The veterinary nurse's role in the management of acute oropharyngeal injury in dogs

Abstract

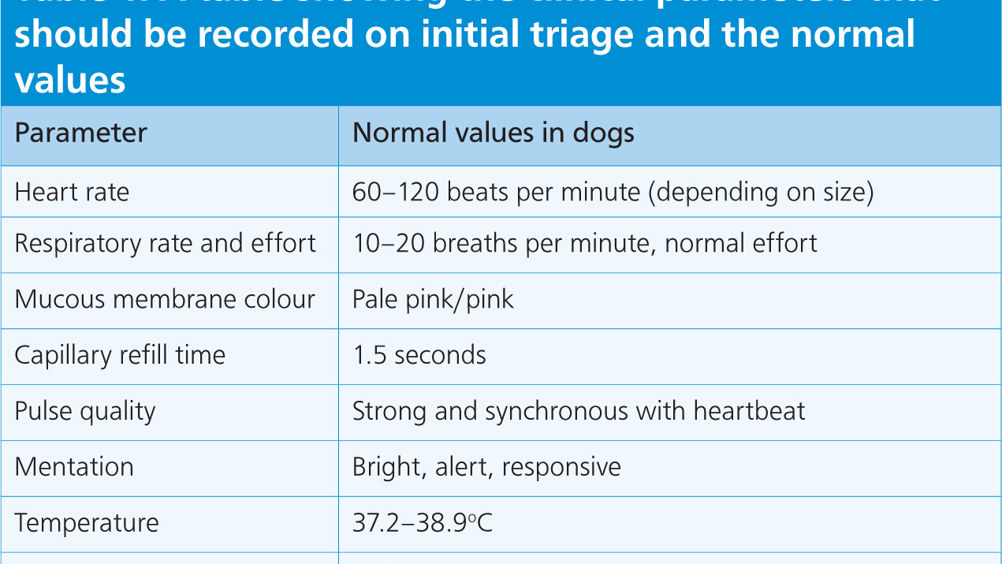

Oropharyngeal injuries are commonly seen in practice. Severity can range from minor the life threatening. It is important that veterinary nurses can confidently perform an initial triage, recognise life-threatening problems, and provide initial stabilisation to these patients. Nurses play a fundamental role in the management of these cases throughout their stay in hospital. This article aims to provide practical advice and guidance on cases of oropharyngeal injury, and the importance of client education to help prevent similar cases in the future.

Acute oropharyngeal puncture wounds are relatively uncommon in general practice but are potentially life-threatening events if not recognised promptly (Griffiths et al, 2000). In cats and dogs, they can be caused by a variety of foreign bodies such as wood, metal, bones, sewing needles and fishhooks (White and Lane, 1988; Griffiths et al, 2000). In dogs, the most common presentation is associated with carrying, chewing, or retrieving wooden sticks (Hallstrom, 1970; White and Lane, 1988; Doran et al, 2008; Anderson, 2017).

Two presentations of oropharyngeal injury are typically seen clinically; the acute and chronic stages (Griffiths, et al, 2000; Doran et al, 2008). Acute injury is defined as cases that present within 7 days of the traumatic event, whereas chronic cases are those presenting after this time (Baker, 1972; White and Lane, 1988). This article aims to provide practical advice and guidance to veterinary nurses managing cases with acute oropharyngeal disease.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.