References

Motivating and engaging others: driving practice change

Abstract

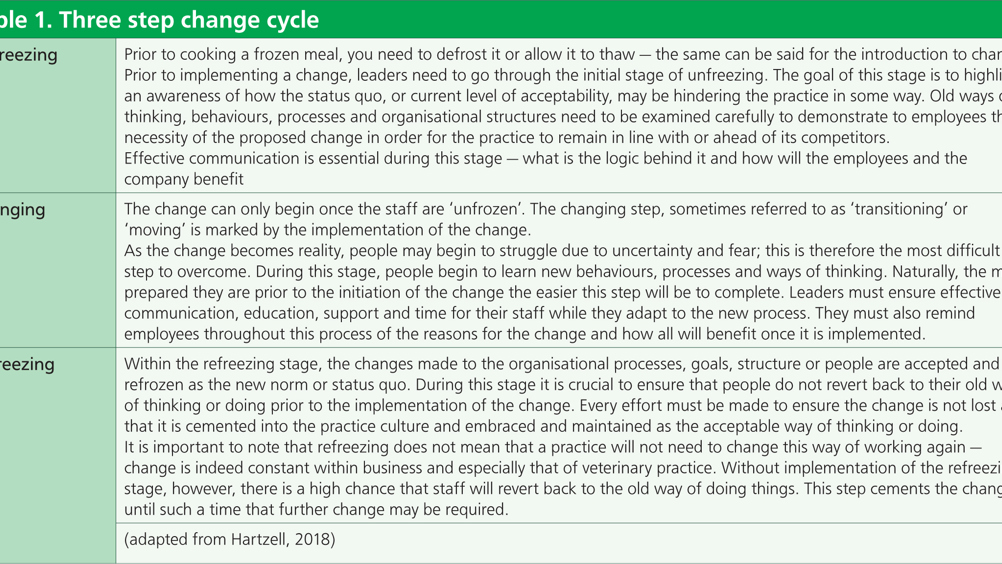

Do changes introduced within your practice go no further; are they met with negativism, disinterest or even resistance? Are new ideas dismissed by a culture of complacency and inertia? Change can be a difficult and even uncomfortable process to go through and when poorly handled can lead to high levels of stress amongst the team. The ability to change is crucial, however, to the success of any organisation and has never been more important than it is in today's evolving healthcare environment. To manage change effectively requires time and dedication. This article aims to introduce novice/aspiring leaders to elements of change theory and make practical suggestions as to how to plan and implement a change in practice.

Snaith and Hardy (2014) suggested often-perceived small changes such as the recruitment of a new team member, or the move to a different equipment supplier, can be as disruptive and challenging as a move to a new premises.

According to Stobbs (2004) change is a strange phenomenon; it is an inevitable part of life, and is often a very positive experience. After change has occurred, employees often say that they prefer the new procedures or methods, however before the change is implemented, there is often a great deal of resistance and fear (Girotti, 2011).

Change is, however, inevitable within veterinary practice; it may come from within the profession, for example changes imposed by the regulatory body, or from external sources such as consumer feedback or increased demand for specialist services. Veterinary nurses are well placed to drive and support change in practice, however such change must be implemented carefully and supported by a solid evidence base in order to achieve desired outcomes for both patients and staff (Mount and Anderson, 2015; Ballantyne, 2018).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.