A care bundle is a set of evidence-based interventions that when performed together can significantly improve a patient's outcome (McCarron, 2011). Peripheral intravenous catheters (PVC) are widely used in veterinary hospitals for the treatment of patients; yet there is little information on their management and documentation in general practice. PVCs are used to administer medication directly into the venous system for rapid distribution to the whole body, and also to deliver fluid therapy and nutritional support to the patient. Although intravenous catheter insertion is common practice, it alters the host's defences against infection, which increases the risk of local infection or bacteraemia with more serious complications such as septicaemia (Zias, 2010). This causes concern for patient safety.

Studies have been carried out in human medicine to see if introducing interventions such as removing unnecessary catheters (Pronovost et al, 2006) and staff education (Peredo et al, 2010) can reduce the number of catheter-related infections and complications. In human medicine catheter-related bloodstream infections have been successfully reduced by using a central venous catheter care bundle (Kim et al, 2011).

By implementing a care bundle into the veterinary practice for the management of PVCs it may be possible to reduce the incidence of PVC-related infection and improve patient safety.

Literature review

Catheter-associated infections are a significant and serious problem in human medicine (Weese, 2011). In human nursing, care bundles have been introduced to try and reduce the number of blood stream infections associated with intravenous catheter use (Boyd et al, 2011). A care bundle is a structured way of improving the nursing care of a patient using a set of evidence-based practices that when performed together have been proven to improve patient outcome (Fulbrook and Mooney, 2003).

Anecdotal evidence and personal experience suggests that there is a need for improved documentation of peripheral intravenous catheter care in veterinary medicine. The introduction of a catheter care bundle into veterinary practice may improve patient care and reduce risks associated with the use of intravenous catheters.

Infection control

Seguela and Pages (2011) conducted a study to determine the prevalence of intravenous catheter colonisation in cats and dogs in a routine clinical setting. They studied 100 peripherally placed intravenous catheters. The distal two-thirds of the catheter were removed and submitted for bacterial and fungal cultures. They found that approximately 15% of the hospitalised animals had positive microbial catheter colonisation, where the Staphylococci species were most commonly found. This study supports Weese's 2011 opinion that more thorough hand hygiene measures, disinfection of the hub before injection and a rigorous skin preparation technique could have reduced incidences of microbial catheter-related colonisation. However a limitation of this study is that it was only carried out in one hospital, which means it is not representative of the veterinary population as a whole, so the discovery of Staphylococci species may only be a problem in this hospital. There was also a low sample size of patients which could have limited the results.

PVC care bundles

The PVC care bundle has been implemented into human hospitals and modified to suit the needs of individual institutions. To try and reduce the number of infections and to improve the management of PVCs a care bundle was introduced into a hospital in Dundee. Boyd et al (2011) carried out a 6 month pilot study from September 2007 to March 2008 with the aim to introduce a care bundle that would improve the management of PVCs and reduce the number of PVC-related infections. They also audited the compliance of the staff involved over a 25 week period to assess sustainability of the care bundle. The team agreed on quality indicators for their care bundle using drafts developed by Health Protection Scotland (PVC care bundle) in 2007. The indicators they chose allowed for objective assessment.

Over the 6 months 100 PVCs were audited which equalled a maximum of five patients a week. The PVC study reached its overall aim by constructing a care bundle to improve the management of PVCs and they also calculated the overall compliance of staff carrying out the care bundle was 82% (Boyd et al, 2011).

Bruno et al (2011) used the framework of their study conducted and introduced a PVC care bundle into a hospital in Ireland to see if they could reduce the incidence of PVC-related Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. They altered the care bundle slightly so that it addressed issues relating to whether the PVC was still in use, the presence of any inflammation around the insertion site, whether the dressing was intact, hand hygiene and whether the PVC was in situ for less than 72 hours. They audited the percentage compliance on a regular basis and found that it varied with an average score of 81% over 6 months. A significant reduction in the rate of PVC-related S. aureus bacteraemia in the hospital was also found.

Conclusions from the literature review

From reviewing the literature it is apparent that care bundles could be used to reduce catheter-related infections and improve human patient safety. It is evident from the studies that have been carried out that implementing interventions such as thorough hand hygiene, aseptic skin preparation techniques and sterile handling of the catheter reduce the rate of hospital-acquired infections associated with intravenous catheters. Care bundles are simple to produce and implement and could be tailored to suit most environments and diagnoses (Aboelela et al, 2007).

At this moment in time there is minimal evidence-based practice for the care of PVCs in the veterinary hospital, however a care bundle could be constructed using the method described in human medicine and tailored to suit veterinary practice.

The aim of this study was to introduce a PVC care bundle as a tool to improve the management of PVCs and patient safety, and to audit staff compliance over a 9 week period, with the long-term goal being to implement the PVC bundle in other veterinary practices.

Materials and methods

This study was carried out at Abbey House Veterinary Hospital, Leeds between November 2011 and January 2012. This is a modern and well-equipped hospital (RCVS Small Animal Accredited Hospital), which also provides an out of hours emergency service. It was considered the ideal site to pilot the PVC care bundle, as it is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year and it is a busy practice with a large number of inpatients. It also has a dedicated team that is highly motivated to provide the best care for their patients. The hospital team consisted of veterinary surgeons some with specialist qualifications, qualified veterinary nurses and student veterinary nurses. One main team leader was chosen from the nursing team who had the responsibility to actively encourage staff participation.

The author and the team agreed on a PVC ‘bundle’ based on a study carried out by Boyd et al (2011). It consisted of 14 quality indicators repeated every 24 hours over a 72 hour period which allowed for objective assessment of clinical performance for insertion and management of the peripheral intravenous catheters (Table 1).

| Patient details |

| Date and time of insertion |

| Location of peripheral catheter |

| Catheter gauge |

| Reason for catheter |

| Appropriate hand hygiene followed before handling patient |

| Appearance of protective bandage layer |

| Any patient interference? |

| Appearance of catheter site and limb |

| Catheter flushed with sterile saline/heparin solution? |

| Injection port cleaned with surgical spirit? |

| Daily review of necessity? |

| Catheter removed? And reason |

The PVC ‘bundle’ was organised into a table format agreed with the team to try and keep data collection simple (Table 2). This was repeated at 24 hours, 48 hours and 72 hours.

| Day | Catheter care procedure | ✓ or ✗ | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient details: species, breed | |||

| Date of insertion | |||

| Time of insertion | |||

| Location of peripheral catheter (e.g. left cephalic vein) | |||

| Catheter gauge | |||

| Reason for catheter (e.g. GA, IVFT, chemotherapy) | |||

| +24 hours | Appropriate hand hygiene followed before handling patient:

|

||

| Appearance of protective bandage layer

|

|||

| Any patient interference, chewed? | |||

| Appearance of catheter site and limb

|

|||

| Catheter flushed with sterile saline/heparin solution? | |||

| Injection port cleaned with surgical spirit? (if applicable) | |||

| Daily review of necessity? Does the patient still need the catheter? | |||

| Catheter removed? Reason for removal |

The ‘bundle’ was assigned to all patients that came into the practice that required a peripheral intravenous catheter as part of their treatment. The members of the team were asked to complete the interventions for each patient who had an intravenous catheter in situ longer than 24 hours and record this on the table provided. Quantitative data were collected once weekly by the author.

Patient and staff identifiers were not used and data were collected following approval from the Royal Veterinary College Ethics and Welfare Committee. All members of staff were asked to sign a consent form before the start of the study.

Results

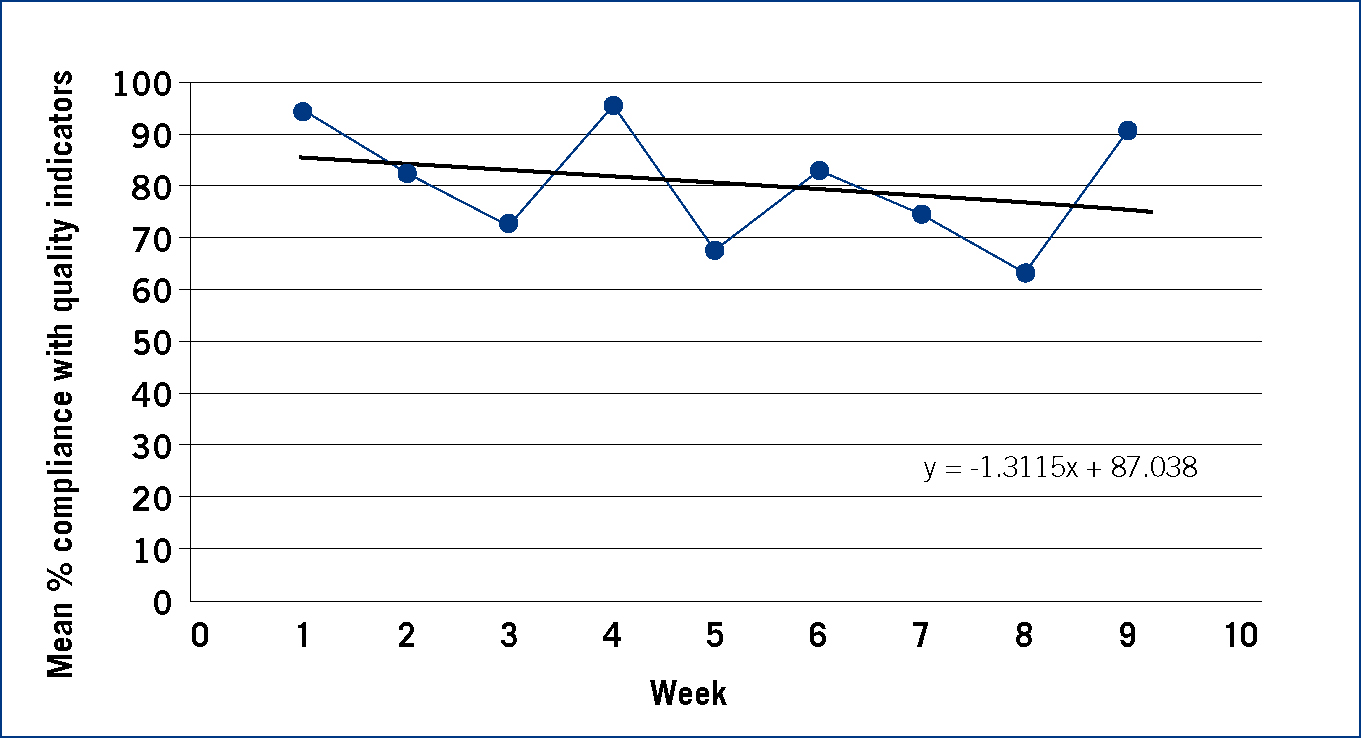

Data for 49 PVCs were analysed over a 9 week period. There was 686 opportunities (49 patients x 14 quality indicators) for possible interventions (quality indicators) to be completed. The mean total compliance was 80.5%, with variation noted week by week (Figure 1) which ranged from 95% in week 4 to 63% in week 8.

There was an overall decline in compliance with the PVC bundle (Figure 1). Over the 9 week period there was an overall decline in compliance of 3% from an initial compliance of 94%. The precision of the study was calculated by using the standard error value of 1.52%/week.

Regression analysis was carried out on each intervention to see if the results were statistically significant. A p value of ≤0.05 was set to donate statistical significance.

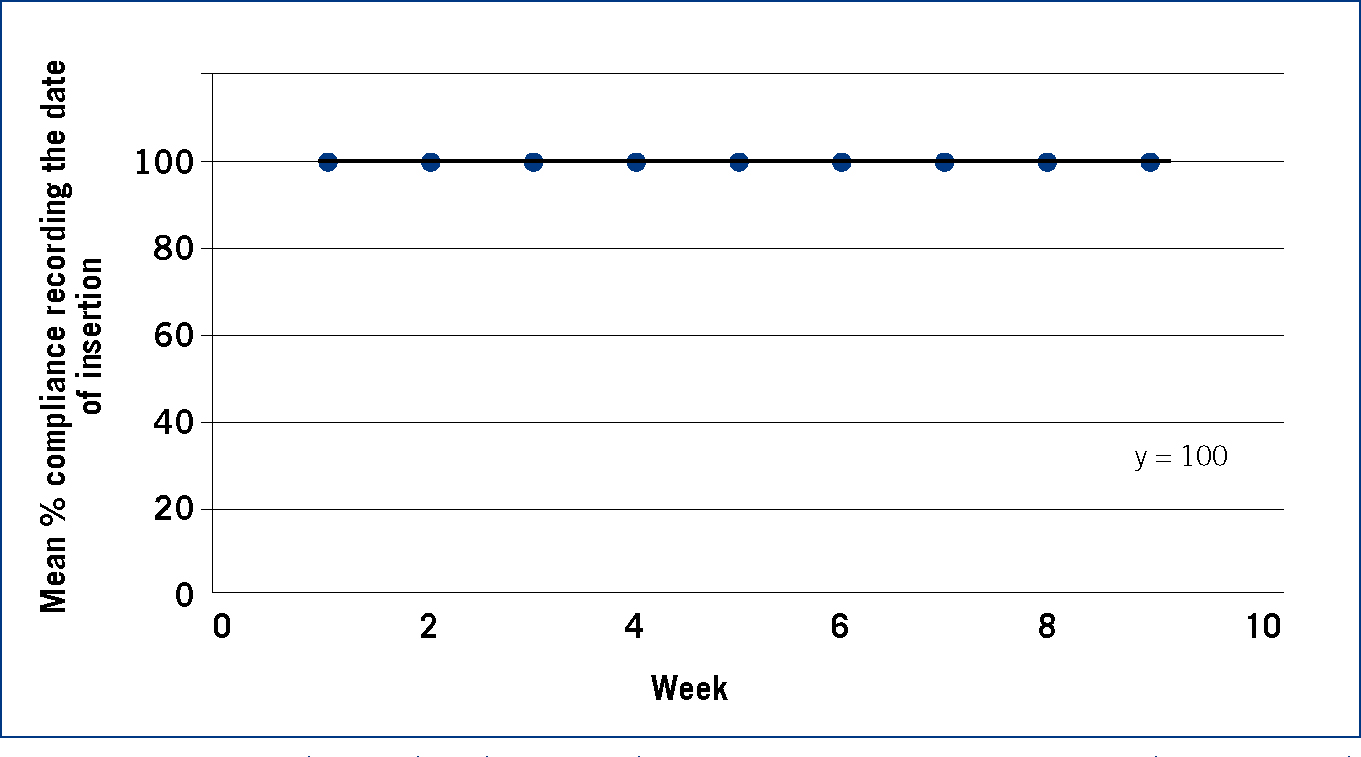

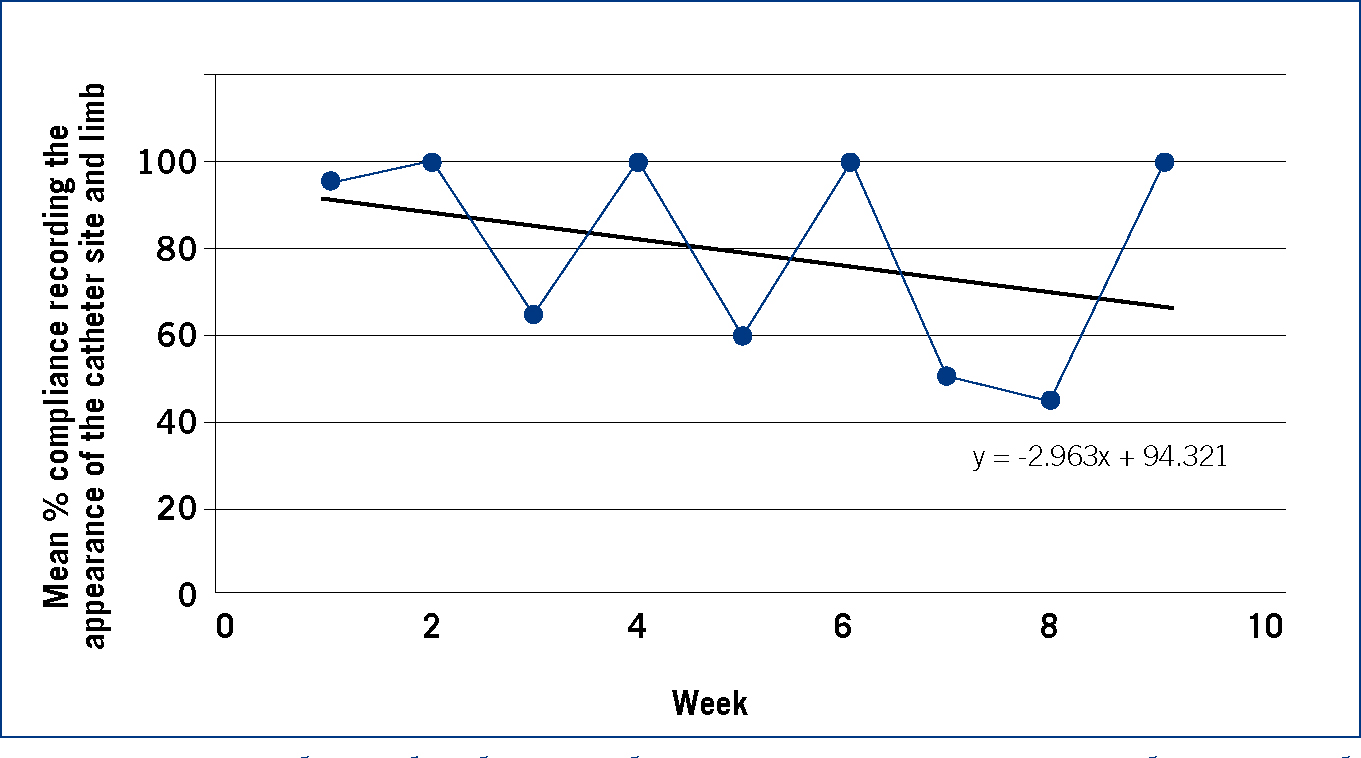

Data for each individual intervention (quality indicator) were also analysed over a 9 week period. Recording date and time of insertion remained at an average of 100% over the 9 week period (Figure 2), and there were improvements over the 9 week period for checking the insertion site and limb (Figure 3) however there was a low mean percentage compliance for recording when the PVC was removed.

Discussion

Care bundles have not yet been introduced into veterinary practice as a way of delivering evidence-based patient care. A care bundle is defined as a collection of processes needed to effectively and safely care for patients undergoing particular treatments with inherent risks. Several interventions are ‘bundled’ together and when combined can significantly improve patient care outcomes (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2006). This 9 week pilot study was designed to measure the percentage compliance of the overall PVC bundle and the individual quality indicators in a veterinary hospital. This allowed for data to be extracted enabling the author to see which quality indicators were not being met. The author believes that using these preliminary results, to target interventions that were not being continuously met would help increase the percentage compliance of the overall bundle. This may lead to a more successful implementation with the likely outcome of increased patient safety and improved PVC care.

Over the study period 49 PVCs were audited. Due to a limited time scale, data were collected from the weekly population of patients to try and increase the sample size resulting in a more accurate calculation of compliance.

The results show that there was an overall decline of 3% for completion of the whole bundle over the 9 week study period. This result is similar to a study published by Morse and McDonald (2009). They conducted a study to see if an intervention such as placing educational posters around the hospital ward would help remind and encourage staff to document the date and time of insertion of PVCs. They collected data before and after the poster placement and found that the percentage of staff documenting the information was low even after the posters were implemented. The posters had little effect on improving the percentage compliance. The author believes that decline in the percentage compliance of the entire bundle could be due to: lack of involvement from entire team, small study period, locum staff and insufficient feedback from researcher. These are likely to be the most significant reasons because if all the team are not involved then the care bundles will not be completed fully resulting in a loss of data. A small study period means that there is less time to collect a sufficient amount of data to analyse.

Weekend shifts and sickness at the hospital were covered by locum veterinary nurses. This variable had not been considered in the planning of the project. Locum nurses were not aware of the PVC care bundle in the hospital. This may have reduced compliance as the care bundle sheets were not always being completed at the weekend. Calculations on the week day sheets only could be done to see if the lack of data collection at the weekend had a significant effect on the overall results. To overcome this issue, all members of staff including locum nurses and locum veterinary surgeons should be made aware of the new process for monitoring PVCs this may help with infection control as all members of staff will be following the same procedure.

Success of the PVC care bundle depends highly on teamwork. Teamwork is proposed as a process involving two or more healthcare professionals with complementary backgrounds and skills, sharing common health goals and exercising concerted physical and mental effort in assessing, planning, or evaluating patient care. This is accomplished through interdependent collaboration, open communication and shared decision making (Xyrichis, 2008). Measuring the percentage compliance with the care bundlehelped to evaluate teamwork, as the result was dependent on the concept of teamwork.

This research suggests that the main barrier for completion of the bundle is staff behaviour. One way to overcome this may be to educate staff on the benefits of the PVC care bundle and how it can improve patient safety. Regular staff meetings with feedback on how the bundle is making a difference may make staff feel more involved and motivated to improve patient safety.

The results show that there was not 100% compliance of the PVC care bundle in this veterinary hospital however this does not mean that it would not work in other hospitals, if improvements were made to the bundle. The PVC care bundle should not be dismissed as its aim is to improve patient safety.

Possible future study

After this pilot study was carried out, amendments were made to the care bundle. It now includes extra interventions such as ease of insertion of PVC and methods used for catheter site preparation (Hancill and RCVS Charitable Trust, 2012). Using this version further research could be carried out to collect data on the veterinary population instead of one practice. These data would give a better indication of whether the care bundle could work and make a difference in practice.

Conclusion

The current study shows that teamwork and staff behaviour highly affects successful implementation of a PVC care bundle. However with more research and education, care bundles have the potential to improve the care of PVCs and improve patient safety; this development should be embraced by the nursing profession.