References

A retrospective survey evaluating the prescribing tendencies of UK veterinary surgeons, relating to the use of anti-inflammatory drugs in canine angiostrongylosis

Abstract

Background:

In addition to anti-parasitic therapy, appropriate supportive care is vital for the successful treatment of canine angiostrongylosis.

Aim:

This study sought to determine the prevalence and reasons for the use of corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), by veterinarians, as a supportive treatment for canine angiostrongylosis. Specifically, the study investigated the use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of inflammation, anaphylaxis and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, which can develop in some dogs infected by

Methods:

These aims were achieved by surveying UK veterinarians from a non-endemic area, Yorkshire, and an endemic area, South East England, for canine angiostrongylosis. Responses were received from independent, corporate-owned and referral practices.

Results:

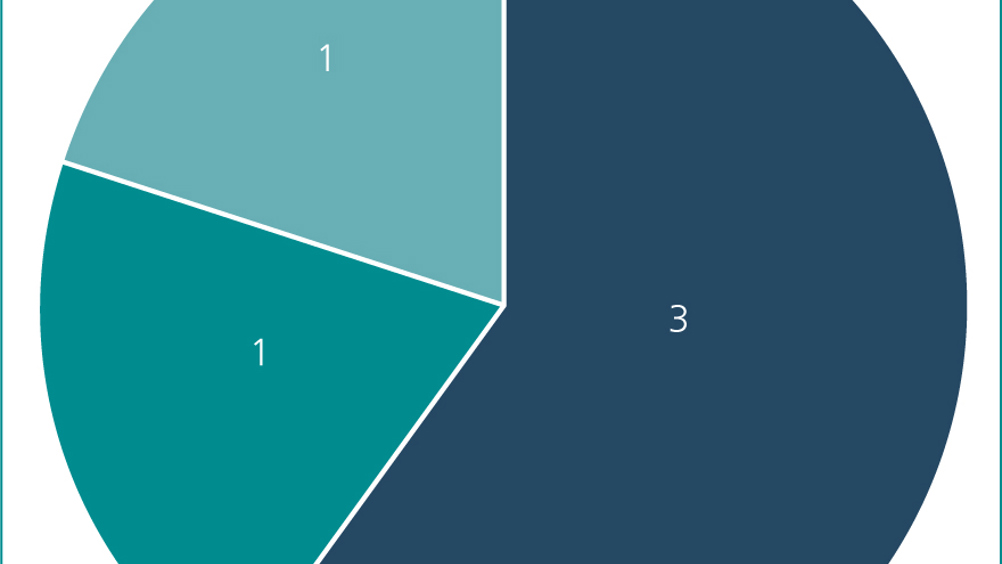

Overall, more veterinarians would administer corticosteroids (80%) compared with NSAIDs (40%). Most respondents surveyed stated administration would be case dependent, including the severity of perceived inflammation. Four of six veterinarians who would never administer NSAIDs cited coagulopathies as the reason for their decision-making. While the regional comparison here revealed no significant differences, wider sampling may produce identifiable trends.

Conclusion:

The survey responses revealed a lack of understanding of if, when, and why, anti-inflammatories should be administered. Imperatively, further research is needed to address this lacuna.

Angiostrongylus vasorum is a metastrongyloid nematode with a complex indirect lifecycle. The adult L5 stage of A. vasorum resides and deposits its eggs in the right side of the heart and pulmonary arteries of dogs that act as the definitive host (Ridyard, 2005; Morgan and Shaw, 2010). The eggs hatch to first-stage larvae (L1), which penetrate the alveoli, migrate up to the oropharynx, after which they are swallowed and then excreted in the faeces. The L1s are ingested by an intermediate host, commonly snails and slugs (Helm et al, 2010), however, there is also evidence of the common frog (Rana temporaria) acting as a paratenic host (Bolt et al, 1993). The dog ingests the intermediate or paratenic host containing infective third-stage larvae (L3). L3s cross the intestinal wall and migrate to the abdominal lymph nodes, where they moult to fourth-stage larvae (L4); then enter the portal circulation, migrate via liver parenchyma and ultimately reach the right ventricle and pulmonary arteries, where they mature to the adult L5 stage. A. vasorum deposits of immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG, IgM), complement (C3), and fibrinogen have been reported in the lungs of infected dogs during the acute phase of infection (~1–2 months post-infection). Wild canids, such as red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) can be infected and serve as reservoir hosts (Sreter et al, 2003). A. vasorum has also been reported in wolves (Canis lupus), coyotes (Canis latrans), jackals (Canis aureus), and other wild canid species (Elsheikha et al, 2014).

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting The Veterinary Nurse and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.