The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP, 2016) defined pain as ‘an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’. This should not be confused with nociception which refers purely to the sensory or physiological process involved in a painful experience, whereas pain relates to the overall experience and how the animal feels as a result. The perception of pain in animals is very difficult to quantify as it is a combination of the integration of nociceptor information with many other central nervous system (CNS) and body inputs into the cerebral cortex.

Nociception, the physiological component of pain, consists of three processes, which are transduction, transmission and modulation, and involves pain receptors, nociceptors, and nerve fibres in the periphery, spinal cord and brain:

The final step in the overall pain pathway is perception, which is the integration of the nociceptor information provided to the cerebral cortex with other information from learned experiences or memories resulting in the conscious, subjective and emotional experience of pain. Having a clear understanding of the pathophysiology of the pain pathway is vital if an informed approach to pain management and the use of analgesic drugs and hence pharmacological modulation is to be achieved.

When considering a dental patient, veterinary practitioners must be aware that the patient may have existing chronic pain, for example from an abscess, and may experience acute pain as a result of the procedure undertaken, or a combination of the two. Acute pain, if not detected early or managed well, can cause peripheral neural wind-up, which then makes pain harder to control and manage in patients, even promoting the development of chronic pain (Clark, 2010). Neurogenic inflammation causes the release of various substances from the nerve endings, such as serotonin, histamine, acetylcholine and bradykinin, which serve to activate and sensitise other nociceptors; this is primary hyperalgesia. This, combined with the effects of prostaglandins from damaged tissues, enhances the nociceptive response to inflammation, thus lowering the patient's threshold to noxious stimulus (Hudspith et al, 2012). Preventing and controlling pain should be central to veterinary medicine (Benson, 2000) and by understanding the mechanisms associated with pain veterinary professionals can anticipate how it might occur, when it might occur, how it might progress, and thus plan to ideally prevent it or manage it well (Hellyer et al, 2007).

It is the role of the veterinary nurse to be able to pain score all patients, including those admitted for dental, oral and maxillofacial surgeries, in order to identify and quantify pain, and to assess the efficacy of analgesic interventions. There are pain score systems available for use in veterinary practice, however with regards to oral pain the veterinary nurse should also be mindful of signs such as poor coat condition due to a lack of grooming, difficulty when eating both with prehension and mastication, and any alteration to the patient's demeanour that could be indicative of pain.

Pre-emptive analgesia

Pre-emptive analgesia is analgesia given before the pain response is triggered with the aim of avoiding ‘wind up’, the development of peripheral and central sensitisation (Lantz, 2003). Stimulation of the pain pathway results in sensitisation which results in a more vigorous response to further noxious stimuli or even to previously innocuous stimuli, causing the animal to experience relatively more pain. Pain is much more difficult to manage if sensitisation has occurred, which in turn means that far higher doses of anal-gesic drugs are required to dampen down the pain pathways and produce adequate levels of pain relief. In some cases this might not even be achievable.

If the initial stimulation of the pain pathway can be reduced then less sensitisation will occur and the resulting pain will be much easier to control. This can be achieved by administering the analgesic drugs before any pain is experienced, so pre-emptively. When tissue damage does occur the pain pathway is already blocked so does not fire to the same extent, producing less sensitisation, which results in the ensuing pain being easier to control.

Obviously the commonest situation when this can be applied is prior to surgery as there is massive stimulation and firing of the pain pathway when tissues are traumatised by the surgical procedure. Once the animal recovers from the anaesthetic it will be bombarded with pain signals and massive sensitisation will occur if analgesia has not been provided; the animal will be in intense pain and discomfort. It would therefore seem logical to give analgesics pre-operatively to reduce the initial stimulation of the pain pathway during surgery and minimise the development of sensitisation and hence postoperative pain.

Multimodal analgesia

Multimodal analgesia involves combining two or more analgesic drugs of different types to achieve an additive or synergistic effect; an opioid and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), for example, or an opioid and a local anaesthetic. It involves using different classes of analgesics in combination to block the pain pathways at different levels. It is thought that this approach is more effective than using a single analgesic because as the pain pathway is so complex and involves many different neural mechanisms, neuro-transmitters and receptors it is unlikely that one analgesic alone would be able to block all the possible permutations and produce effective pain relief (Lamont, 2008).

Pharmacological pain management

Hughes (2008) indicated that there are many different analgesic drugs available for use in veterinary practice including NSAIDs, local anaesthetics and opioids, of which the latter tends to be most widely used. Multimodal and pre-emptive analgesic regimens should be devised, implemented and monitored carefully for all dental patients, and the variety of drugs and therapies available for use in practice can interrupt the pain pathway at different stages:

In addition to NSAIDs, local anaesthetics and opioids there are other drugs which have useful analgesic properties for patients, including:

Pain management in dental patients

All patients undergoing dental procedures should receive a pre-medication which contains an analgesic drug. The choice of drug lies with the veterinary surgeon once they have clinically and physically assessed the patient, bearing in mind the extent of the proposed surgery. The common choices include buprenorphine, a partial agonist, or metha-done, a pure agonist, which is typically administered with a sedative, such as acepromazine, to create a neuroleptanalgesic combination. This will help block the pain pathways centrally. The veterinary surgeon will also choose to administer a NSAID drug to block the pain pathways in the peripheral tissues, and the decision regarding which NSAID to give and when to administer it will depend on the individual animal and their health status. The consequences of poorly managed pain include poor wound healing, a suppressed immune system, anorexia or inappetance and associated complications such as weight loss, depression and behavioural changes, to name a few.

Local anaesthetic drugs

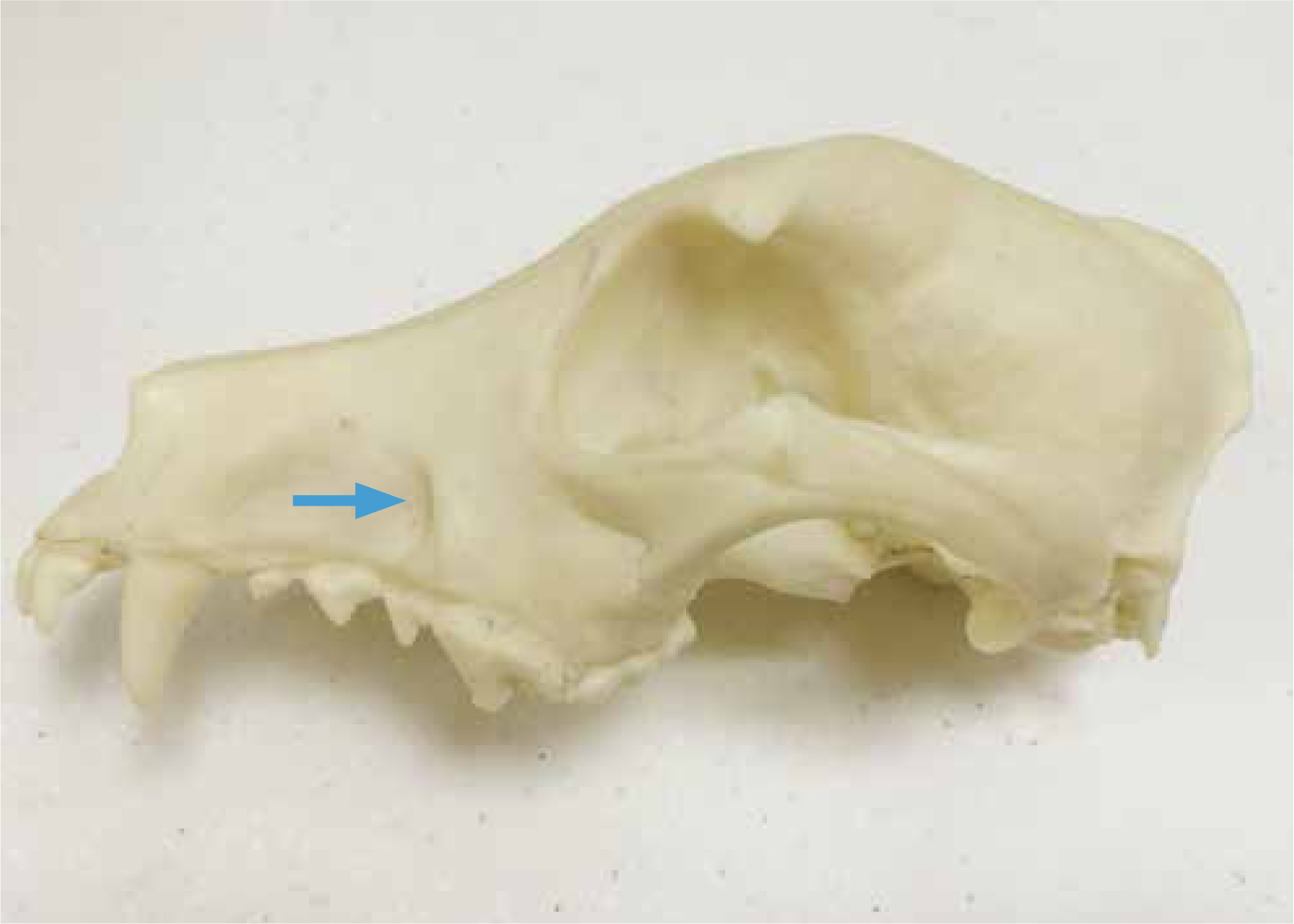

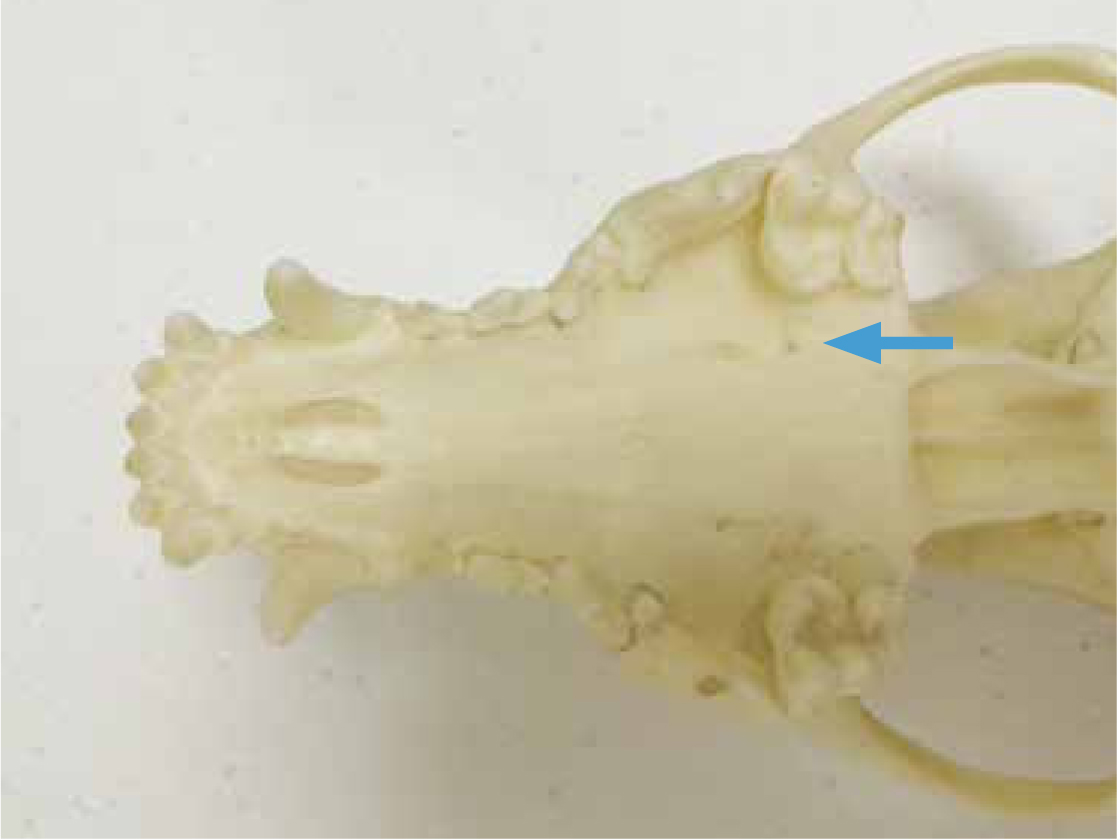

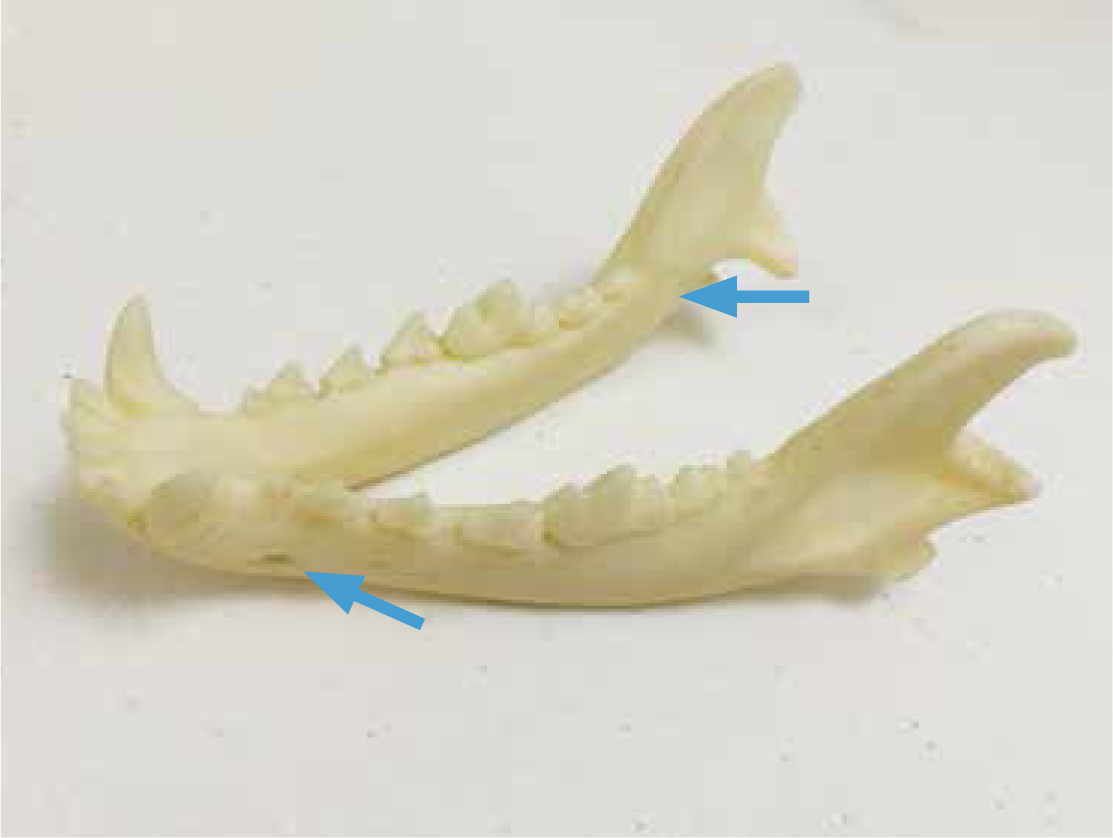

In relation to dental surgery patients, veterinary practitioners must be knowledgeable regarding the nervous supply to all tissues including the teeth, soft and hard oral cavity tissues, all of which may be manipulated depending on the treatment the patient requires. The use of local anaesthetics to block nervous impulse transmission is considered gold standard for any dental patient and should be considered in all circumstances. O'Dwyer (2015) expressed that they are relatively simple to perform, do not cost very much and work quickly, which is beneficial when a patient is under anaesthesia in order to reduce anaesthetic time. There are nerves supplying the teeth, soft and hard tissues originating from the trigeminal and facial cranial nerves, which run through the mandibular canal and exit through the mental foramina, in addition to those emerging from the mandibular, infraorbital and palatine foramen (Figures1, 2 and 3). They supply all of the tissues that are going to be incised, burred, elevated, sutured, and manipulated throughout any dental procedure.

There are a number of different local an-aesthetics to use for this purpose, and the choice lies with the veterinary surgeon who will consider their onset and duration of action. Some examples of these drugs include lidocaine, mepivacaine, bupivacaine and articaine, and the veterinary surgeon should consult the relevant texts and data sheets regarding perineural administration doses and contraindications. These drugs can be purchased in ampoules (Figure 4) and administered using a dental syringe (Figure 5) and specific needles, which are typically 27 or 30 gauge (Figure 6). Short and long varieties of these needles can be purchased to ensure the veterinary surgeon can reach to where the drug needs to be injected.

The veterinary surgeon must be mindful that the main neurovascular bundles running in the aforementioned canals and exiting those foramen primarily supply the inside of the tooth, so the pulp. Therefore, blocking these nerve branches with drugs will effectively ‘knock out’ all of the pulps in any given area, but they must also consider the soft and hard tissues. This is why, in addition to the nerve blocks, it is advisable to infiltrate the surrounding tissues as well. For example, if the upper left canine tooth is to be surgically extracted, it involves incising gingiva, lifting the periosteum from the bone to create a flap, removing a proportion of the bone over the root to create a window over and gutters down the sides of the root, and then using instruments to loosen the tooth and elevate it from the socket. Local anaesthetic should be administered as follows to block all pain signals that will result from this degree of tissue manipulation and insult:

Having done this, in addition to the premedication and potential NSAID administration, the patient should be well analgesed at all stages of the pain pathway, and from a dental perspective the pulp, hard tissues and soft tissues have all been desensitised. This reduces the amount of volatile anaesthetic agent required to maintain anaesthesia in most patients, makes them much more comfortable on recovery, and prevents the wind-up effect, thus promoting better and faster healing.

Surgical technique and instrumentation

All veterinary professionals involved in dental and oral surgeries/interventions must treat all of the tissues gently, adopting Halstead's surgical principles. Spending a little time formulating a treatment plan will enable the veterinary surgeon to appreciate the extent to which the tissues are going to be disrupted and the ways in which they might approach the surgery required. Using the correct surgical technique will promote effective haemostasis, preserve blood supply to tissues and ultimately encourage rapid healing. For this to occur the veterinary surgeon must be proficient at performing the required treatments, but must also have appropriate and well-maintained equipment available, which they know how to use correctly (Holmstrom et al, 2013).

It is advised that air-driven dental units and the hand pieces are properly maintained, a full sterile surgical kit is available for all procedures, there is a good light source, and that luxators and elevators are in good condition and are regularly sharpened. Poor quality, damaged or inappropriately used equipment will inevitably lead to frustrations during procedures and potentially unnecessary tissue damage, all of which will cause, contribute to or exacerbate pain. This could affect healing, but could also impact on other aspects of an animal's daily living such as the ability to rest, groom, eat and drink.

Conclusion

Dental and oral surgeries involve manipulation of hard and soft tissues to varying degrees, and as with any other procedures this involves insult and injury to these tissues no matter how good a veterinary surgeon's technique might be. Tissue manipulation will always elicit a pain response, therefore all veterinary professionals must be mindful of this and create an individual analgesia plan for all patients. This plan should ensure the patient receives pre-emptive, multimodal analgesia which blocks the pain pathway at as many points as possible. It is important for veterinary professionals to consider the use of local anaesthetics as a major part of their plan as this is an excellent way to manage pain in dental and oral surgery patients. There are numerous articles, books and training courses available for veterinary professionals to access if advice and guidance is required before these techniques are confidently and safely utilised.