A patient care report of a Doberman in heart failure

Abstract

This article describes the nursing care provided to a Doberman in acute life-threatening heart failure due to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). DCM is a common problem seen in medium-large breed dogs. It can sometimes lead to congestive heart failure (CHF) and cause arrhythmias, further compromising cardiac function. Nursing care, monitoring and therapy are vital for the patient both in the short term, but also long term, to optimize quality of life.

Signalment:

Species: Canine

Breed: Doberman

Age: 7 years

Sex: Male (neutered)

Weight: 43.3 kg

Henry was presented with acute onset respiratory distress. He had a 2 month history of exercise intolerance and breathlessness, but had developed a retching cough 4 days prior to presentation, and had experienced one syncopal episode.

On presentation, the patient had a frail, quiet but alert demeanour. He had audible crackles over his lung fields, a respiration rate (RR) of 40 breaths/minute with increased respiratory effort (RE), and a cough. He had a grade 2/6 left-sided, apical, systolic heart murmur and weak peripheral pulses. His heart rate was 140 beats/minute, with no pulse deficits. Temperature was 38.2°C.

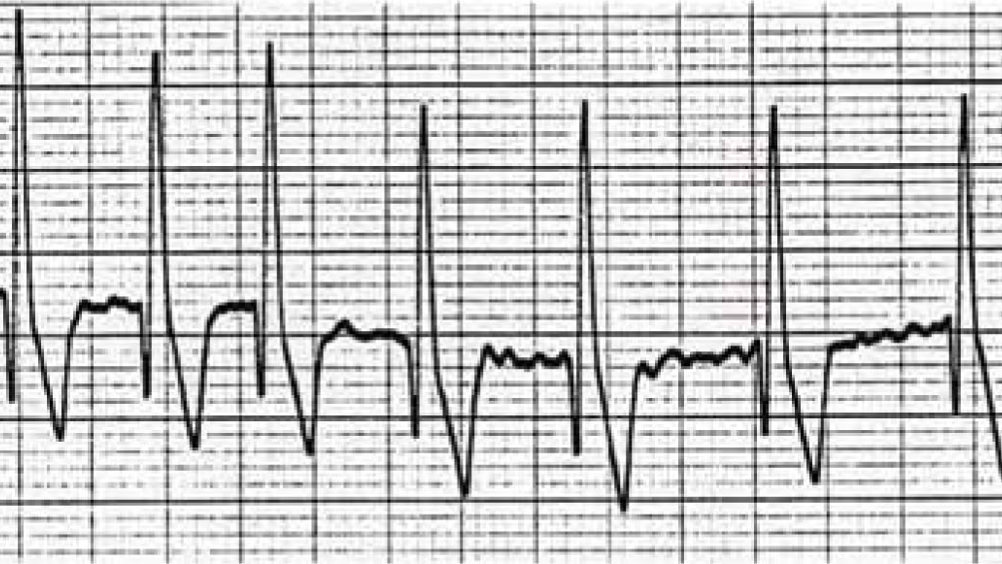

An intravenous (IV) catheter was placed in a cephalic vein, and blood was taken for haematology and biochemistry from the catheter. A mild hyperkalaemia (4.78 mmol/l), and mild hyperglycaemia (6.78 mmol/l) were the only abnormalities found. On the basis of his history and physical examination, congestive heart failure (CHF) was suspected. The veterinary surgeon instructed IV furosemide (2 mg/kg) to be given, and the patient was settled into a kennel with supplemental oxygen provided by nasal prongs. A continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) recorded a sinus rhythm with an average heart rate of 150 beats/minute. He was allowed to adjust to his new surroundings before further diagnostic tests were performed.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.