Effective communication is key to work satisfaction and smooth running of any veterinary practice (Stobbs, 1999; Shaw, et al, 2010). The diverse and challenging nature of the work in veterinary nursing places great demands on the individuals to be competent in communicating face-to-face, on the telephone and in writing. In face-to-face communication, only 7% of the total impact of a message is attributed to the words spoken, while the remaining staggering 93% is attributed to non-verbal cues. These include tone of voice, volume and rate (paralinguistic features) of speech (38%) and facial expressions, body gestures and other forms of body language (55%) (Kinsey Goman, 2011). These percentages originate from studies conducted in the 1960s–70s, by Mehrabian and co-workers, which investigated people's feeling of ‘like’ and ‘dislike’ when exposed to statements spoken with conflicting verbal and nonverbal (vocal and facial) cues (Mehrabian, 1972). While these percentages cannot be applied indiscriminately to all communication situations, they do provide a very strong indication about a need for considerable care when writing — using only words (verbal information) to convey the intended message, without the aid of vocal and visual channels.

Emails are commonplace in the veterinary practice (Prendergast, 2011; Vanhorn and Clark, 2011). In addition to internal communication between staff members, emails are currently popular to communicate with clients. They can be used to respond to enquiries, or complaints, and to remind clients of upcoming treatments due for their animals. In written communication, people will make assumptions about the competence of the writers, and that of the company they represent, based on what they read (Booher, 2001). Client compliance can be increased by written communication, but only if the client feels they are receiving quality service from the veterinary healthcare team (Prendergast, 2011). A well written email, or letter, conforms to established conventions in format and contains carefully selected words that will not only accurately deliver the intended message, but also build trust in the mind of the client, which is necessary for compliance to be developed.

In recognising the importance of communication in the veterinary field and the need to prepare veterinary nursing students for work placements, a communication skills subject was delivered in the first year of BSc(Hons) in veterinary nursing. This is a 4-year programme jointly delivered by the Royal Veterinary College, University of London and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, taking place in Hong Kong (HK). Students experienced various teaching, learning and assessment strategies during the 28-contact hour subject. These strategies included lectures, group-based learning to produce a PowerPoint presentation on a specific veterinary nursing topic, role-play scenarios (e.g. giving owner advice on neutering) with actors utilising the Guide to the Veterinary Consultation based on the Calgary — Cambridge Model, GVCCCM (Gray, et al, 2006; Radford, et al, 2006), directed learning through the use of a workbook developed by McNae (unpub-lished) and Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). The medium of instruction for the subject, and indeed the entire degree programme, is English. Students on the programme have met the HK Polytechnic University's entry level requirement for English.

The study presented in this paper aimed to gain some insight into the email writing practices of veterinary nursing students and their learning experience in the communication skills subject. Specifically, it examined how these students responded in their learning of written communication in the form of an email.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 38 students were included in this study. This number represented the entire cohort of first year students enrolled into the BSc(Hons) in Veterinary Nursing programme in HK. English, for all the students except one, is the second or third language.

Data collection

Approximately 1 month prior to the commencement of the Communication Skills subject, students were given a 10-day period to write an email to the programme administration account, which students were familiar with, for the purpose of confirming their attendance at an external communication seminar. After approximately 20 hours of lectures and learning activities on the fundamentals of communication and different channels of communicating, the students were again asked to write an email, to the same email account, within a 2-day period. The purpose of this second email was to enable the students to propose veterinary or nursing technical terms, in Chinese and/or English, for discussion during the translation session that was to follow. The period between the two email exercises was approximately 2 months. A specific deadline was imposed and communicated explicitly to the students in each of the email exercises.

For consistency, all the student emails were examined by the same person for the key structure and components of an effective student email, in accordance with the checklist shown in Table 1. Explanations and guidelines of the requirements were based on standard business communication text books, such as Lamb and Peek (1995), Bilbow (2004) and Chapman (2007), and were discussed in a teaching session during the subject.

| Component | Guidelines/requirement |

|---|---|

| Recipient email address | Correct |

| Punctuality | Email received by the deadline given |

| Subject line | Relevant |

| Salutation | Names spelled correctly‘Dear Sir/Madam’, ‘Hello Judy’(‘To whom it may concern’ accepted) |

| Content | Concise and relevantMake reference to attachment if a documentis attached |

| Polite expression | ‘Thank you for your help’, ‘please feel free to contact me if…’, ‘sorry for my late reply’ |

| Close | Regards, Yours sincerely, Yours faithfully |

| Student name | First name and/or surname Stephanie, Kenny Chan, Wong Tai Ming |

| Student ID | Alpha-numeric, in full |

Late submissions were investigated for possible causes. Reasons provided by the students for late submissions were noted. Any content additional to the components listed in Table 1 were also noted.

Data analysis

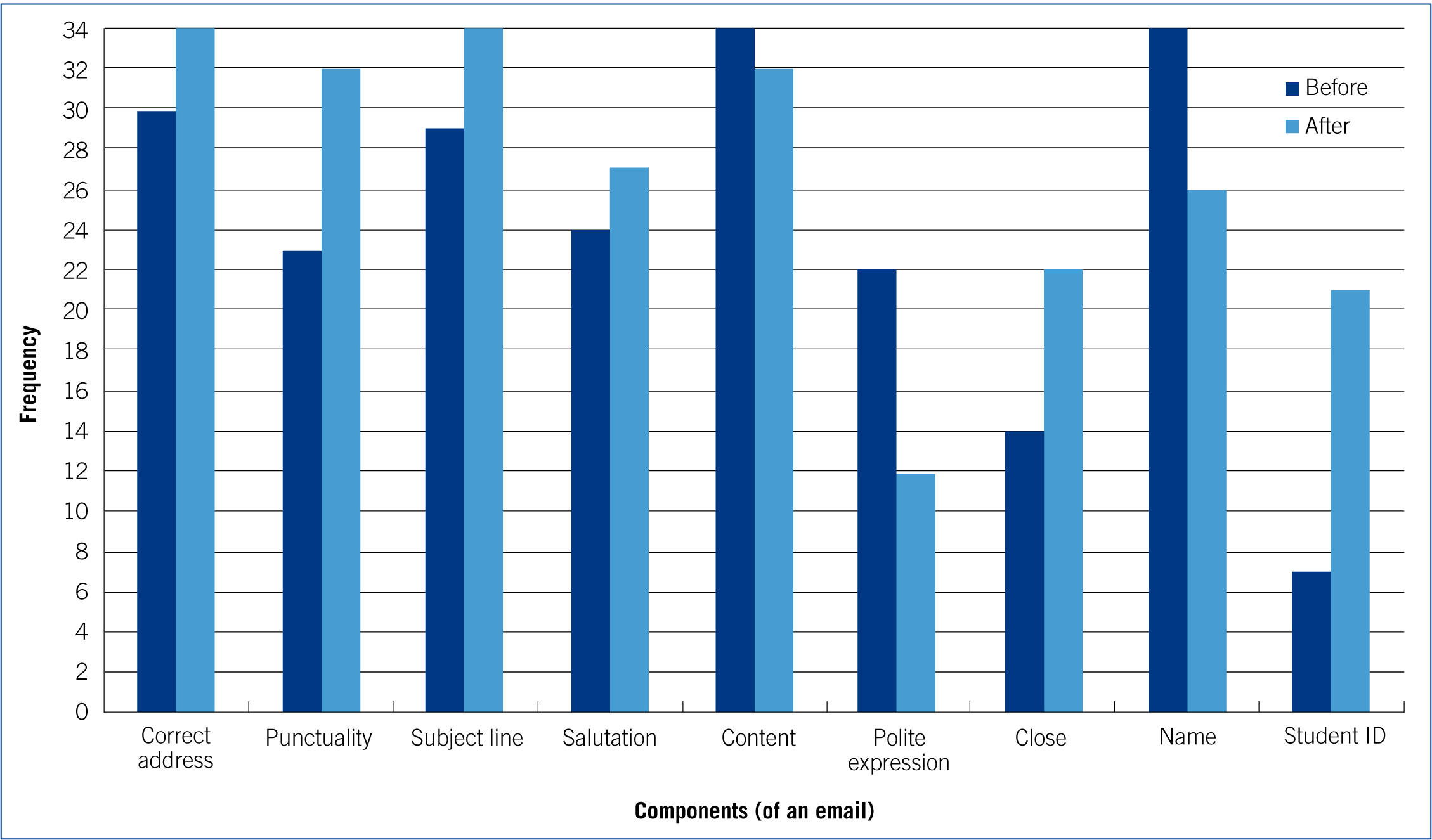

Students who did not submit an email prior to either event (communication seminar or translation session) taking place were excluded from data analysis. For each of the components listed in Table 1, the occurrence of correct presentation in the emails was recorded. Frequency charts were plotted for visual comparison between emails sent ‘before’ and ‘after’ commencement of the subject.

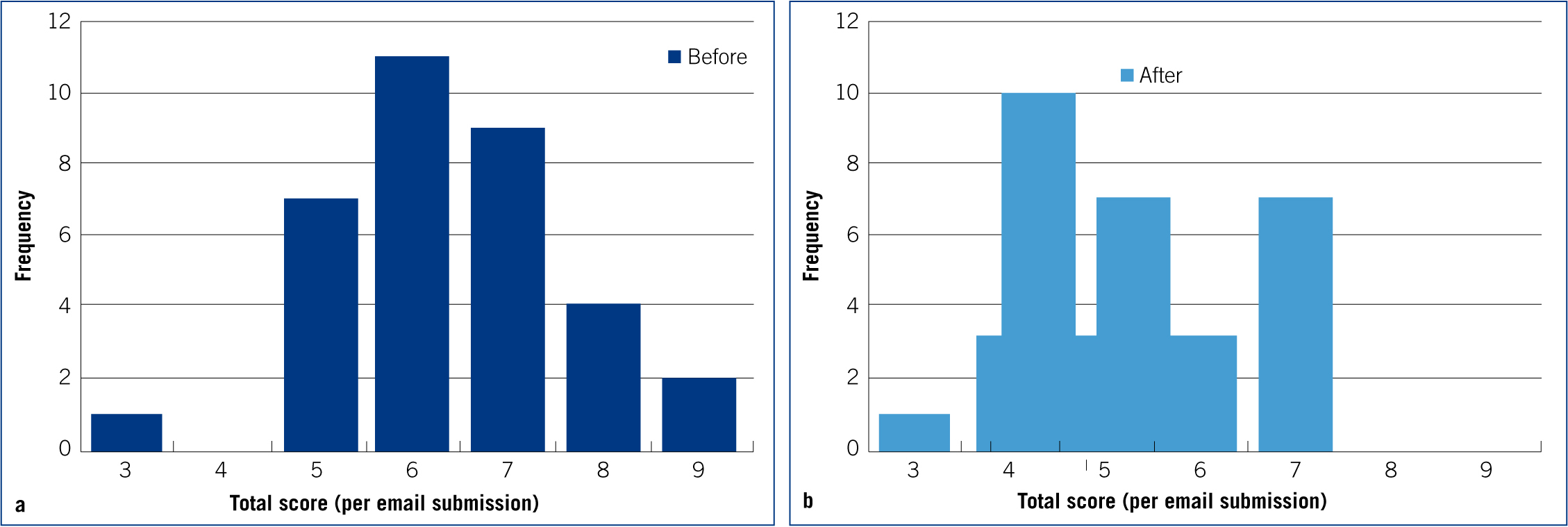

Also for each student email, a score of one point was given to each component correctly presented; the scores were added to give a total score. A maximum score of nine means the email contained all the components in the checklist (Table 1). Frequency charts were plotted for visual comparison of the scores attained by the students before and after commencement of the subject.

Determination of any difference between the two sets of scores was conducted using paired-samples t-test. A level of p<0.05 was considered to be significant. SPSS 19.0 for Windows was used to conduct statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 38 replies, representing the entire cohort of students, were received in the email exercise conducted before commencement of the subject, with 13 late submissions. A total of 34 replies were received for the second, after, email exercise, with only two late submissions. There were four students who did not submit an email prior to the translation session taking place (non-repliers) and the data sets of these individuals were excluded from further analysis.

Figure 1 shows the frequency of the components presented correctly in the student emails. An increase in compliance in the after email is indicated for six of the nine components; they are: ‘Correct address’; ‘Punctuality’; ‘Subject line’; ‘Salutation’; ‘Close’; and ‘Student ID’. Inclusion of Student ID showed greatest increase, followed by Punctuality. Conversely, ‘Polite expression’ showed the greatest decrease.

Of the 13 late replies in the before email, five were found to contain the wrong recipient email address. On closer inspection, all five replies were found to contain the same small typing error in the recipient email address, which was the omission of a letter. Among this group of senders with the wrong recipient address, one of them was also a non replier in the after email exercise. In addition to errors in the email address, other reasons for lateness reported by the students included forgetfulness and travel abroad.

Additional contents were only found in the before email. Table 2 shows the additional items found and the frequency of occurrence.

| Item | Frequency | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Smartphone email signature tag | 2 | ‘sent from my iphone’ |

| Pictograph/ emoticon | 3 | :) |

Figure 2a and b show the frequency of the different total scores given to the student emails and a right shift towards the higher scores can be seen in the after email. A total of 17 students (50%) attained scores of eight and nine (maximum), in contrast, a total of only six students (18%) in the before email. The paired-samples t-test analysis, at level p=0.057 (ie not <0.05), indicates that the mean score of the after email (mean = 7.06) was not significantly different to the mean score of the before email (mean = 6.38).

Discussion

A host of expectations are placed on university graduates by prospective employers and the community when these individuals enter the workforce. Having a sound and diverse communication skill set is essential for all healthcare professions to ensure patients receive optimal care (e.g. nursing and medicine (Faulkner, 1998; Chant, et al, 2002; Silverman, et al, 2005), and veterinary medicine (Baguley 2006)), the veterinary nursing profession is no exception. The absence of nonverbal cues, which convey emotions and attitudes (Carson, 2007; Kirwan, 2010), makes written communication all the more challenging to effective-ly get the message across to the receiver as intended. Good writing skills demand not only the use of the appropriate vocabulary and correct grammar, but format and structure are also important. Workplace email messages, like business letters, require all these criteria to be fulfilled. When well written, emails like any other format of written communication, can influence events and impact results (Forsyth, 2009), such as a client's compliance to the recommendations of a healthcare team for preventative health care or improving treatment result.

Results of this study show improvements in the students' email writing after exposure to a series of instructions and learning activities. For example, a session during the taught subject was spent discussing with students the differences between formal letters and emails. This was immediately followed by collectively analysing the students’ first, or before, emails. There was an increase in correct presentation for six out of the nine components considered prerequisites of an effective university student email. Also, the proportion of students who received high scores (eight or nine) for their emails was notably greater in the second (after) exercise.

The lack of statistical significance between the before and after email sets could be attributed to the fact that the purpose for each was different. From the student perspective, the first email was to ask for something (a place at an important event) and in conforming to social expectations, politeness was expressed by the majority and where lateness or absence was concerned, apologies were offered. Studies in computer-mediated communication have led Murphy and Levy (2006) to suggest that when email is seen purely as a medium for information transaction, as opposed to relationship building, the ‘politeness’ level in the writing could be reduced. This idea is supported by the notable decrease in ‘polite expression’ in the after email found in this study. It was possible that some students likened the purpose of the second email to assignment submission (provision of information), whereby the use of ‘Student ID’ is standard practice for the programme. The highest increase observed in the inclusion of the Student ID component in the second email would support this speculation. To further illustrate the notion that the second email was being perceived as more transactional in nature, some students used the ‘attach file’ function to submit their terms for translation discussion. Two students failed to make any reference to the attached document in the text body of the email which accounted for the two ‘Content’ missing cases in Figure 1. Besides possible perception of a difference in purpose of the emails, cultural influence on the perception of politeness, and how to express it in written form, cannot be precluded in view of the fact that nearly all the students in this study were non-native speakers of English. Murphy and Levy (2006) showed that the Australian and Korean academics used different politeness strategies which reflected varying levels of politeness in their emails.

This study found that it is worthwhile to investigate reportedly ‘missing’ emails. There can be many reasons why emails do not get sent successfully, the most common being address error (Lamb and Peek, 1995). As evidenced by the five late replies in the before email of this study, the recipient's address must be 100% correct. When an email is undeliverable, it should get bounced back along with a system message; the sender should take note of this email and study the address very closely to find the error in it. Some of the students were informed of the error they made in the email address. It is not unreasonable to speculate that one of the non-repliers in the after email exercise was due to a lack of awareness that the wrong email address was being used, as the address in the corresponding before email was also incorrect.

A feature called ‘auto-complete’ or ‘auto-filling’ present in most email systems, e.g. Microsoft Outlook, Hotmail and Yahoo!, can add to the problem of human typing error in addresses. In Outlook, this feature is turned on by default; as the first letter(s) of a name or email address is typed in the ‘To’ box, possible matches from a list of names and e-mail addresses that have been used previously appear for the user to select without the need to type further. This feature is only useful if the addresses were entered correctly the first time. If an address in the ‘auto-complete list’ is wrong (or outdated), deleting it from the list will curtail the problem.

This study by no means exhaustively examined all the aspects of effective email writing. The ability to write at varying levels of formality depending on the purpose, situation and target audience is very important (Chapman, 2007; Wallwork, 2011), and a skill that can improve through practise and experience. Structure and format of an email, as addressed in this study, conveys professionalism. However, the students’ choices of words or phrases were not heavily scrutinised, because the students may not have been certain about who the receiver was since the destination address (programme administration) did not carry a person's name. In some situations, students wrote their replies to the class representatives, who were their peers. Therefore, for ‘Salutation’ and ‘Polite expression’, ‘Hello / Hi…’ and ‘Thx/ Cheers’ were accepted, respectively, although these terms did not appear in the after email.

From this study, it is interesting to find that smartphones were being used by university students for correspondence related to academic work, as opposed to exclusively for social interaction. Although only two cases of this were found, should an upward trend develop, coupled with free wireless network access in the classroom, there may be an application in how teaching may be adapted to enhance student learning experience. Similar to ‘clickers’ or Audience Response Systems (ARS), which have been found to promote classroom interactions and student engagement (Molgaard, 2005; Patterson et al., 2010), smartphones and other personal mobile devices may be used to cast responses to questions embedded in a presentation real time. There are free polling systems/ software for mobile devices which are web based, whereby only internet access is required in order to respond without extra cost.

A final point of interest arising from this study is the use of emoticons, or pictographs in email communication. The use of emoticons exploded in popularity as computer-mediated means of communication, such as email, instant messaging and Facebook, found their way into people's everyday life. In the absence of nonverbal information, emoticons are a means in written communication to convey feelings and emotions, hence its name ‘emotional icons’ (Luor et al. 2010). A ‘smiley’, :-), offers a visual cue that can bring about a positive feeling in the receiver, in a similar way to a facial smile in traditional face-to-face communication. Studies on the impact and effect of emoticons have given rise to extensive findings (e.g. Walther and D'Addario, 2001; Luor et al. 2010). The results of the current study, however, are insufficient to add to the on-going debates. It is useful to note that as with any form of writing, the level of formality should be considered when deciding on the use of emoticons in emails. Some emoticons are very elaborate and the interpretation of many can be highly variable. Therefore, emoticons should be used only if they are conducive to communicating, or at the very least, do not cause otherwise avoidable confusion or misunderstanding.

Conclusion

There are guidelines and rules that make writing formal emails easier; results showed a class of first year university veterinary nursing students was receptive to learning these, and improvements were observed. The study described here is only one of the various ways in which students on the programme receive support to improve their skills in formal writing and communication, with a long-term goal to better prepare these individuals for future work in the veterinary field.