Critically ill patients will require suitable nutritional support to protect against severe catabolism and to prevent significant deterioration of their condition. Early detection of patients that are malnourished and/or at high nutritional risk is important for timely and optimal nutrition intervention; these typically will be patients suffering from lack of appetite or the ability to eat, which leads to proteolysis and related muscle loss. Insufficient nutrient intake can cause impaired immunity; decreased resistance to infection; decreased wound strength; impaired drug metabolism and increases the risk of complications following surgery (Chan, 2015). Nutritional support should be considered for animals that show recent unintentional weight loss that exceeds 10% of their bodyweight or for those whose oral intake has been or will be interrupted for more than 5 days (less with young patients or smaller species), and those with increased nutrient losses from chronic diarrhoea or vomiting, wounds, renal disease, or burns (Marks, 2010). The goals of nutritional support are to meet the patient's nutritional needs and prevent further deterioration. This can be achieved by offering a high quality food providing adequate energy substrates, essential fatty acids, protein and micronutrients, initiated as early as possible. As with any medical intervention, there are always risk factors to consider which can be minimised by formulating a nutritional strategy including a systematic evaluation of the patient, referred to as a nutritional assessment to develop a specific nutritional plan that meets the individual's needs. Making an accurate estimate of calorie consumption is of great importance in the successful nursing of these critically ill patients.

The importance of nutrition in critical illness

Nutrition is essential for good health, but it is particularly important to critically ill patients. This is because they can quickly develop malnutrition, or pre-existing malnutrition is aggravated as a result of the inflammatory response and metabolic stress associated with illness and injury (Wortinger and Burns, 2015). During a period of simple starvation when an animal is free of disease but does not eat for several days, for example a cat locked in a garage without food, initially maintenance of normal blood glucose concentrations is via glucose and fat stores, with protein stores (found in organs and muscle) tending to be conserved as much as possible. The initial source of metabolically derived glucose is from glycogenolysis: breakdown of glycogen, especially hepatic glycogen which converts to glucose. Protein is then catabolised to provide amino acids, necessary for glucose synthesis. After 48–72 hours, metabolic rate slows and fat stores become the preferential energy source, which acts to prevent further protein breakdown. This system is in place to improve chances of survival by limiting the extent of tissue catabolism (Wortinger and Burns, 2015).

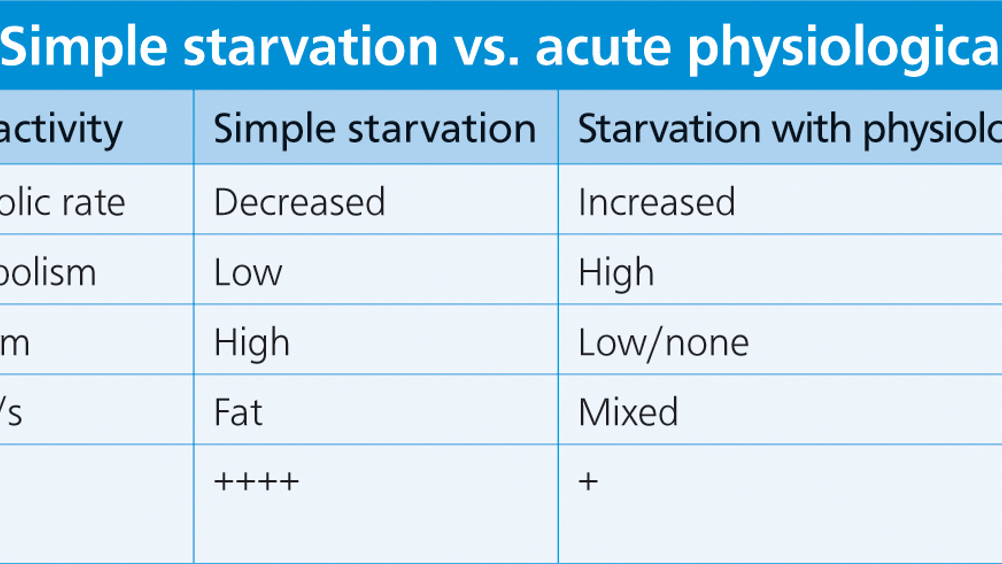

During a period of physiological stress, the response is very different (Table 1). There is a series of changes in hormone levels that alters metabolism in response to tissue injury, infection and inflammation, increasing metabolic rate and causing an increase in energy and nutrient requirements. These hormonal changes mean that during critical illness if the patient is not receiving adequate nutrition the patient will quickly go into a catabolic state, rapidly breaking down the body's stores of nutrients. During illness or injury there is a greatly increased protein demand to provide amino acids for immunoglobulin and acute phase protein production — the two foundations of the immune system. Protein catabolism from visceral and skeletal muscle will be rapidly utilised for energy and production of these acute phase proteins if nutrition is not provided. This catabolism can include and affect all body systems, such as the cardiovascular, respiratory, and immune systems (Chan, 2015). Malnutrition during the hospitalisation period may lead to immunosuppression, increased bacterial translocation with increased risk of sepsis, delayed wound healing, prolonged hospitalisation, compromised organ function and increased morbidity and mortality (Chan, 2015).

Table 1. Simple starvation vs. acute physiological stress

| Metabolic activity | Simple starvation | Starvation with physiological stress |

|---|---|---|

| Basal metabolic rate | Decreased | Increased |

| Protein catabolism | Low | High |

| Fat catabolism | High | Low/none |

| Primary fuel/s | Fat | Mixed |

| Ketone body production | ++++ | + |

The aims of nutritional support are to:

- Prevent further catabolism of lean body mass

- Provide energy and nutrients for healing

- Correct nutritional deficiencies and imbalances.

Meeting nutritional needs and estimating requirements

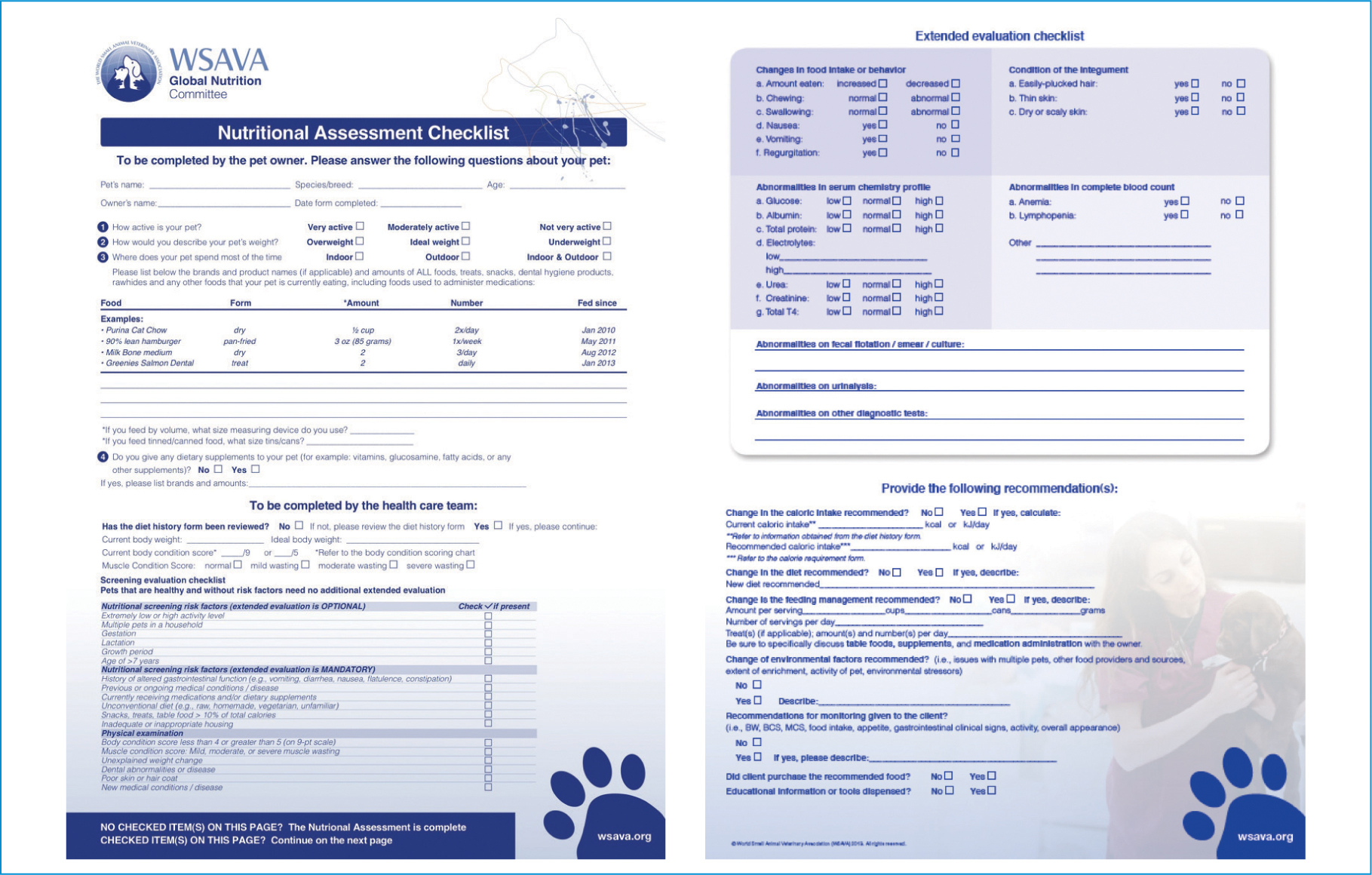

A nutritional assessment must take place as part of each patient's initial examination, including measurement of the patient's weight, body condition score and muscle condition score, in addition to calculating their resting energy requirement (RER). The World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) Nutrition Toolkit has a downloadable Nutritional Assessment Checklist that provides a checklist of nutritional factors and any observed abnormalities (Figure 1). An animal's RER can be defined as an estimation of the amount of the daily energy needed to sustain essential bodily functions while the dog/cat is at rest in a thermoneutral environment. While energy requirement during critical illness will not necessarily increase, key nutritional factors may change. When this nutritional assessment has taken place, a plan is designed with the aim to provide adequate nutrients (energy, protein, essential fatty acids and micronutrients) to meet the daily requirements, minimise abnormal metabolism, minimise protein breakdown, support the immune system and support wound healing (Chan, 2013). A full range of nutrients needs to be provided to patients, but very often when nutritional requirements are discussed it is energy requirement that dominates. While providing too few calories may predispose the patient to malnutrition, it should be noted that overfeeding may cause meta-bolic and gastrointestinal complications, hepatic dysfunction, increased carbon dioxide production, and weakened respiratory muscles (Chan, 2010).

It possible to assess energy requirements of a patient using one of the several RER formulae to calculate the minimum requirements. The most widely accepted formula for calculating RER in cats and dogs weighing between 2 kg and 45 kg is:

RER = (30 x (bodyweight in kg) + 70

For patients that are smaller than 2 kg and larger than 45 kg, the formula changes to:

RER = 70 x (bodyweight in kg)0.75 (Wortinger, 2019).

Historically, the RER value of a hospitalised patients was multiplied by an illness factor (e.g. x2 for full thickness skin burns and cancer), however recent evidence suggests that the illness factor over-estimated the energy requirements causing adverse effects and patient complications, so illness factors are no longer used (Wemple, 2010).

Choosing the right diet and understanding labels

Wherever possible a food-first approach should be used, encouraging patients to voluntarily eat a high quality complete diet; this is considered the ideal method for administering nutrition (Wemple, 2010). The list of ingredients must be arranged in decreasing order by predominance by weight (Food Standards Agency, 2020; AAFCO, 2012). A good quality brand will list their ingredients by their specific name rather than vague descriptions such as ‘meat derivates’, as unfortunately there is no way to determine quality of the ingredients from this list. For example, the diet of critical care patients needs to contain a good quality protein source to ensure the ten essential amino acids (plus taurine in cats) are provided as they are needed for maintenance, healing, production of inflammatory proteins, tissue repair, immune cell function, albumin synthesis and the production of antibodies (Chan, 2015). Animal sources of protein meet these criteria (Michel, 2019) and should be first in the list and therefore the greatest ingredient. Stating the specific source is very useful.

Composition of diets

In the UK pet food manufacturers are required to include minimum percentages for crude protein, crude fat and oils, crude fibre, crude ash (minerals) and maximum percentages of moisture if this exceeds 14% (PFMA, 2015). It should be remembered that the term crude refers to the specific method of measuring the quantity of the nutrient, not to the quality of the nutrient itself.

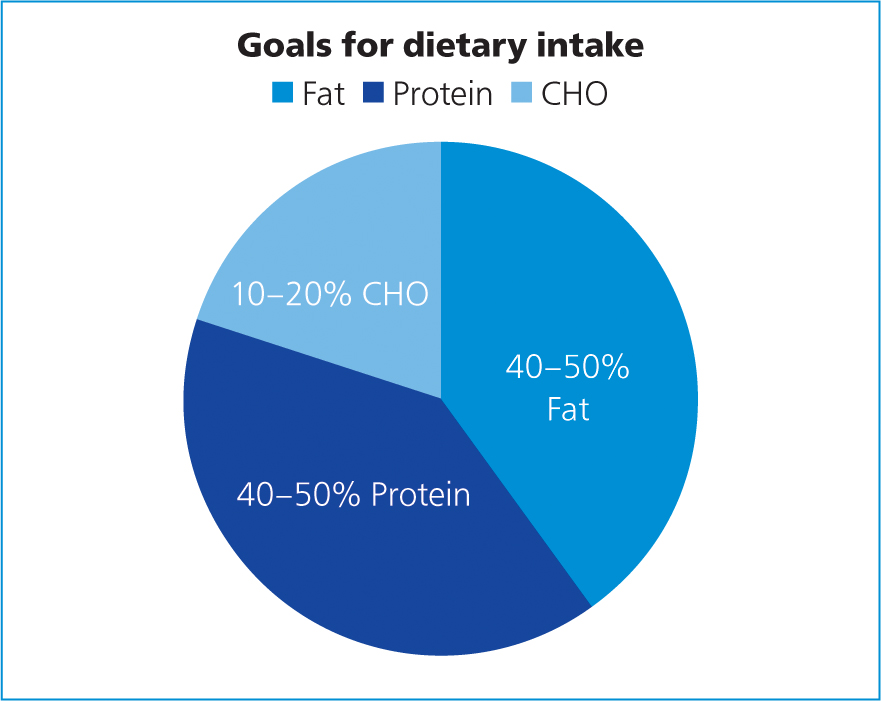

These figures establish the average amount of nutrients in the food; while not being useful in determining the quality of the protein, for example, it can still be valuable information. For example, Marks (2013) suggested 30–50% of the total energy provision for critically ill patients receiving enteral nutrition should be from protein and this is quite easy to determine from the label.

Most of the commercially available foods for debilitated patients provide these levels (Figures 1 and 2, Table 2). It should be noted that protein intake may have to be reduced in patients that cannot tolerate higher levels of protein, such as those with acute and chronic renal failure, azotaemia and hepatic encephalopathy (Chan, 2015).

Table 2. Comparison of some commercially available critical care support diets in the UK

| Feline and Canine Convalescence Support® | Recovery Support® | Hills a/d® | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Royal Canin | Royal Canin | Hill's Pet Foods |

| Energy levels/ml | 1.5 kcal | 1 kcal | 1.2 kcal |

| Protein levels (as percentage of calorific intake) | 36 | 39 | 33 |

| Fat levels (as percentage of calorific intake) | 45 | 55 | 54 |

| Carbohydrate levels (as percentage of calorific intake) | 16 | 6 | 13 |

Fat is a very concentrated source of energy meaning that relatively small volumes can provide a large amount of energy as well as providing essential fatty acids. It is advised that 30–50% of the metabolisable energy of the diet should originate from fats and oils (Marks, 2013) (Figure 3). Wakshlag and Kallfelz (2006) suggested that higher levels of fat in the diet also increase the palatability of diets as does protein. Most commercial ‘recovery diets’ for dogs and cats are approximately 45–57% and 55–68% calories from fat, respectively (Chan, 2015).

It should be noted that these high fat diets are considered contraindicated in patients with fat malabsorptive diseases, pancreatitis, hyperlipidaemia, lymphangiectasia or chylothorax, thus these patients would require preparation of special low-fat formulae (Chan, 2015; Wortinger and Burns, 2015).

It is essential that in addition to having the correct energy and protein requirements, diets are also balanced. At least 25 other essential nutrients, including fatty acids, minerals and vitamins need to be included. They should be supplied daily, particularly those which cannot be stored in the body for any length of time, such as electrolytes, and the water-soluble B vitamins (e.g. niacin, folic acid, thiamine etc.) (Fascetti and Delaney, 2012). Critical care formulae are designed to provide at least the normal adult maintenance requirements for the species.

Note, the percentage of total calories from digestible carbohydrates (CHO) in diets designed for convalescing dogs and cats is typically restricted, this is beneficial for patients that are critically ill as carbohydrates are poorly utilised because of peripheral insulin resistance and could lead to hyperglycaemia, glucosuria, hyperosmolarity, hepatic dysfunction, and respiratory insufficiency (Marks, 2013).

Ultimately the choice of diet depends on several features such as the patient's condition, whether voluntary food intake is possible or whether the diet needs to pass easily through a feeding tube.

Delivery of nutrition

Encouraging the animal to eat voluntarily should always be considered first; however, impaired appetite is a common feature of illness especially in critically ill patients, where many changes occur that can be responsible for a decrease in appetite. These can be psychological, environmental and physiological factors as well as poorly controlled pain and the side-effects of certain medications (Cook, 2018). A significant influence that should be considered is that hospitalised patients often experience substantial amounts of anxiety, which directly affects appetite (Lloyd, 2017). Spending time with the patient, ensuring they are in a calm, stress free environment and providing appropriate care and attention should not be overlooked as this may be enough to encourage voluntary eating in some patients (Cook, 2018) (Table 3).

Table 3. Strategies for encouraging voluntary food intake

| Strategy | Notes |

|---|---|

| Calm, stress free environment | Create a quiet, isolated, comfortable feeding area. Cats will benefit from having a hiding place. Ambulatory dogs may benefit from being fed in a separate area to where they are kennelled |

| Increase palatability of food | Gently warm food to just below body temperature and choose a high fat, high protein diet if suitable |

| Increase moisture | Most patients will prefer canned/wet food |

| Ensure food freshness | Provide fresh food, that has only recently been unpackaged |

| Provide limited food at one time | Providing a selection of foods at one time is not recommended and may lead to food aversions |

| Eliminate physical barriers to eating | Food bowls should be easily accessible and the right shape and size for the patient. Elizabethan collars may be temporarily removed under supervision |

| Avoid appetite-stimulating drugs | Appetite stimulants may be a consideration in some veterinary patients ideally only as a short-term ‘kick-start’ (Michel, 2018), but as with all medications there are possible side effects so careful consideration is needed |

Many patients will prefer being fed moist food with a high protein and fat content; warming the food to just below body temperature and using foods with a strong odour also help to entice the patient (Delaney, 2006). Some may be encouraged to eat by being hand fed small amounts, and in the author's experience this is usually more successful if a member of the team who is not involved in unpleasant responsibilities, such as administering injections etc, takes on the responsibility of feeding (Figure 4).

Enteral feeding

Enteral feeding refers to provision of nutritional support via the alimentary tract or any route connected to the alimentary system, this can be voluntary oral intake or delivery of nutrition via an enteral feeding tube such as a nasogastric tube or an oesophageal tube. Tonozzi (2017) describes how voluntary oral intake should always be considered as the first choice and can be justified on cost alone, but unfortunately, this route rarely results in consistent intake of an adequate quantity of nutrients. Michel (2019) recommended that in many critically ill patients placing a feeding tube to deliver nutrition is the best way to ensure the patient is receiving adequate nutrition.

Conclusion

Critically ill patients are at high risk of malnutrition. By carefully monitoring the patient's intake soon after admittance to the hospital as well as monitoring clinical condition, the RVN can quickly establish those that are likely to be at risk. Although oral feeding should be offered first, many of the patients that are critically ill have very poor appetites, so the use of enteral tube feeding should be considered early on.

There are multiple options for delivery of nutrition to critical care patients so no patient should be left for any significant period without.

KEY POINTS

- Critically ill patients are at high risk of malnutrition because of catabolism and the rapid breakdown of energy and protein stores.

- The catabolic depletion of protein reserves is one of the most marked features of critcally ill patients.

- By providing adequate energy substrates, protein, essential fatty acids and micronutrients, the registered veterinary nurse can support tissue repair, wound healing and improved immune function.

- Oral nutrition should be initiated as early as possible while considering the risks of complications (e.g. aspiration).