A loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) was brought into the rescue centre by a member of the public — the turtle has sustained a traumatic head injury (Figure 1).

Patient details

Species: Loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta)

Age: Adult

Sex: Female

Wound location: Dorsal skull

Clinical history

A loggerhead sea turtle, that became known as ‘Chanel’, arrived at the rescue centre 2 months before the authors' arrival, after being rescued by a member of the public who had found her washed up on the beach. She had sustained a large, traumatic head injury, which was suspected to have occurred during a collision with a boat propeller. Sea turtles are prone to getting entangled in fishing gear and such incidents may often result in injuries or drowning. They may also fall victim to collisions with speed boats, especially near nesting beaches. Several cases of deliberately killed animals washing ashore have also been reported from different sites.

The wound was reported as a large, extensive injury, with parts of the brain tissue exposed and fractured bone fragments present.

Summary of current wound management

The initial management by the rescue centre involved reducing haemorrhaging and stabilising the patient for further treatment, followed by cleaning the wound with povidone-iodine antiseptic solution (Vetasept®, Animal care Ltd) diluted 1:10 with water, and debridement, including the removal of bone fragments by a veterinary surgeon.

More recent management also involved mechanical debridement and the application of Manuka honey (Activon®, Advancis Medical). This was followed by gauze swabs impregnated with petroleum jelly (Vaseline®, Unilever UK Ltd), in an attempt to provide waterproofing and to hold the dressing in place, which was carried out every 2 days.

During the time at the centre she had not voluntarily eaten, but faeces had been passed. Feeding was carried out via oral stomach tubing of a fish slurry. Passing the stomach tube became increasingly difficult and successful feeding was managed weekly. It was also proving to be quite stressful for everyone involved, and could have eventually led to significant health consequences for the patient. Supportive pain relief and fluid therapy was also being administered.

Wound assessment

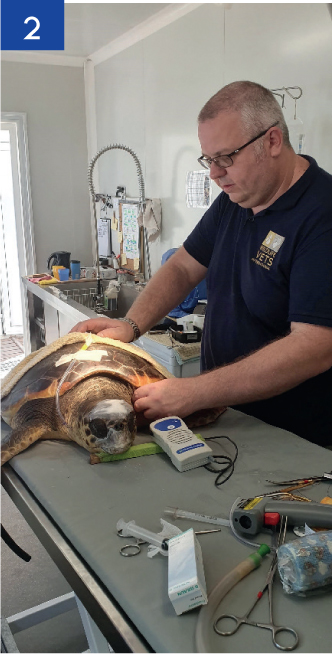

The assessment of the wound was carried out during sedation using medetomidine/ketamine, while the patient was having an oesophageal feeding tube placed by the veterinary team (Figure 2). Placing a feeding tube would allow maintenance of hydration and the optimal nutrition to be given during the rehabilitation period with minimal stress and would also supply essential nutrition needed for wound healing.

The previous dressing was removed (Manuka honey with waterproof gauze swab). The wound measured approximately 6 cm in length, 2 cm in depth and the width was irregular, with the widest area measuring 3 cm. The tissue involved was both the epidermis and dermis. During the visual examination, the tissue appeared pale grey and moist with minimal exudate. Some evidence of granulation tissue was evident, as no brain exposure or bone was seen at this stage (Figure 1). Granulation tissue in turtles appears pale pink/grey compared with reddish tissue seen in mammals. Some necrotic tissue was evident.

As a result of the presence of inflammation and a very strong putrid smell coming from the wound, it was deemed to be infected. At this stage ideally, before starting antibiotic treatment, a bacterial culture and sensitivity swab would have been taken to isolate the exact bacteria present within the wound. The best time to culture a wound is following lavage to eliminate superficial contaminants.

Management plan

The management plan included:

- Continue to treat as an open wound, supporting it through the inflammatory stage by reducing contamination and necrotic tissue, and controlling the presence of infection

- Change the lavage solution currently being used to a more appropriate solution

- Correcting nutrition.

Day one

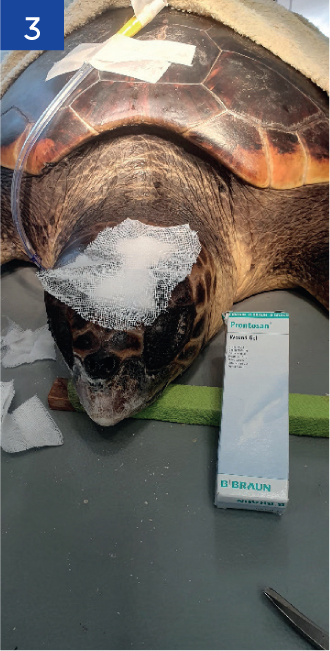

After removing the previous dressing, the wound was flushed with copious amounts of warm saline solution. Some loose necrotic tissue was removed using a curette and the wound was dried using a sterile gauze swab. Prontosan® gel (B. Braun Medical Ltd) was applied, followed by gauze swabs impregnated with petroleum jelly to waterproof and to keep the dressing in place (Figures 3 and 4).

Follow up — day two

The following day the patient had fully recovered from the sedation. Water was passed down the oesophageal tube to check for correct placement and to provide hydration along with subcutaneous fluids that were still being given. It is essential with reptiles to make sure that they are re-hydrated before attempting to feed after a period of anorexia and then to start off at low levels and gradually increase to prevent re-feeding syndrome. This is because excessive calories and protein causes a rapid uptake of glucose from the blood stream into the cells, which takes potassium and phosphorous with it leading to imbalances.

Follow up

Day three

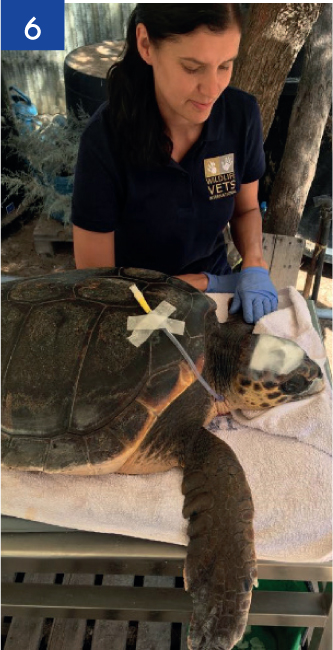

Two days following the first treatment, the dressing was removed. When removing the top layer of gauze coated with the Vaseline®, a puddle of water was visible underneath. This showed it was not completely waterproof, but the wound appeared healthier, pale pink in some areas and the smell had reduced dramatically (Figure 5). It was decided to continue with the same plan and to re-apply a dressing following debridement, lavage and Prontosan® gel application (Figure 6). It was requested that this would be removed after 2 days and a re-assessment carried out.

On this day after adequate hydration and making sure the tube was in the correct position, diluted Emeraid piscivore® (Lafeber) was given.

The manufacturers of Emeraid® recommend when using one of their semi-elemental formulations, to feed 0.5% bodyweight at first feed, 1% bodyweight at the second feed and 2% bodyweight at the third feed. Semi-elemental diets are highly digestible and are well-suited for the critical patient having difficulty absorbing nutrients.

The tube was flushed with water before and afterwards, and then the turtle was positioned upright for 20 minutes to prevent regurgitation (Figure 7).

Outcome

Following the first treatment of copious flushing, debridement, and the use of polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) to help control infection and remove any biofilm (Butcher, 2012), the wound started to improve in appearance and odour.

The visit to the centre was only short and follow up on this case was difficult. Over the following 2 months the centre reported that ‘Chanel’ was recovering well, had begun eating by herself and had now the ability to dive and rest at the bottom of her tank, which is a crucial part of her recovery process.

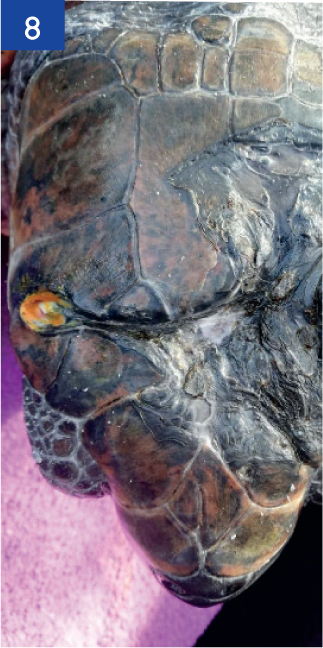

Today, 10 months following the visit, the wound is completely healed, and ‘Chanel’ continues to do well (Figure 8). She is looking to be release back into the wild once the water temperature increases.

Discussion

Lavage is a vital part of wound management and was essential in this case. All traumatic injuries in turtles are considered to be contaminated by the ocean environment and in the case of beach stranding may be grossly contaminated by debris.

To reduce contamination and bacteria associated with infection it was important to lavage the wound at every dressing change. Use of an ideal isotonic solution and avoiding the use of disinfectants that could damage skin cells and delay the healing process, is also necessary.

Previously the wound was flushed using an antiseptic agent: povidone-iodine (Vetasept®) at a dilution of 1:10. To minimise the possible cytotoxic effects and to improve efficacy, a dilution of 1:100 may be prudent if povidone-iodine is the treatment of choice (Berkelman et al, 1982; Burks, 1998).

Using a large volume of solution and the correct pressure is the key to effective cleansing of the wound. Too high pressure may drive some bacteria/particles deeper into the wound; too low, and it may not be sufficient to move material out of the wound. Research has shown that ideal pressure is 8-15psi. This can be achieved using a 20 ml syringe and a 19g needle for delivery (Bianchi, 2000).

Lavage would also reveal the wound to allow better assessment, and rehydrate necrotic tissue for easier removal. In the case of reptiles there was no risk of contamination of the wound from surrounding fur/feathers, but the surrounding area would still need to be cleaned/lavage to remove any bacterial contamination present.

The aim of debridement is to remove any necrotic tissue and debris from the wound bed. Any necrotic tissue present would lengthen the inflammatory stage of healing and delay proliferation. Therefore, debridement should be carried out as needed to minimise infection and promote healing (Anderson, 2017):

- Mechanical — physical removal of necrotic tissue

- Autolytic — by applying a hydrogel (Prontosan gel®).

To encourage granulation and promote healing it is necessary to provide a suitable wound environment. A wound maintained within a moist environment has been proven to heal 50–60% faster than a wound left to dry out (Winter, 1962). This can be achieved with the use of a hydrogel, for example Intrasite® (Smith & Nephew).

Unfortunately, taking a bacterial swab was not feasible because of financial constraint, but an appropriate antibiotic was selected. Ceftazadine was chosen as it is a broad-spectrum antibiotic with strong activity against Gram-negative organisms (Davies and Klingenberg, 2019). The application of antimicrobial topical treatments were also used, along with lavage and debridement to reduce bacteria levels.

Although Manuka honey has effective antimicrobial properties, there were concerns about the possible osmotic effects of Manuka honey around the brain area. It was therefore decided to change to Prontosan gel®.

Prontosan gel® contains purified water and two other key ingredients — PHMB (polyhexanide 0.1%), which is a broadspectrum antimicrobial agent, and betaine (undecylenamidopropyl 0.1%), which is a surfactant that penetrates and disturbs the biofilm extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Prontosan acts physically to destroy the structure of the biofilm.

Protecting the wound from further contamination using dressings and avoiding factors that may further delay healing is crucial.

There are 12 factors that may delay healing (Knottenbelt, 2003). Table 1 describes the factors that may delay the healing process for this case. Dry docking of turtles during wound management is generally discouraged because it may impede circulation, which would also impede wound healing (Mettee and Norton, 2017).

Table 1. Factors that affect healing

| Factors that may delay healing | Actions | |

|---|---|---|

| Necrotic tissue | Necrotic tissue was present at the edges of the wound and would lengthen the inflammatory stage of healing and delay proliferation |

|

| Infection | Due to the aetiology of the wound and contamination, infection was inevitableOpportunistic bacterial infections are likely in impaired tissue and healing will be delayed |

|

| Poor nutritional status | The patient was anorexic. If poor nutrition occurs the ability to fight infection is significantly delayed and granulation tissue formation is affected |

|

| Paucity of blood/oxygen supply | Dry docking during wound management may impede circulation and thus healing |

|

| Toxicity | Antiseptic solutions could damage skin cells and delay the healing process. If used, appropriate dilutions should be used. They should never be used in healthy granulation |

|

Waterproof dressings should be applied. In this case, the use of a waterproof dressing, for example Tegaderm® (3M) glued into place on top of dressing may have helped with waterproofing, and would protect the wound more effectively. The use of Debrisoft® (L&R Medical UK Ltd) may have been beneficial as a gentler form of mechanical debridement in this sensitive area. Regular tank water changes should always be carried out to prevent further contamination of the wound.

Conclusion

To be able to spend more time at the centre to monitor cases, overcome difficulties and to see the wound through the healing process would have been beneficial. This experience highlighted the importance of knowing the appearance of the different stages of wound healing and exudate levels in reptiles and gave an insight into the challenges seen when managing wounds in aquatic species, and the importance of maintaining nutrition and correcting hydration prior to any assisted feeding.

KEY POINTS

- A holistic approach is required in woundcare management.

- Proactive open wound management is required for the best outcome.

- The wellbeing of the turtle was of paramount importance.

- A slow rate of progression of wound healing is normal.