assisted feeding tubes

| Tube type | Body part involved |

|---|---|

| Naso oesophageal | Nose |

| Oesophagostomy | Oesophagus |

| Gastrostomy | Stomach |

| Enterostomy | Duodenum or jejunum |

| TPN | Parental nutrition |

If a patient requires oral feeding there are numerous approaches that may help. The choice of food can be important to ensuring success. Has the patient been hospitalised before? It can be very useful to read any previous hospitalisation sheets to see what type of food was offered and whether the patient ate well. This highlights the good use of hospitalisation sheets and the importance of documenting notes on nutrition as they can be an extremely useful aid for future use. Accurate record keeping is also considered an essential requirement according to the RCVS code of professional conduct (RCVS, 2019).

A palatable food may increase the chance of spontaneous food intake. Canned foods have higher moisture content than dry food and often higher fat and protein content, which will enhance palatability. If the patient receives dry food at home or is restricted to a certain dry food then simply adding water to increase the moisture content or softening the kibble can make it more attractive to the patient and also stimulate aromas. Most patients will be open to licking/lapping food but may not be open to chewing. Ensure any important information gathered, such as dietary intolerances/allergies, are incorporated into feeding plans when trying to tempt patients with food.

Cats are often strongly attached to the texture of food. It is recommended that different textures of foods are offered such as dry, wet or soups. Many cats may prefer a flat dish to a bowl, indicating the importance to consider bowl type. Some cats may like to be petted or hand fed small amounts of food, other cats may only eat when given a place to hide such as a cardboard box or simply covering the front of the kennel with a blanket. What may be successful in one animal may be unsuccessful in another, indicating that a holistic approach be used.

It is strongly advised not to offer multiple different foods all in the same offering as this can cause food aversions and ‘over face’ some animals. It is a process that should not be rushed to ensure success. Heating food to body temperature may have a positive impact on food intake, as does offering fresh food. Food that is not eaten within a short period after it is provided will likely not be eaten or be appealing to an animal.

RVNs should also take into consideration that hospitalised patients may be scared, nervous or potentially experiencing some degree of pain depending on the reason for hospitalisation. Improved results of spontaneous food intake have been seen in people with good pain control (Pilgrim, 2015). It may help if the patient has a sense of trust in the RVN and trying to increase the patient–nurse bond may improve chances of spontaneous eating (Collins, 2016). Other considerations may include removing the animal from the kennel and attempting to feed the patient in another room or even outside (canine patients) where they may feel more relaxed. It would also be wise to consider medical factors that might influence why a patient is not interested in eating, such as nausea. Some medications including opiods, antimicrobials, diuretics, immunosuppressants, and chemotherapeutics can have inhibitory effects on food intake. Therefore thinking about timings of food may be beneficial and avoiding attempts of food intake along-side some medication administration is recommended (Schiffman, 2018). Focusing on being successful in getting the patient to eat with numerous failed attempts may also have a negative effect. It must always be remembered that there may be an underlying reason for the inappetence, forcing the animal to eat could have negative impacts psychologically and clinically (Kathrani, 2016).

It is recommended that personal protective equipment (PPE) is used such as apron and gloves when handfeeding patients (Cote and Cohn, 2019). Please consider whether the animal is scared of loud noises from the ruffle of the apron or the bright colour of the gloves when hand feeding the patient. Hewson (2014) discussed that many in-patients have a negative experience of hospitalisation which can make clinical work more difficult. However, care must be taken if removing PPE especially in raw fed patients due to the zoonotic risk.

Syringe feeding may be considered and is tolerated well in some patients, however in the author's opinion this should be used as a last resort and with extreme care. A catheter tip syringe is more suitable for delivering thicker liquid diets either pre-prepared or blended. The tip of the syringe should be placed between the molar teeth and the cheek with the head in a normal position to prevent inhalation of the food, which can lead to aspiration pneumonia. If syringe feeding is resented, it should be stopped immediately. Force feeding should not be carried out as it can create food aversions. In a non-aggressive patient, a more suitable, safer alternative method using moist semi solid food or slurries may be attempted; these diets can be easily wiped onto the gums under the upper lip with your hand in the hope that the animal will lick and swallow the food. This method of placing small boluses of food in the mouth can be successful in stimulating the patient to then voluntary eat hand fed food or stimulate them to lick (Collins, 2012).

Contraindications for oral syringe feeding include the absence of a gag reflex and severe vomiting. Complications include aspiration pneumonia and food aversions and therefore should be used with extreme caution. Some veterinary practices have strict protocols in place preventing patients from being syringe fed due to the complications that may occur.

A more suitable last resort is informing the owners and asking for help, this may be to confirm their favourite food or treat. A more successful option is to organise an owner visit, as the owners may be more successful is stimulating spontaneous eating. This should be used carefully as there is the possibility that the animal will be distressed by the owner visit and also that the owners may be distressed at the thought of their pet not eating while hospitalised. It can however have positive outcomes.

Appetite-enhancing drugs such as cyproheptadine, mirtazapine, corticosteroids, and diazepam can be used, however, these must be used with caution as they can be seen to mask unknown problems (Quimby, 2016). Further reading is recommended. Consideration of their use should be included in the nutrition plan after discussion with a veterinary surgeon.

Evaluation

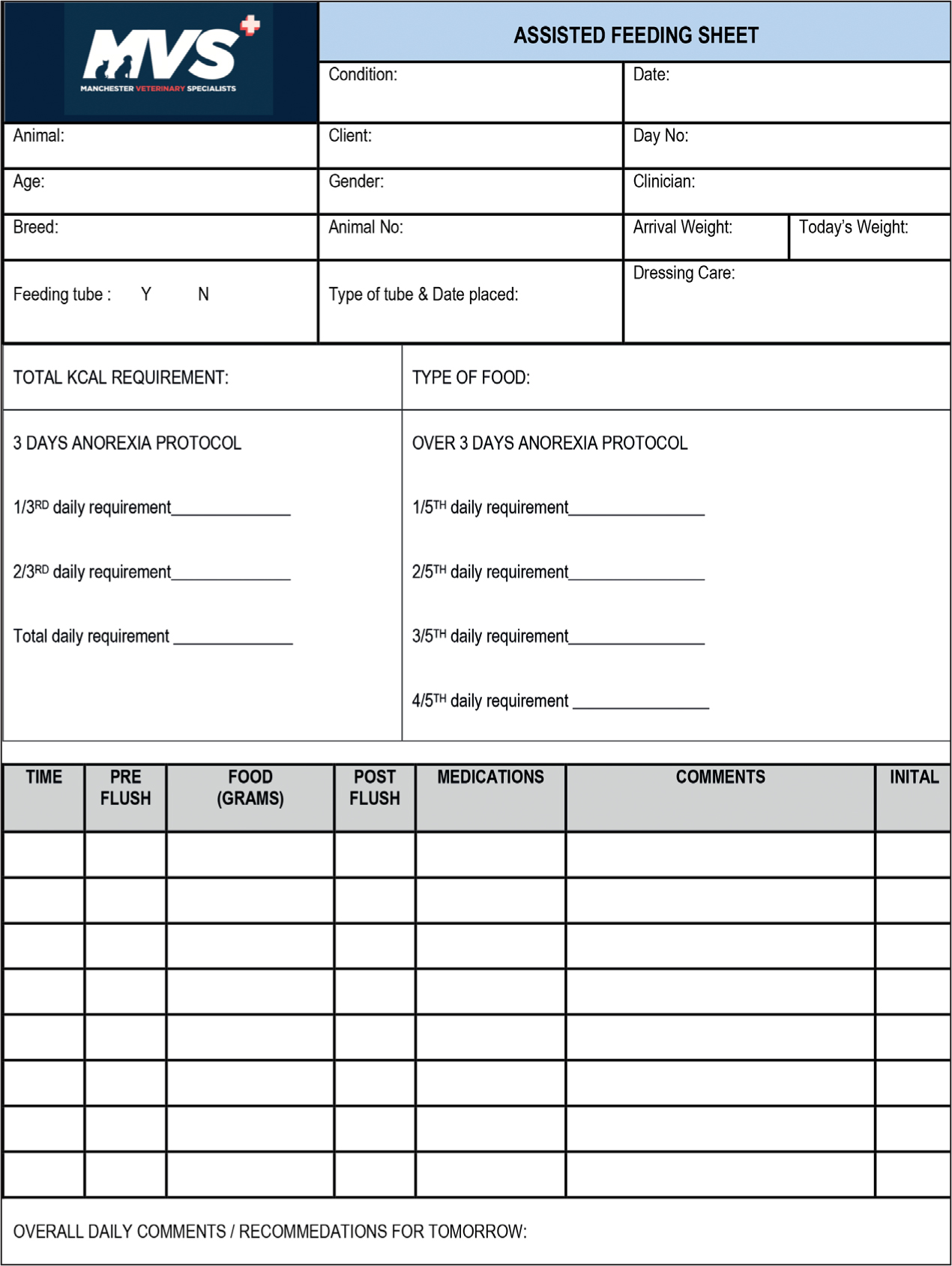

If attempts at spontaneous food intake have failed then a review and change of the basic feeding plan should be performed. It is recommended that the veterinary surgeon be consulted and a full clinical examination performed to eliminate deterioration in the patient's condition. If deterioration is noted then evaluation of the need for placement of assisted feeding tubes should be considered. If no deterioration is evident then use of a separate assisted feeding sheet with small frequent meals may help (Figure 3).

The assisted feeding sheet ensures an organised, planned, approach to the patient's nutrition is implemented. The form provides detailed information to multiple staff caring for the patient. This should increase the success of meeting the nutritional requirements for the patient. Lock (2011) discussed the success of a nursing nutrition plan, when one was implemented on an anorexic canine patient, concluding that it was highly beneficial to the patient and the nurses who were involved. Stating that the recovery of the patient was rapid with the primary aim of getting her to eat accomplished.

Conclusion

There is a growing awareness of the importance of good nutrition on people's health. As a result it is also recognised that food may be associated with disease. This awareness is mirrored in the veterinary industry. Veterinary nurse are aware of malnutrition and the effects it may have on an animal, and it is their duty of care to provide good nutrition to hospitalised patients. According to pet owners, veterinary staff are the best source of information on pet health care pet health care (Kogan, 2012). In the same way owners are the best source of nutritional information with regards to their pets. If RVNs become knowledgeable within the area of nutrition, this knowledge can be transferred to providing good nutrition to their patients. When pets are being fed as inpatients they are at their most vulnerable medically, increasing the need for good nutrition while they are hospitalised. By taking a systematic approach using Yura and Walsh's assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation (APIE) techniques, veterinary nurses may be more successful in assisting patients to orally intake their RER. This will ultimately lead to shorter recovery times and hopefully increased job satisfaction.

KEY POINTS

- The most important challenge that the registered veterinary nurse (RVN) may face, maybe the nutritional requirements for that particular patient while hospitalised.

- One of the goals of nutritional support is to provide the full nutritional requirement for the inpatient.

- A successful approach to providing a tailored nutrition plan includes four steps of the nursing process which include assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation (APIE).

- By taking a systematic approach using Yura and Walsh's APIE techniques, RVNs may be more successful in assisting patients to orally intake their resting energy requirements (RER).