As suggested by Wise et al (2002) approximately 30% of the veterinary population is geriatric. Many of these animals require anaesthesia for dental care, diagnostic or surgical procedures. There is wide species and breed variation in lifespan, therefore there is not one specific age which can define ‘geriatric’. Instead, the term geriatric is normally used to define those animals that have reached 75–80% of their expected lifespan. The chronological age does not always match the physiological age, therefore each patient must be evaluated as an individual (Carpenter et al, 2005). Factors influencing the ageing process include: breed, size, genetics, nutrition and environment (Neiger-Aeschbacher, 2007). Age is not a disease, however the likelihood of morbidity increases with age, and age-related physiological changes and diseases will affect the anaesthetic management (Carpenter et al, 2005). Brodbelt et al demonstrated in 2007 that dogs 12 years old or more were approximately seven times as likely to experience an anaesthetic-related death than younger adult dogs, and cats aged 12 years and older were twice as likely to die as a result of anaesthesia (Brodbelt, 2007). These results combined with the increasing numbers of geriatric patients demonstrate a need for careful planning and preparation when anaesthetizing these animals. This article will discuss the physiology, pharmacology and anaesthetic management relevant to geriatric patients, concentrating on factors relevant to nurses.

Physiology

As stated by Carpenter et al (2005), ageing causes a progressive and irreversible decrease in functional reserves of the major organ systems, leading to altered responses to stressors and anaesthetic drugs. Changes in the organ system function may be covert until the patient is stressed by an illness, hospital stay, or general anaesthetic procedure (Table 1).

| Organ system | Age-related change | clinical effect/significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Decreased ventricular compliance and cardiac output, decreased blood volume and baroreceptor activity, increased risk of arrhythmias and chronic valvular disease | Decreased ability to maintain blood pressure, more rapid uptake of inhalational agents |

| Respiratory | Reduced lung elasticity, respiratory rate and tidal volume, reduced compliance, and respiratory muscle strength | Lower arterial oxygen concentration, decreased functional reserve |

| Hepatic | Liver mass decreases, decreasing liver function, decreased hepatic blood flow | Prolonged drug metabolism (prolonged recovery) hypoglycaemia, impaired coagulation |

| Renal | Reduced renal blood flow, reduction in functional nephrons, decreased glomerular filtration rate. Reduced ability to concentrate urine and hydrogen ion secretion | Monitor and maintain blood pressure under anaesthesia to ensure adequate renal perfusion. Judicious use of peri-operative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Nervous system | Neural degeneration decreases brain mass, decreased thermoregulation and neurotransmitter production, decreased sympathetic response to stress | Decreased requirement for anaesthetic agents (local, injectable and inhalational). More susceptible to hypothermia, stress and cardiovascular depression linked to anaesthesia |

Pharmacology

The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of sedative and anaesthetic drugs change with age (Neiger-Aeschbacher, 2007). Due to the changes in the central nervous system, geriatric animals have a decreased requirement for many drugs. Reduction in cardiac output means induction agents and boluses of injectable drugs take longer to exert an effect consequently it is easy to overdose.

Pre-operative assessment

As stated by Baetge and Matthews (2012), individual geriatric animals require different anaesthetic protocols depending on their concurrent illness, temperament, reason for anaesthesia and the clinical examination. A complete history should be taken, paying particular attention to previous and current medical complaints and current medications. Nurses should discuss with the veterinary surgeon the effect concurrent medications may have on the patient under anaesthesia and the protocol should be adjusted accordingly. A thorough clinical examination should be performed, paying particular attention to the cardiovascular system. Careful auscultation of the heart should be performed and if a cardiac murmur or arrhythmia is detected, a cardiac work-up (consisting of chest radiography, electrocardiogram, and echocardiogram) may be required. History about exercise tolerance is also useful when determining the significance of murmurs during the anaesthetic period. The peripheral pulse should be palpated simultaneously with cardiac auscultation to identify any pulse deficits. As suggested by Neiger-Aeschbacher (2007), diagnostic tests, such as haematology, serum biochemistry, urinalysis or imaging will be required in conjunction with the clinical examination. The extent of diagnostic tests will depend on the history, clinical examination and the planned procedure, however it is widely recommended that in geriatric patients a minimum of packed cell volume (PCV), total protein, serum urea, creatinine, and electrolytes should be performed. A urine specific gravity (USG) will be useful in determining whether any azotaemia is pre-renal or renal. There have been two studies examining the usefulness of pre-operative blood tests in dogs. Alef et al (2008) examined whether pre-operative haematology and biochemistry is of benefit in the general surgical dog population (not geriatrics) and discovered that the changes revealed by pre-operative screening were of little clinical relevance and did not prompt significant changes to the anaesthetic protocol. However, importantly, a study by Joubert in 2007 demonstrated that pre-anaesthetic screening in geriatric patients is important. New diagnoses were made in almost 30% of animals, based on the pre-anaesthetic screening and 40% of these did not undergo anaesthesia as a result of the diagnosis. Significantly, the pre-anaesthetic screening in this study did not just examine serum biochemistry and PCV but also included a USG, urine dipstick and full physical examination. This demonstrates the importance of blood tests in conjunction with the clinical examination and urine analysis in geriatric animals.

Anaesthetic plan

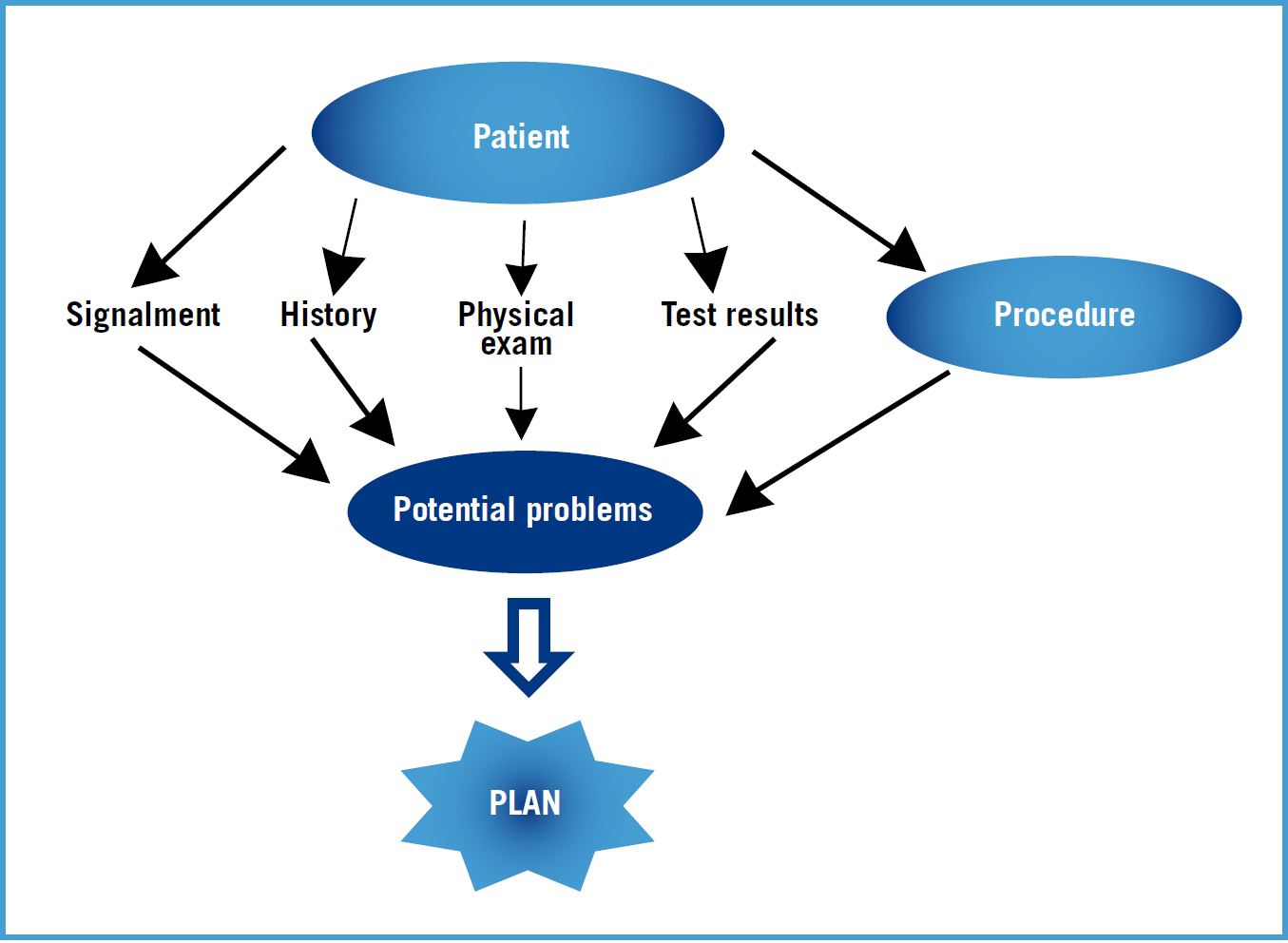

In the author's experience an anaesthetic plan should be formulated by the veterinary surgeon and the nurse before induction of anaesthesia. All aspects of anaesthesia should be discussed including: drugs; positioning; monitoring; recovery; anticipated problems and how these may be addressed (Figure 1).

An intravenous (IV) catheter is crucial for IV fluid and drug administration. If IV fluids are not required pre-operatively then placing the catheter after premedication reduces stress and anxiety for the patient and eases placement. If illness such as renal disease or diabetes is present, or hypovolaemia or dehydration, then IV fluid therapy will be required prior to anaesthesia. As stated by Neiger-Aeschbacher (2007), a balanced, isotonic electrolyte solution at 5–10 ml/kg/hour is often used, however the rate will depend on the patient's clinical examination results and history. If concurrent heart disease is present a more conservative IV fluid rate should be used.

Premedication

Pre-anaesthetic medication is useful to reduce anxiety and to facilitate IV catheter placement. This may be of particular importance in geriatric patients who are more prone to stress (Carpenter, 2005). Premedication also contributes to a balanced anaesthetic technique, reduces the amount of anaesthetic agents required and provides analgesia, all of which are beneficial in the geriatric patient, however careful drug and dose selection will be required, especially in those with underlying conditions (Table 2).

| Drug | Properties | Relevance to geriatrics | Precaution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenothiazine (acepromazine) | Anxiolysis sedation, long duration of action, not reversible, hypotension by vasodilation, hepatic metabolism | ⇑ sedation, ⇑ recovery time, ⇑ hypothermia, possible hypotension | Monitor blood pressure, use lower doses, avoid in cases of dehydration, liver dysfunction, coagulopathy or haemorrhage |

| Benzodiazepines | Anxiolysis, sedation, minimal cardiovascular effects, short acting, can cause excitement in some animals, hepatic metabolism | Can be reversed with flumazenil, minimal cardiovascular effects make them useful in geriatrics | |

| Full opioid agonists | Excellent analgesia, mild sedation, mild cardiovascular effects, dose-dependent bradycardia | ⇑ sedation, analgesia, minimal cardiovascular effects make them useful in geriatrics | Titrate dose to effect in sick geriatrics, effects can be reversed with naloxone |

| Partial opioid agonists | Minimal cardiovascular effects, less sedation than full opioids, good analgesia for mild to moderate pain, long acting | ||

| Mixed opioid agonist-antagonist (butorphanol) | Good sedation, minimal cardiovascular effects, poor analgesic | Minimal cardiovascular effects make it useful for geriatric sedation for non-painful procedures | |

| Alpha-2- agonists | Profound cardiovascular effects: vasoconstriction and ⇓ cardiac output, profound sedation, short acting, action, can be reversed | Profound decrease in cardiac output | Use with caution, only healthy geriatrics, especially avoid in patients with heart or cardiovascular disease |

Equipment preparation

All equipment required should be prepared prior to induction of anaesthesia. This includes equipment for intubation, drugs, IV fluids and emergency equipment and drugs (which will depend on the patient and the procedure). The anaesthetic machine and circuit should be properly set up and checked at the start of every anaesthetic.

Induction

Pre-oxygenation should be performed for 5 minutes using a tight-fitting mask, however if the patient is intolerant, then a flow-by technique, or mask with the diaphragm removed can be used. The specific IV induction agent used appears to be less important than the way it is administered. As stated by Neiger-Aeschbacher, 2007, increased age may reduce the amount of induction agent required and the reduced cardiac output will increase the time taken for the drug to exert an effect. Therefore it is important to administer induction agents slowly to effect in geriatric patients, and an IV catheter greatly aids this. A co-induction agent with minimal cardiovascular effects such as midazolam or fentanyl could be considered to reduce the amount of induction agent required and therefore the side effects, however only fentanyl has been demonstrated to reduce the dose of propofol required (Covey-Crump and Murison, 2008). Mask inductions are not generally recommended in geriatric patients, due to the stress they cause. Induction and maintenance of anaesthesia with inhalant anaesthetics alone in dogs was associated with a 5.9 times increase in the likelihood of anaesthetic-related death (Brodbelt, 2008).

Patient positioning

As reminded by Carpenter et al (2005), geriatric animals may have some degree of muscle wasting or arthritis. They may also be less flexible than younger animals so care should be taken when they are positioned for surgery or radiography that their legs are not secured too tightly which may cause pain during anaesthesia and in the post-operative period. The limbs should be well supported and padded to avoid pain and excess pressure on joints (Figure 2).

Maintenance

General anaesthesia is made up of three components: narcosis, analgesia and muscle relaxation. Each part can contribute to varying degrees depending on the patient and procedure. As suggested by Baetge and Matthews (2012), in geriatric patients a combination of drugs to create balanced anaesthesia is usually the most ideal solution. For example, premedications will decrease induction drug requirements, while infiltration of local anaesthetics will reduce the need for intraoperative analgesia. Maintenance with inhalational agents offers advantages such as minimal reliance on hepatic metabolism and the ease and speed of adjusting anaesthetic depth, however their dose-dependent cardiovascular and respiratory effects, especially hypotension, mean that the lowest possible amount should be used. The use of adjunctive drugs such as nitrous oxide or continuous rate infusions of drugs such as lidocaine may reduce inhalational agent requirements and therefore the side effects. It should also be remembered that geriatric patients have a decreased requirement for inhalational agents.

Monitoring and support

As stated by Neiger-Aeschbacher, (2007), both sedated and anaesthetized animals need careful monitoring. The extent will depend on the disease, procedure and equipment availability but should be as complete and continuous as possible. Peripheral pulse rate, rhythm and quality, respiratory rate, depth and pattern, body temperature and ideally blood pressure should be monitored and recorded as a minimum, along with regular assessment of depth of anaesthesia. The nurse should discuss with the veterinary surgeon a plan for emergencies and also for minimum and maximum tolerated values for parameters such as blood pressure and heart rate and the treatment options available.

Geriatrics have a decreased thermoregulatory capacity (Carpenter et al, 2005) so every effort should be made to maintain body temperature throughout anaesthesia including after premedication, and in the recovery period. This can be performed with forced air blankets, warming fluids, heat pads and bubble wrap. Temperature should be monitored regularly. Hypothermia has serious consequences including a reduction in cardiac output, arrhythmias, a prolonged recovery, and a reduction in inhalational agent requirements (Murison, 2001).

Recovery

Nurses should ensure geriatric patients have well-padded bedding or even orthopaedic foam matresses to prevent pain and discomfort in the post-operative period (Figure 3). Geriatric animals are more easily stressed than younger animals and less tolerant of a busy hospital environment, therefore every effort should be made to minimize stress and discomfort. Patient warming and checking of rectal temperature should be continued until the patient is normothermic. Along with a prolonged recovery and reduced mobility, hypothermia in the recovery period causes shivering which increases oxygen consumption by 200–300% (Carpenter et al, 2005). This may lead to hypoxia which may be especially relevant in the geriatric animal with significant loss in cardiopulmonary reserve, therefore oxygen supplementation should be considered until the patient is normothermic. As suggested by Neiger-Aeschbacher (2007) adequate nutrition and access to water should be initiated as soon as possible and appropriate periods of rest and sleep should be allowed without disturbance to enhance recovery. Regular pain assessments should be performed and adequate analgesia provided, not only for the pain due to surgery but also for any pain due to existing conditions such as arthritis.

General anaesthesia versus sedation

Clients and veterinary surgeons often prefer sedation to general anaesthesia in geriatric patients as it is perceived to be ‘safer’ (author's experience). Brodbelt (2007, 2008), found no changes in death rates in the general dog and cat population with general anaesthesia versus sedation. It very much depends on the individual patient and the procedure, however, in the author's experience, which is supported by Baetge and Matthews (2012), patients undergoing general anaesthesia are normally monitored more closely, have a secured airway thus allowing provision of 100% oxygen, provision of intermittent positive pressure ventilation and preventing aspiration of regurgitated stomach contents. Patients under anaesthesia may also be more likely to receive warming and IV fluids. Also in geriatrics, concurrent illnesses or conditions may prevent the use of high enough doses of sedatives meaning the patient is inadequately sedated and stressed. All these factors combined and the lack of evidence to the contrary, demonstrate sedation does not appear to be less risky than general anaesthesia in geriatrics and a risk:beneft ratio must be weighed up.

Future considerations

A stated by Baetge and Matthews (2012) post-operative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is an accepted problem in human medicine. POCD is associated with normal consciousness but impairment of memory, concentration, language comprehension, and social integration. It is thought that POCD may resolve within 3 months but may also be permanent, with no known treatment. It is currently unknown whether a similar problem exists for veterinary patients, however, there may be anecdotal evidence that it does exist. The cause of POCD in humans is unclear, however, cerebrovascular disease, cerebral hypoperfusion, genetic susceptibility, alteration in neurotransmitter function, neurohumoral stress, and central nervous system inflammatory phenomenon have all been suggested (Ouellette and Ouellette, 2010). The literature on human POCD is limited and difficult to interpret, however it may be an area of development and interest in veterinary patients in the future; since POCD is associated with age, it seems likely that, with the increase in geriatric patients, this problem night be expected to be seen in veterinary medicine.

Conclusions

Age is not a disease, however, because geriatric dogs and cats are more likely to experience anaesthetic-related deaths than younger dogs and cats there is a need for extra caution and preparation when faced with anaesthetizing the geriatric patient. Communication with the veterinary surgeon is vital to formulate an anaesthetic plan unique to every individual situation and means problems can be quickly anticipated and treated. The most important parts of anaesthesia for the geriatric patient are not the obvious things such as drug selection, but instead are good nursing care, a thorough pre-operative assessment to identify underlying disease and the way drugs are used and administered rather than the individual drugs themselves. A knowledge of the physiological changes in geriatric patients enables nurses to provide optimal patient care throughout the peri-operative period. Although considerable care should be taken, with the right preparation and monitoring, the geriatric patient can usually be anaesthetized safely and comfortably.