Compassion, both giving and receiving, entails an emotional response. It goes beyond acts of basic care and is likely to involve generosity, giving a little more than you have to, kindness, and real dialogue (Frank, 2004).

‘Real dialogue’ is an essential component of compassion and of good nursing care in general. It involves more than communication, which is defined as the accurate giving and receiving of a message. It is spoken human to human rather than clinician to patient/owner. Real dialogue shows interest, does not stereotype, includes honesty and may indeed require courage at times. In order for a person to develop compassion towards others, first he or she must have a basis on which to cultivate compassion, and that basis is the ability to connect to one's own feelings.

Compassionate behaviours towards self

Step 1

Be alive to your internal world: it is essential for healthcare personnel to recognise their capacity to tolerate distress, their emotional state and their levels of fatigue and then to take measures to maintain resilience or improve matters if needed. Research on compassion is limited, however there is growing evidence that enhancing self compassion increases wellbeing (Allen and Leary, 2010) and resilience (Smeets et al, 2014), thus enhancing the capacity to be compassionate towards others. Mindfulness, defined as the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we are doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what is going on around us (Mindful.org, 2016) has been advocated as a significant aid to developing compassion.

It is important throughout the day, and especially the working day, to take moments to stop, think, reflect and acknowledge any feelings, a process that need not be highly time consuming. It is essential to be aware of these considerations, as they could potentially provide insight into what might be inhibiting such an approach (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015). Many opportunities are available to help discover a mindfulness approach; interested parties are directed to the RCVS Mind Matters initiative.

Step 2

Support the development of systems at work that give you and your colleagues space to reflect on what you are doing: good regular interactions between team members are important as they enable members to know when colleagues are experiencing difficulty within or outside of the workplace, thus enabling additional support for them if required. Teams can make rules about simple caring actions for their colleagues. Such actions may be as basic as providing a listening ear or ensuring someone gets a rest break, or may be more complex, such as suggesting a colleague take a step-back from an emotional case or seek external help from a counsellor or other healthcare professional.

Step 3

If there is a system problem, do not work around it or ignore it: addressing organisational problems, via the appropriate channels, is better for you, your colleagues and your patients. It is important to remember that the standard you walk by is the standard you accept (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015). The attention that senior staff members and managers give to achieving financial balance and meeting targets can deeply affect the priorities and behaviours of staff throughout an organisation. When finance and productivity are perceived as being the only things that matter, it can have profound negative effects on the way staff feel about the value placed on their work as care-givers. Such a situation makes it more difficult for staff to then cope with the inevitable emotional and psychological demands of the job (Firth-Cozens and Cornwell, 2009). Cornwell and Goodrich (2009) advocated that practitioners should be provided with a forum for open and honest dialogue about their experiences of delivering care. They stated that by providing staff with a safe and recrimination-free environment in which to discuss the everyday challenges, frustrations and pressures of the job, helps to remind busy staff that every patient and their loved ones are unique. Such an approach provides support for individuals, encourages communication within the team and can help to improve team dynamics. Good team relations make a difference not only to the quality of the interactions among team members, but also to the quality of care delivered to the patients (Cornwell and Goodrich, 2009).

Compassionate behaviours towards owners

Step 4

Remember that owners will often be in a high level of distress when they arrive at the practice: treat them as real people, not simply as customers, nor as the diagnosis of their pet. Information becomes difficult to assimilate when people are in a highly emotional or anxious state (Pagano, 2016). It is essential therefore to remember the importance of basic communication and questioning skills; these include, but are not limited to, effective listening, careful consideration of paralinguistics (which includes the tone and pitch of the voice), and the use of positive body language such as making eye contact and adopting a receptive body posture — arms open with palms exposed, or resting comfortably on the consulting table or relaxed at the side of the body if standing. Such postures are generally considered as a sign of openness, accessibility, and an overall willingness to listen and interact (Gorman, 2016). Consideration must also be given to the location of any discussion; a quiet environment is essential in order to avoid distractions and hence breakdowns in communication. Such an environment will also provide privacy to distressed owners and hence demonstrate compassion and a genuine empathy towards their situation.

Step 5

Show yourself as a person and not just a uniform: some readers may be familiar with the name Kate Granger, an NHS doctor who sadly passed away earlier this year. Kate founded the national campaign ‘Hello my name is’ after herself receiving a diagnosis of terminal cancer. During a hospital stay in 2013, where Kate was informed that her cancer was sadly not treatable, she made the stark observation that many of the staff looking after her, including the doctor who gave her the diagnosis, failed to introduce themselves before delivering her care. Kate firmly believed that this simple act was more than just about common courtesy, claiming that introductions were about making a human connection between one human being who is suffering and vulnerable, and another human being who wishes to help. Her ethos was that ‘hello my name is’ was the first rung on the ladder to providing truly person-centred, compassionate care. If such findings are extrapolated to the field of veterinary medicine, it seems prudent to suggest that a similar approach should be adopted. Anecdotally it is reported that many veterinary personnel do indeed introduce themselves (Figure 1), hence clients are often familiar with the name of their veterinary surgeon or nurse, however shift changes do occur and locum staff may take over cases mid-way through treatment. The simple act of introducing oneself as the new healthcare provider can provide comfort, reassurance and demonstrate compassion during distressing times. Further information about the campaign can be found at: www.hellomynameis.org.uk

Step 6

Pay attention and be respectful: when in consultations or discussions with owners, ensure your full attention is on them. With computers in many modern day consulting rooms, staff must be mindful not to let this intrude on the discussion. While there may be useful information available on the computer screen, staff should endeavour to read the patient notes prior to the appointment and avoid inputting data while actually conversing with the client.

It is essential to let the owner tell you what they want to without interruption; give them the opportunity to tell you their pre-constructed narrative, rather than diving straight in with a series of questions to delineate detail, such as the exact colour and frequency of the diarrhoea! While such an approach will likely yield a lot of non-pertinent information, active interest displayed towards the owner should help to establish trust and encourage honest and open communication (Tidy, 2015). Summarising is then a useful technique to use after the owner discussion in order to provide a run-down of what they have told you as you understand it, omitting any narrative. For example: ‘So Mr Proctor, from what I understand Scamp has not been consuming the whole of his food ration for 3 days now and since yesterday he is only consuming the meat portion of his food and leaving the biscuits. Is that correct?’ A nod of approval or expressed agreement with the story can be taken as confirmation of understanding. If not, then further discussion will prove necessary. Such dialogue is essential not only to ensure accurate detail is recorded, but to make owners feel that their contribution towards their pets care is valued.

Compassionate behaviours towards patients

Step 7

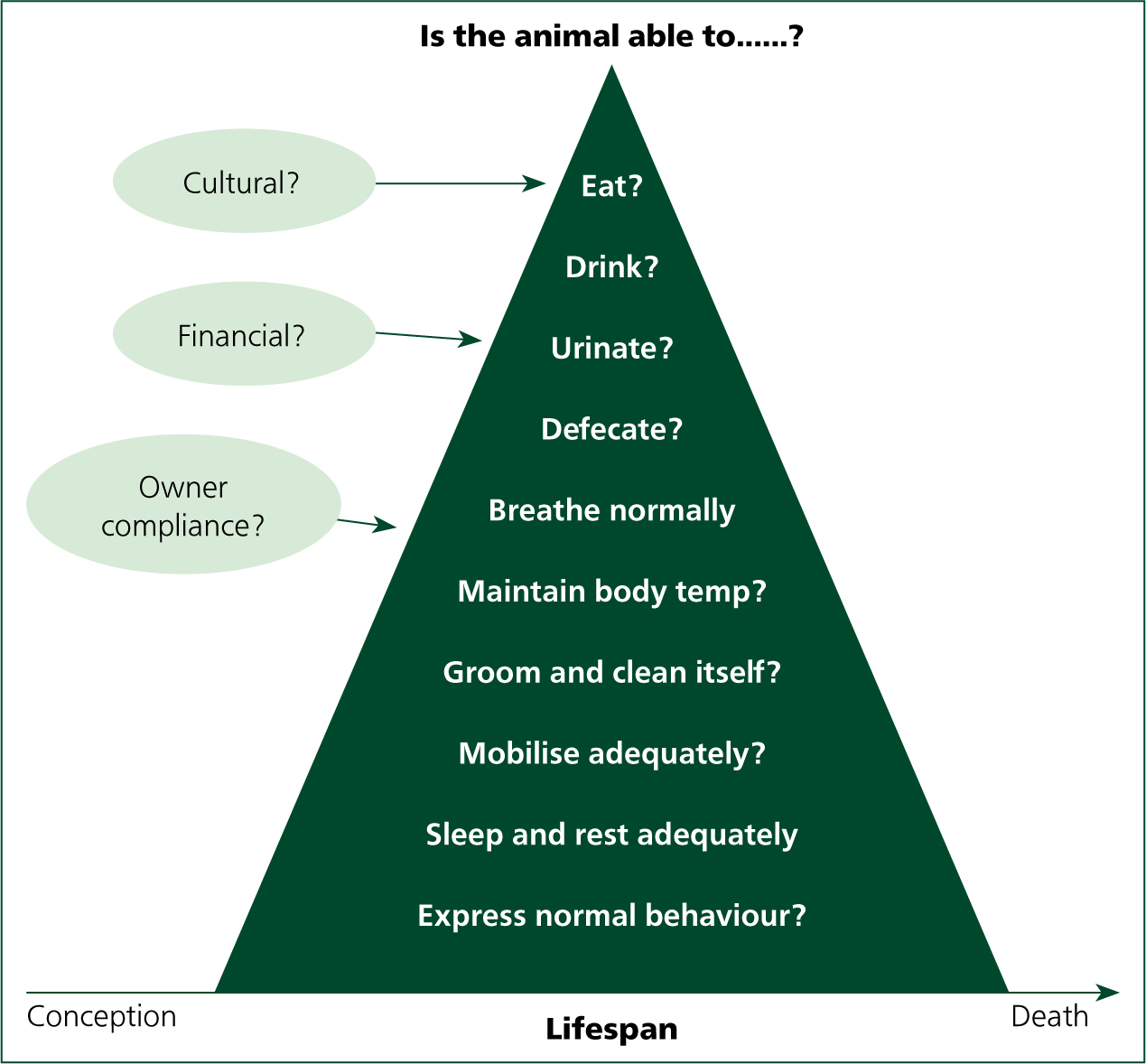

Provide individualised and patient-specific care rather than condition focused care: this concept is not new in veterinary nursing; models of nursing are now well established within the veterinary nursing curriculum and articles have been appearing in veterinary nursing press since as early as 2000 (Joiner, 2000). Despite the familiarity with the concept of a more holistic, patient-focused approach to care, anecdotally, the adoption of such concepts within veterinary practice does not appear to be widespread, despite the fact that student veterinary nurses must appraise nursing models and implement care plans as part of their study. There are also a number of published reports from qualified veterinary nurses who have implemented such an approach to patient care (Lock, 2011; Brown, 2012; Wager and Welsh, 2013), and reported that such concepts can be incorporated into veterinary practice and do improve levels of patient care. It is beyond the remit of this article to appraise models of nursing and care plans in depth, however the author strongly believes that the implementation of such an approach to patient management is synonymous with compassionate nursing care. Many readers will be familiar with the Orpet and Jeffery Ability Model (OJAM) (Orpet and Jeffery, 2007) which to date is the only published model of care specifically designed for veterinary use. The OJAM (2007) framework requires the veterinary nurse to consider ten patient ‘abilities’ on which to base their patient assessment, and the implementation and evaluation of their nursing care. The aim of the framework is to address any inabilities before they become more problematic for the patient and to help reduce the risk of any potential problems becoming actual problems through lack of action on the nurse's behalf (Wager and Welsh, 2013) (Figure 2).

The success of the model is also aided by incorporating and adhering to the key stages of the nursing process:

Compassion is a key element in all of the above stages, right from the initial assessment stage which, as well as observation of the patient and discussion with the admitting veterinary surgeon, will require discussion with the owner. Compassionate dialogue with owners will likely yield valuable information which will enable the veterinary nurse to deliver care specific to that patient. It is only through taking the time to converse with owners and asking them for information regarding their companion that details such as favourite brands/flavours of food, type of food bowl used, toileting commands and personality traits will be revealed (Figure 3).

Such information is essential in order to provide patient-focused care. Introducing yourself by name and explaining to owners why such information is essential will likely be met with enthusiasm. Such information is then crucial to the nursing diagnosis and planning stages as pertinent information can be used to identify actual problems and predict potential problems, and then this information used to set goals for the patient and establish how these goals will be met via appropriate nursing interventions. A traditionally ‘medical’ approach to care would see such interventions focused on the problems caused by the particular dysfunctional body part or system and the need for medications to stop such problems. A more patient-centred approach however places emphasis on setting goals and nursing interventions on the patient's individual requirements and any specific needs arising from the nursing assessment. Of course, such information is only beneficial if all staff involved in the care are aware of the specific needs of the patient. Information provided should be detailed, specifying exactly what is to be done, how often it should be done, how much should be done and in what order in relation to other veterinary and veterinary nursing activities (Wager and Welsh, 2013). Patient notes often contain vague detail such as ‘feed little and often’. Such information is open to interpretation depending on the individual staff member reading it. A clearer way to express this would be to specify what type of food to feed, what quantity to feed and the frequency of feeding. This should ensure that any member of staff caring for the patient can follow the instruction and measure to what extent any goals have been achieved (Wager and Welsh, 2013). An example of such details included on a patient's care plan is detailed in Box 1.

Example extract from a nursing care plan

| Problem (nursing diagnosis) | Short-term goal | Nursing intervention | Reassess/evaluation | Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inappetence — therefore not consuming sufficient nutrition to meet demands | Achieve voluntary intake of food | Mix 25 g of adult maintenance biscuits with 1 level teaspoon of tuna. Ensure that food is presented on a plate | Fluffy consumed 1/2 of this ration directly from the plate after some fuss and verbal encouragement | Repeat at 13.00 |